Doris Day dies; legendary actress and singer was 97

Legendary actress and singer Doris Day has died at 97.

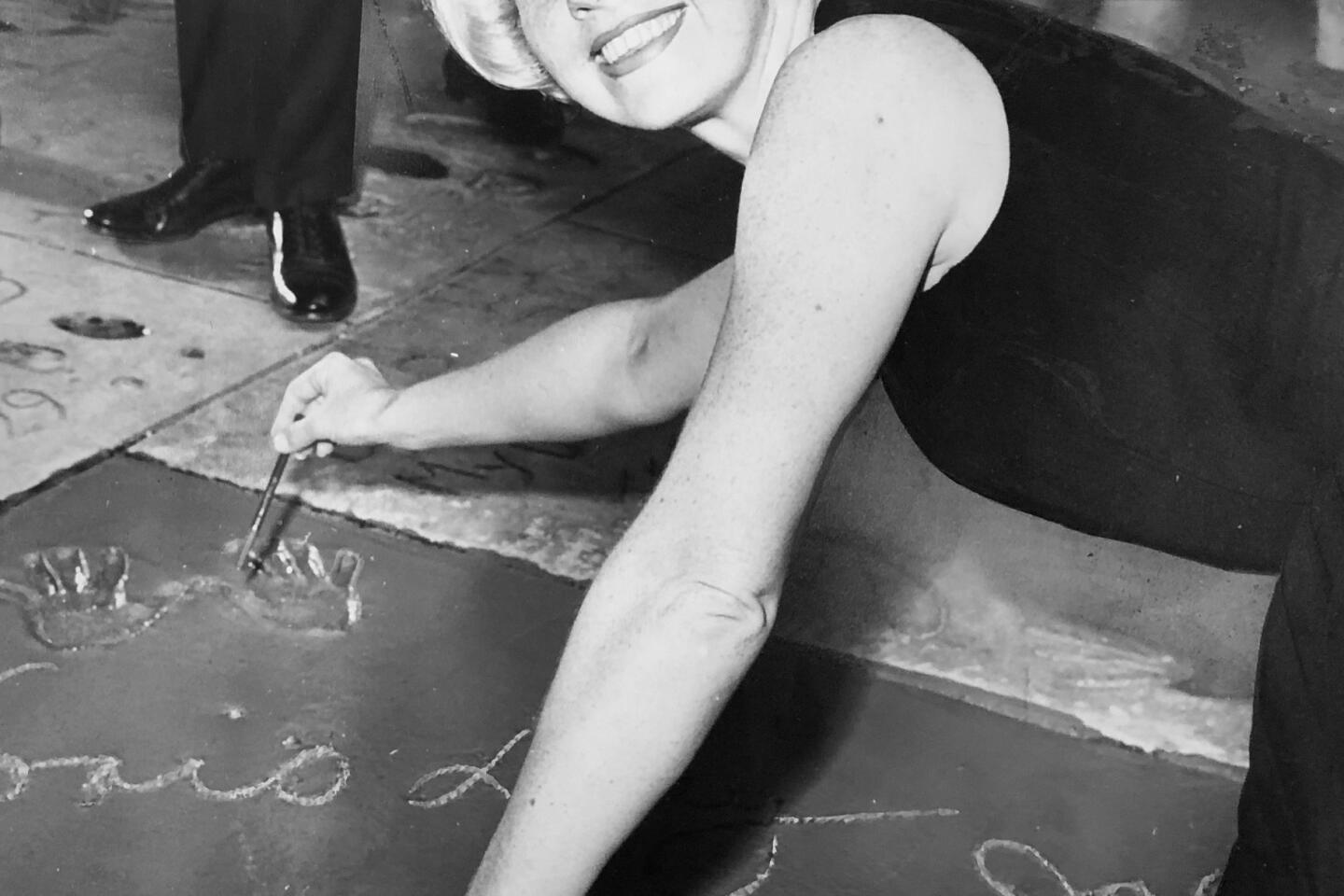

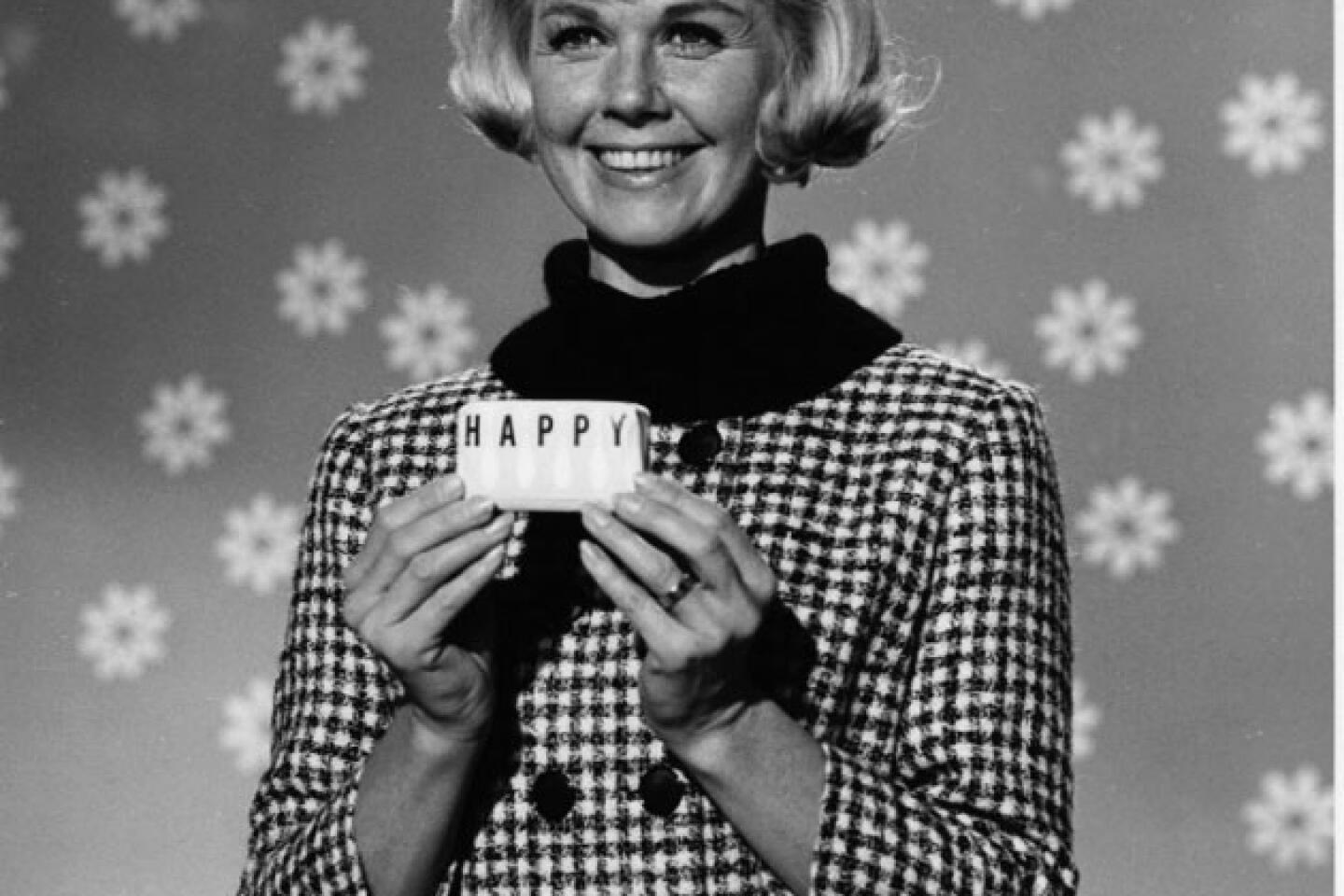

Doris Day arrived in Hollywood in the late 1940s already a celebrity, a big-band singer on her way to becoming a movie star. She had early success in light musicals, but as they fell out of fashion she modernized herself in a way that probably confused mid-20th century America: With a bubbly screen presence and a blinding smile, Day was the rare movie heroine who held a great job while having the requisite romance.

Women wanted to be her and men wanted to marry someone like her. The equation proved to be box office gold.

Day died of pneumonia Monday at her Carmel Valley, Calif., home. She was 97.

She had been “in excellent physical health for her age” until recently, the Doris Day Animal Foundation said in an emailed statement.

In the early 1970s, Day walked away from Hollywood, spending most of the ensuing decades in her beloved Carmel, where she was an outspoken animal rights activist.

Doris Day dies: Reactions as Hollywood icon remembered as ‘glorious and inimitable’ »

On screen, she effectively traded barbs with leading men and marched into the workplace in such lighthearted movies as “Pillow Talk” (1959) and “Lover Come Back” (1961), two of the three films she made with Rock Hudson. She received her only Academy Award nomination for “Pillow Talk.”

“Her persona hit a cultural mother lode, tapping into what the average postwar woman was about,” Drew Casper, a USC film professor, told The Times. She “was way ahead of her time, a feminist before there was feminism.”

From 1948 to 1968, Day appeared in 39 films, most often as the wholesome girl next door. At age 46, she made her last film, “With Six You Get Eggroll.”

Day’s body of work shows “how much of an icon she was, how much she became in her own way the female equivalent of John Wayne or Clint Eastwood,” Times film critic Kenneth Turan once wrote.

She was such a natural that when director Michael Curtiz caught her taking acting lessons while making her first movie, “Romance on the High Seas” (1948), he told her to stop, she recounted in “Doris Day: Her Own Story,” her 1976 as-told-to autobiography by A.E. Hotchner.

Day “was an Actors Studio all by herself,” Hudson said in her autobiography. “Her sense of timing, her instincts — I just kept my eyes open and copied her.”

She was at her best in films that allowed her sultry voice and “wonderful way with a song” to carry some of the dramatic weight, Turan wrote, including “Calamity Jane” (1953) and “Young Man With a Horn” (1950), in which she played a band singer opposite Kirk Douglas’ trumpet player.

Doris Day: A guileless natural on screen and record, and a mystery even to her devotees »

Day also became one of the most popular singers of her generation. Next to Frank Sinatra, Day was “the best in the business on selling a lyric,” band leader Les Brown said in her autobiography.

Her rendition of “Sentimental Journey,” recorded with Brown and his Band of Renown in 1945, brought her a flood of letters from servicemen at the end of World War II. More than 50 years later, her version of the song made it into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Songs she sang were nominated for Academy Awards half a dozen times. Two won: “Secret Love” from “Calamity Jane,” a musical that was her favorite film; and “Que Será, Será (Whatever Will Be, Will Be)” from “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 movie that cast her against type as a neurotic American mother abroad. “Que Será, Será” was also inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, in 2012.

The “Secret Love” album sold well and made producers realize the potential for cross-promotion between movies and music, said Casper, who has screened Day’s movies in his USC classes because her talent and message “signified the very best of postwar culture.”

Yet her insistence on making mostly sunny, upbeat films earned the rancor of some feminists in the 1960s, who thought Day’s roles glorified an ideal woman who never really existed.

In a 1976 essay in Ms. magazine, film critic Molly Haskell presented an early revisionist’s view of Day’s career. She argued that Day was a proto-feminist who challenged “in her working-woman roles, the limited destiny of women to marry, live happily ever after and never be heard from again.”

In romantic comedies, her characters often had a career; she played an interior decorator in “Pillow Talk” and an advertising executive in “Lover Come Back.” Yet there was no arguing that the luminous blond entertainer — eternally perky and often dressed to the nines — set men aquiver.

“She conveyed a unique blend of innocent sexiness … that was not so much the woman next door as the woman you wished lived next door,” Times critic Charles Champlin wrote in 1988.

Doris Day’s screen-style legacy for working women was all about what to wear — not bare »

Novelist John Updike disclosed his deep-rooted crush on Day in a 1976 New Yorker essay: “Singing or acting, she manages to produce, in her face or in her voice, an ‘effect,’ a skip or tremor, a feathery edge that touches us.”

Movie exhibitors placed Day in their annual poll of top box-office stars 10 times during the 1950s and ’60s. Four times she held the top spot.

Her costars included leading men of her era — Sinatra in “Young at Heart” (1954), Clark Gable in “Teacher’s Pet” (1958) and Jimmy Stewart in “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” a thriller considered one of her finer films.

Of the hundreds of songs Day recorded, the lilting ballad “Que Será, Será” became her trademark. Day initially dismissed it as a nursery rhyme but adopted its refrain — “whatever will be, will be” — as her philosophy for dealing with a turbulent personal life at odds with her clean-cut screen presence.

“I’ve had a perfectly rotten life,” she told Hotchner.

Married four times, Day was beaten by her first husband, trombonist Al Jorden, while she was pregnant . She was divorced by 21; he later died by suicide. Her second husband, saxophonist George Weidler, abandoned her within months and said he did not want to be known as Mr. Doris Day.

When husband No. 3, Marty Melcher, the manager and architect of her career, died in 1968 after 17 years of marriage, she learned that he “had secretly contrived” to wipe out her fortune, Day told The Times in 1976.

He had lost $20 million of her earnings, possibly through bad investments, and left her $500,000 in debt. He also committed her to star in a television series without telling her.

“Just about the best thing Marty did for my mother was to die when he did,” her son, Terry Melcher, said in her autobiography.

She sued Melcher’s business partner, lawyer Jerome Rosenthal, for fraud and malpractice and was awarded almost $23 million in 1974. She settled for $6 million rather than drag out the case on appeal.

Although she had sworn off marriage, Day married Barry Comden, a restaurant manager, in 1976. When they divorced in 1981, he claimed she preferred the company of dogs.

Despite hating the idea of doing TV, in 1968 Day was on the set at CBS for “The Doris Day Show” within six weeks of Melcher’s death, determined to earn back her fortune and enough money to sue Rosenthal.

After five years, Day refused to renew the sitcom. In 1981, she moved to Carmel, the Monterey Bay community she fell for while making the 1956 film “Julie,” and devoted much of her life to animal welfare.

Doris Day’s hotel in Carmel is one of the pet-friendliest around »

In 1971, she had helped found Actors and Others for Animals, which rescues stray and mistreated animals. She also pushed for animal rights through the Doris Day Animal Foundation and the Washington-based Doris Day Animal League.

She released “My Heart” in 2011, an album of old recordings that was her first in 17 years, with proceeds earmarked for her foundation. With her son, she also was part-owner of the Cypress Inn, a Carmel hotel that welcomes pets.

In 1985, the Christian Broadcasting Network approached Day about hosting a talk show called “Doris Day’s Best Friends” that would feature celebrity guests and animals. It aired for two years.

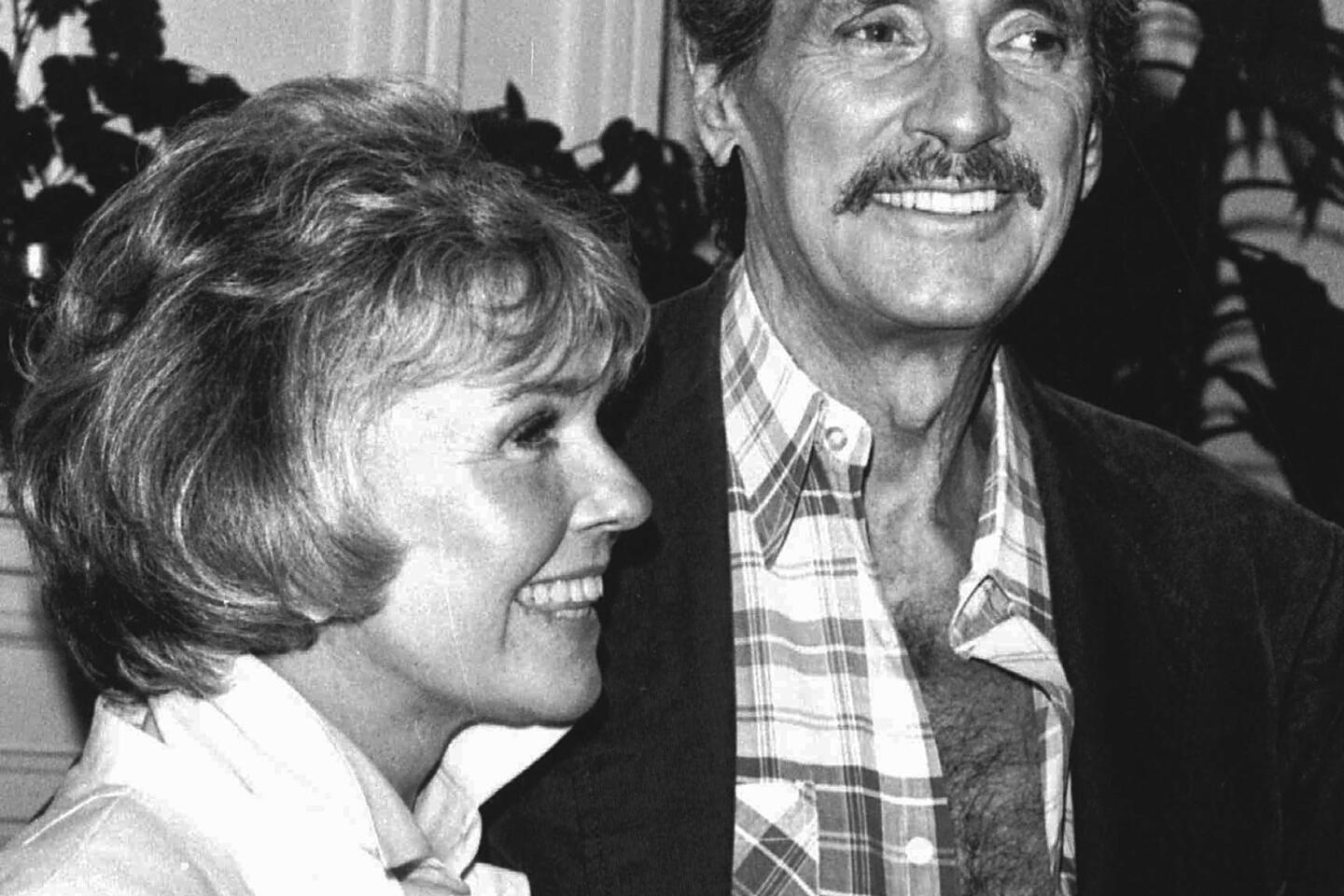

Hudson was a natural first guest, Day later said, because he loved dogs as much as she did. Yet when he came to Carmel in mid-July for filming and a news conference, Day and the press corps were shocked by his gaunt appearance.

Sick with AIDS, Hudson had yet to reveal his condition to Day or the public, but reporters immediately realized he was gravely ill. He would later reluctantly admit that he had AIDS, becoming one of the first major celebrities to acknowledge having the disease.

Doris Day helped introduce America to AIDS with empathy and love for Rock Hudson »

Despite needing rest, Hudson insisted on taping the show, which aired days after he died in October 1985. Day, her voice choked with emotion, taped an introduction that recalled how Hudson always told her, “The best time I’ve ever had was making comedies with you.” She said she felt the same way.

In a rare Hollywood appearance, Day reluctantly returned in 1989 to accept the Golden Globes’ Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievement.

When she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in 2004, she said fear of flying kept her from the White House festivities. Although she said she was “thrilled” to receive a lifetime achievement award from the Los Angeles Film Critics in 2012, Day once again stayed away.

Doris Kappelhoff was born in Cincinnati and named for her mother’s favorite silent-screen star, Doris Kenyon. Day was known to prevaricate about her age, but Ohio birth records confirm that she was born April 3, 1922.

Her father was a music teacher who left his wife for the mother of Doris’ best friend when Day was 11. Her mother moved Day and her older brother to suburban Evanston, Ohio, and worked in a bakery.

At 12, Day and a partner won a $500 dance contest. But on the eve of moving to California in 1937, Day badly injured her leg when a train struck the car she was in.

Her dancing career was over. But when she sang along with radio tunes during her lengthy hospital stay, her mother realized Day had a remarkable voice and arranged for singing lessons.

Soon Day — who couldn’t read music — had an unpaid weekly singing gig on a local radio show. When Barney Rapp, a popular Cincinnati band leader, heard her rendition of “Day After Day,” he hired the teenager to perform at his nightclub.

“Kappelhoff” was too unwieldy a surname, Rapp told her. He suggested “Day” for the song that she was making her own. Soon she was touring with big bands led by Bob Crosby, Fred Waring and Brown.

For a decade, starting in 1948, Day had 30 top-20 singles, including “Love Somebody” and “A Guy Is a Guy,” which both claimed the No. 1 spot. She recorded almost 30 albums.

I honestly believed every word of what I sang or spoke, and people respond to that.

— Doris Day

One of the last of the studio-contract stars, Day began making the big-band musicals that Warner Bros. churned out.

Never comfortable performing live, she took to recording and acting for the camera “like a duck to water,” she once recalled.

In 1951’s “Storm Warning,” Day appeared with Ronald Reagan. Day dated the future president and said he was the only man she knew who loved to dance.

At 28, she bought her first house, in Toluca Lake, and for the first time lived full time with her son from her first marriage; he was 8. Even after her son was an adult producing hit records for the Byrds, the Beach Boys and the Mamas and the Papas, Day expressed guilt over allowing her mother to raise him while she built her career.

At Burbank City Hall on her 29th birthday in 1951, she married Melcher, who was her agent. At first, her son adored Melcher, who adopted Terry but treated him harshly as he grew up. After Day saw Marty Melcher hit her son in the 1960s, the marriage was never the same. By the time Melcher died, their relationship was platonic.

Her son stepped in to help manage his mother’s career and other projects. He died of cancer at 62 in 2004.

When asked why she thought audiences had embraced her, Day once recalled, “I honestly believed every word of what I sang or spoke, and people respond to that.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.