Doris Day: A guileless natural on screen and record, and a mystery even to her devotees

In the 1960 family comedy, “Please Don’t Eat the Daisies,” Doris Day plays a housewife married to a drama critic. As she tries to dress up for a Broadway opening, domestic chaos explodes: The kids are running amok, the dog is barking and time is running out. The scene is a tour de force of comedic high jinks, and she breezes through it with the utmost ease. Years later, film critic Rex Reed recalled that performance to her in awe. She couldn’t even remember having done it.

Whether acting or singing, Day, who died on May 13 at the age of 97, was effortless, natural, believable and heart-tugging.

In 1944, she was every soldier’s sunny, sexy blond girlfriend, beckoning them home safely with “Sentimental Journey,” a colossal hit of the war years. A dozen years and a string of hit movie musicals later, Day recorded her defining song, “Whatever Will Be, Will Be” (Que Sera, Sera),” a child’s lullaby that served as a postwar panacea. For four years in the 1960s she was named the No. 1 box-office star in America.

Day turned both dialogue and songs into intimate conversation. When the music played, she sang to you as though from across a pillow, with perfect conversational phrasing and a gentle, husky, slightly breathy tone that caressed the ear like the lick of a cat’s tongue. According to Sue Raney, the veteran pop-jazz singer who saluted Day on her 2006 album “Heart’s Desire: A Tribute to Doris Day,” “Even when she was singing a sad song, she had a smile in her voice.”

Yet there was also a tinge of mystery in Day to ignite the imagination.

In interviews, she skillfully gave the illusion of candor, delivering platitudes with the utmost sincerity while revealing almost nothing. Cabaret singer Mary Cleere Haran was Day’s off-camera interviewer in a 1991 documentary, “Doris Day: A Sentimental Journey.” Haran tried gently to lead the star into deeper memories of her childhood and her marriages. The pain of it proved too much for Day, who burst into tears.

Therein lies the wistfulness of Day’s singing. You can feel it on “Day by Night,” her 1958 ballad album with a melancholy nighttime theme; and on “Duet” (1961), on which Day is joined by the jazz trio of André Previn. Both albums appear in a massive, four-volume release of the recordings that followed her early years as vocalist with Les Brown and His Band of Renown. The sets hold a dismaying amount of dreck, yet Day applied the same conviction and believability to everything from the cheesiest polkas to Harold Arlen.

Did she know the difference?

“Nah!” Previn told me in 2012. “But she was a very good singer.”

Day recorded commercially from 1940 to 1967, and in those years her intimate storytelling gifts grew to rival those of Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Peggy Lee.

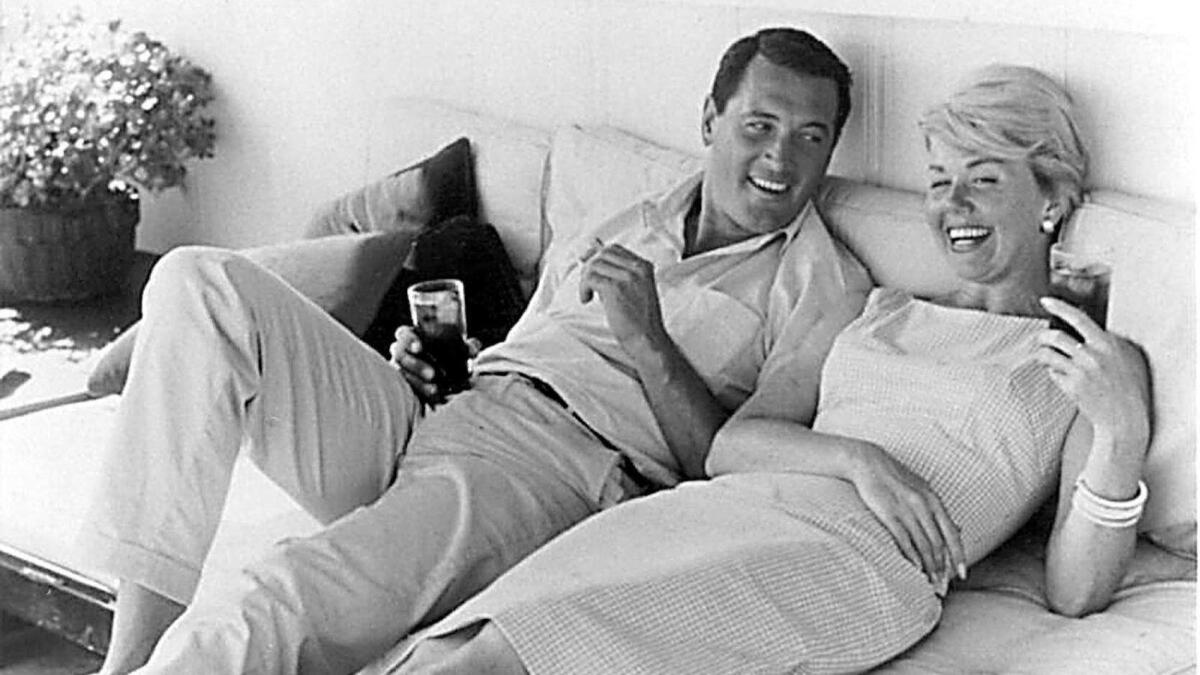

Among her films, there is no cinematic milestone, nothing studied and analyzed for its greatness. A few came close, and Day met the challenge. In “Love Me or Leave Me” (1955), she convincingly brought out the toughness and heartbreak of Ruth Etting, the 1920s gangster-moll torch singer. In 1956’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” Day is a retired singing star and mother who becomes embroiled in a political assassination scheme in Morocco. So impressed was Alfred Hitchcock by her instincts that he barely directed her. But her defining film remains 1959’s “Pillow Talk,” with Rock Hudson, which sealed her fate as a coy but sophisticated temptress whose virtue could be unlocked only through proper channels.

Her on-screen persona wasn’t complete fiction. Previn, the renowned composer, maestro and pianist, rolled his eyes at the memory of “Duet.”

“She was so determined to be Miss America,” he told me. “I was at her house trying to pick tunes, and at one point she said, ‘Listen, it’s 5 o’clock; would you like a drink?’ Yeah, I would. She ran over to the corner, where she had a big soda fountain, and she said, ‘Chocolate or vanilla?’ ”

Day fans rue the two great lost opportunities of her film career. She was asked to star in “South Pacific,” but her husband and manager, Martin Melcher, set her price too high, and Day, who was afraid of flying, wouldn’t board a plane to Hawaii for shooting. Later, she turned down the role of the middle-aged sexpot Mrs. Robinson in “The Graduate,” because it entailed nudity.

In 1968, Melcher died, and Day found herself a Hollywood cliché: the female star who had turned a blind eye while her floundering manager-husband blew her fortune. “The Doris Day Show,” which ran on CBS for five seasons, enabled her to pay off their debts. Despite one more marriage, Day, from then on, found comfort in her dogs and founded the Doris Day Pet Foundation for animal welfare.

A few years later, she revealed more of herself in a memoir, “Doris Day: Her Own Story,” coauthored by A.E. Hotchner. Afterward, Day seemed uneasy at having exposed so much and ill at ease on the publicity trail; she was snarky to Barbara Walters for pressing her on some of the seamier details in the book.

On some level, Day knew that what becomes a legend most is elusiveness. She emerged from retirement in 1985 for the one-season run of “Doris Day’s Best Friends,” a low-budget cable series on the Christian Broadcast Network; the guests were a bevy of animals and her celebrity friends, notably a dying Rock Hudson. From then on, Day teased fans with half-promises of a comeback. In 1989, she appeared at the Golden Globes to accept the Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievement. Day, a vision in white, confided to the masses: “I’ve been away much too long…. It’s been a wonderful life, and I’m not finished yet. I think the best is yet to come, I really do, and I want to do some more.” She didn’t.

Many wonder why she never received a lifetime achievement Oscar or a Kennedy Center Honor. Day refused to travel; beyond that, she didn’t seem to care. In recent years, she tantalized the crowd of die-hard fans who flew in from all over the world to sing happy birthday to her beneath the balcony of her Carmel home. Would she appear or wouldn’t she? Sometimes she did, waving down at them, apparently happy and well.

In 2012, Sue Raney attended a 90th birthday party held for Day in Carmel, Calif.

“Nobody knew if she was gonna come. When she walked in, everybody was in tears at the joy of seeing her.”

On Raney’s wall in Sherman Oaks hangs a letter Day sent in response to the CD. Written in Day’s familiar curly penmanship, it captures the breathless sincerity that buoys almost all the work she left behind.

“Dear dear Sue... I’m also sorry that you paid tribute to me when I should pay tribute to you. Your CD is so exquisite, and I’m playing it just about every day. All I can say is, God did a little dance around you. Stay well and sing! Love, Doris.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.