In California’s backcountry, seeking movie backdrops

Every year, thousands of film fans become location scouts of sorts as they search for scenes shot in the Alabama Hills, a badlands that has appeared in more than 700 movie and TV productions.

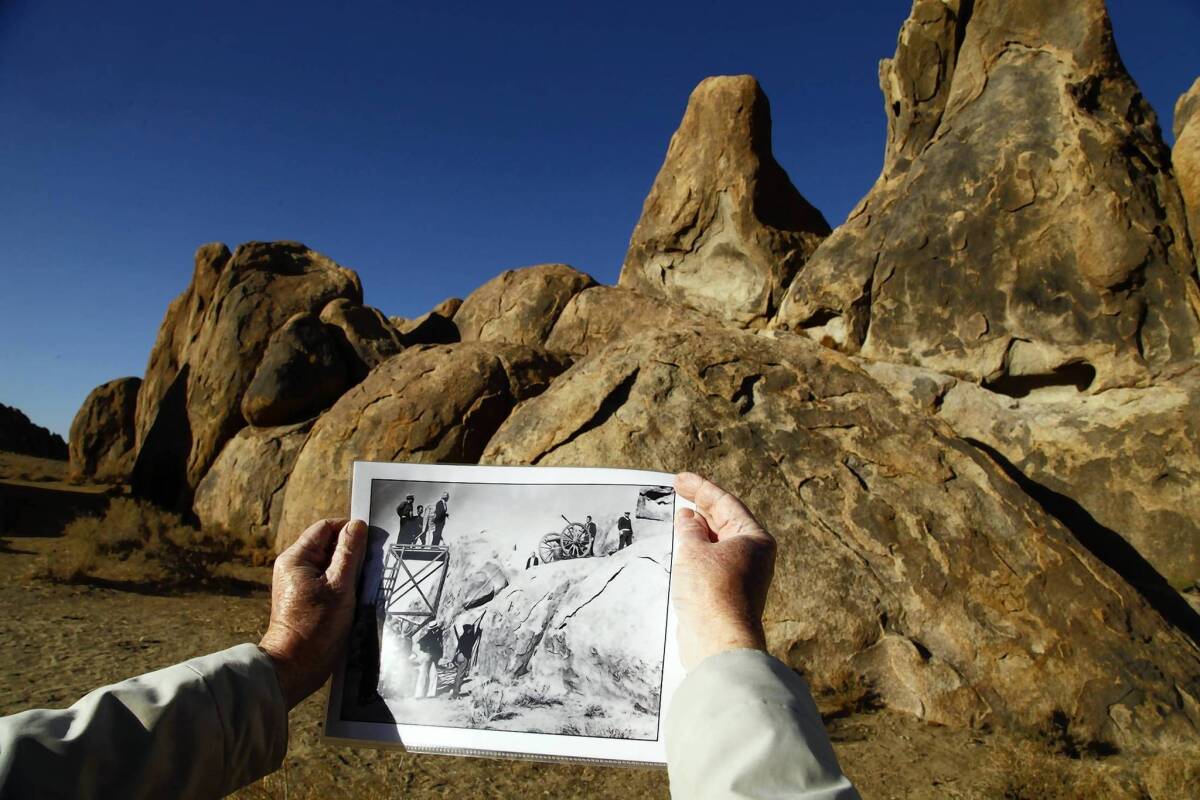

As howling winds tore through the eastern Sierra, Dan Gillespie and his wife Carol trudged along a narrow gravel path, their eyes alternating between photos they carried and the contours of a cove guarded by granite walls.

At one point, Carol held up a photograph of a campfire scene in "Django Unchained," which is set in the South just before the Civil War. She moved the photo to the left, then to the right. She squinted, then broke into a smile.

Pointing to a nearby rock, she said that actor Jamie Foxx "stood right there."

The Gillespies and three other people on this outing were location scouts of sorts — and they had just found their prize.

Like thousands of other film buffs and historians who flock here every year, they found the location of a movie scene shot in the Alabama Hills, a high-desert badlands of gullies, canyons and outcroppings at the foot of Mt. Whitney that has appeared in more than 700 movie and television productions.

At times the search on this early spring day resembled a Hollywood producer's idea of a spoof. Icy gusts stirred up sandstorms and blew fistfuls of photographs out of benumbed fingers. Heaps of boulders appeared one way in the long shadows cast by the morning sun, and a different way altogether at noon.

"We're doing the Lone Pine shuffle — looking down at a photograph, then looking up at the landscape, then looking down on the picture again without tripping," said Kent Sperring, visiting from Duluth, Ga. "We've all taken a tumble or two during these investigations."

The searchers were engaging in an activity started in the 1980s by film buff Dave Holland, whose efforts to find the exact spots of movie scenes helped popularize the Lone Pine Film Festival.

Locals talk about how Holland, who died in 2005, used promotional photos to determine that a tall, cucumber-shaped rock was a backdrop in scenes of Gene Autry and his sidekick Smiley Burnette sitting on their horses in "Boots and Saddles," Tim Holt escaping a posse in "Guns of Hate" and an Indian chase in "How the West Was Won" — films released in 1937, 1948 and 1962, respectively.

Today, location explorers use photos obtained at film conventions, specialty shops, film festivals and from the Lone Pine Film History Museum, which also offers tours — and GPS coordinates — of dozens of locations used in old westerns and "Star Trek," "Iron Man" and "Transformers."

Hard-core trekkers rely on "grabs," movie frames selected at random and printed off DVDs. Close-up shots are particularly challenging because they offer few clues beyond cracks and depressions on granite surfaces.

"It's a rather formidable game," said a smiling Dan Gillespie, a nuclear physicist who lives with his wife in Castaic. "Sometimes, having a photographic image snap into place with the surrounding terrain is a matter of walking 10 feet in a certain direction."

For inspiration, film buffs look to the 6-year-old film history museum, which houses a trove of vintage photographs and movie posters, props, costumes and vehicles used in productions that were part of the excitement of everyday life for much of the 20th century.

The ghosts of all those actors are still out there reenacting their best days."— Chris Langley

"Our biggest exhibit is the surrounding terrain — and we'd like to keep it just the way it is," said museum Executive Director Chris Langley. "The ghosts of all those actors are still out there reenacting their best days."

The Alabama Hills and movies found each other in 1920 with the silent western "The Roundup," starring Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle.

Today, a box canyon where outlaws ambushed and killed all but one Texas lawman — who, with his Indian companion Tonto, went on to fight injustice in the American Old West — is known locally as "Lone Ranger Canyon."

The hill country in Northern India where three British soldiers and a water boy fought against seemingly insurmountable odds is marked by a plaque: "Gunga Din filmed here." A mining camp left over from the 1948 western "Yellow Sky" has become a permanent part of the terrain.

The landscape also is loaded with movie blank shell casings.

"I love that sound," Sperring said as a metal detector he carried sounded an alarm over a patch of sand where a running gun battle had been staged 78 years earlier for the first Hopalong Cassidy movie.

Sperring picked up a badly eroded movie blank shell that had never been fired. "Prove to me that Hoppy didn't drop this right here in 1935," he said with a laugh.

Longtime Lone Pine resident Kerry Powell recalls the early days of moviemaking in the Alabama Hills as she stands in the Beverly and Jim Rogers Lone Pine Film History Museum, which she helped establish. More photos

Kerry Powell was a girl in 1938 when a Hollywood studio rolled into town to shoot "Gunga Din."

"It was so exciting when my father took us out to see the elephants lumbering around the rocks and sage that substituted for India," Powell recalled in a room of her home here festooned with film posters and autographed photos of movie stars including Roy Rogers, Kirk Douglas, Ann Baxter and Virginia Mayo.

During the filming of "The Gunfighter" in 1949, Powell was working in the laundry room of her in-laws' Lone Pine motel when, she recalled, "I heard that voice and froze in my tracks. I turned around and there he was, Gregory Peck. He wanted to know if we had some extra towels."

Moviemaking and scene hunting — along with hiking, photography and rock climbing — have become so popular in this area that locals have drafted a plan to transform 18,000 acres now managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management into a national scenic area. The designation would strengthen protections against subdivisions, mining operations and wind and solar energy farms and guarantee permanent public access.

More important in this eastern Sierra community of 2,200 people, the designation would solidify the region's role in film and television productions, shoring up the local economy. Movie, TV and commercial productions generated an estimated $10 million in fees, sales and taxes in Inyo County last year.

Map of movie locations in and around the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) said she will consider legislation to grant National Scenic Area status if it has local support. Federal land-use designations are controversial in Inyo County, however. Just 2% of the 10,000-square-mile region is privately owned, and 65% of the publicly owned land is already designated as wilderness. Some local officials prefer to see public lands remain available for industrial uses including mining and renewable energy.

As the five scene hunters continued their search, gale-force winds kicked up dust and sent them scurrying for cover. They were looking for locations from "The Oregon Trail," a 1936 western shot here because it looked like the frontier country of hazards, heroes and scoundrels where the action takes place.

Today, that movie is known as "John Wayne's lost film" because it mysteriously disappeared after its release. All that remains are promotional stills and a few minutes of footage.

The searchers were looking for the backdrop of a scene with Wayne standing righteous atop a boulder, a coiled rope in one hand and a six-shooter in the other.

But the brutal weather forced the searchers to surrender.

As they prepared to head home, Sperring scanned the ridgelines and said, "The rocks don't change. We'll get it next time."

Contact the reporter | Contact the photographer

Follow Louis Sahagun on Twitter

More great reads:

Local man eats at 6,297 Chinese restaurants

14-year-old 'Albanian Bear' always up for a fight

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.