It was late on a chilly night when I descended a winding mountain road to Shelter Cove, one of the few California coastal communities I’d never visited.

I checked into the Inn of the Lost Coast, dropped my bags on the floor of my room and opened the back door to see how close I was to the water.

The essence of the sea drifted up from the base of a cliff and I took in deep drafts of salt air. I kept the door open so I could hear the tide lapping against the rocks, a concert as old as time, and descended into a sleep as deep as the sea.

Catch up on Steve Lopez’ road trip and photographer Allen Schaben’s images of California’s 1100 miles of coast »

There is no stage like the one where land meets surf, no drama more mesmerizing.

Photographer Allen Schaben and I traveled 1,100 miles in five weeks, starting at the Oregon border.

As I said a few weeks ago, my crush on the coast began half a century ago with summer vacations in Santa Cruz, and it grew deeper on this trip.

So, too, did my determination to keep an eye on the public officials whose job is to uphold the protections laid down by the Coastal Act, which turned 40 this year.

The anniversary wasn’t the only thing that begged review of a powerful agency with a sacred duty. The clumsy firing of Executive Director Charles Lester in February, by the politically appointed commissioners, was a debacle that demoralized the agency’s paid staff and enraged hundreds of people up and down the coast.

Many of them believed this particular set of commissioners, led by Gov. Jerry Brown’s four appointees, was dangerously cozy with developers and their hired guns, and was trying to exert more control over the agency and support construction even when their own staff experts determined that doing so would violate the Coastal Act.

Commissioners carp and crab about such criticism. But commissioners’ own shabby behavior — not all of them, but several of them — exposed a sloppy culture of ethical lapses and broken rules.

Thanks to scrutiny by outraged agency watchers and the L.A. Times, investigations are underway and legislative reforms in play.

The fragile, awe-inspiring shoreline and the public deserve better, and you’re reminded of that along every mile of the coast. Ordinary people fought in the late ’60s and early ’70s for conservation of fisheries and estuaries, and for enhanced public access, and the achievements over four decades have been extraordinary.

The agency’s delicate duty is to balance private property rights against public interest, and the entrenched bureaucracy — challenged by chronic understaffing — has frustrated many.

Yet, because wise commissioners have managed over the years to push back against nuclear power plants and sprawling developments, Californians can visit rocky shores, pristine beaches and ocean-view bluffs where marine animals, birds and plant life flourish.

More battles remain.

As Coastal Act author Peter Douglas famously said: “The coast is never saved; it’s always being saved.”

In Half Moon Bay, I visited a beach that was a popular destination for decades, until a billionaire blocked access.

Farther south, a sand-mining operation is causing an astonishing level of beach erosion.

I toured a dune near Monterey, where a long-frustrated developer vows to begin construction of a 368-unit hotel and residential project this fall, despite fears of harm to nesting birds protected by the Endangered Species Act.

At Hollister Ranch, wealthy landowners including singer Jackson Brown enjoy a slice of California much like what the first Spanish explorers encountered, while security guards keep average Californians from the ranch’s wet sand — which is public land.

Miles south, at Huntington Beach, a proposed desalination plant seems to be more of a money-making scheme than a well-conceived response to drought.

The Newport Banning Ranch proposal — by oil companies and their real estate partner — would turn the largest undeveloped, privately owned land on the Southern California coast into a massive residential, hotel and commercial enterprise despite claims of damage to environmentally sensitive habitat.

1/121

A woman takes a break from riding her horse on Imperial Beach, one of only a few places along the coast where horses are allowed.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 2/121

Palm fronds reveal a surfer, a couple and children taking in sunset at Windansea Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 3/121

The tide splashes up on the beach at sunset on a warm summer evening at Windansea Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 4/121

Backdropped by San Diego’s skyline, former Sen. James Mills, 89, stands at his Coronado apartment with the bike he rode from Sacramento to San Diego in 1972 to promote Proposition 20, which created the Coastal Commission and led to the Coastal Act.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 5/121

Children camping at Campland on the Bay paddle around on body boards in the warm waters of San Diego’s Mission Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 6/121

A view from the Torrey Pines Gliderport cliffs, overlooking Black’s Beach and Torrey Pines State Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 7/121

A California sea lions basks in the evening sunlight while resting on a rock in the La Jolla Marine Reserve, one of 11 California marine protected areas (MPAs).

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 8/121

A bod surfer is upended amid the crashing shorebreak at Windansea Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 9/121

A surfer heads in by a fire pit, hammock and palapa at dusk at San Onofre State Beach in San Clemente.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 10/121

Mila Renieri and Diego Merli of Milan, Italy, play on a homemade teeter-totter at San Onofre State Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 11/121

A “no beach access” sign is posted at Dan Blocker Beach scenic viewpoint. The beach is one of several in Malibu that don’t allow public access.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 12/121

RV campers have an ocean view, just across from Pacific Coast Highway at the Malibu Beach RV Park in Malibu.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 13/121

A kayaker checks out the clear waters of Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 14/121

A snorkeler swims around a reef/ rock formation at Crescent Bay, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 15/121

A snorkeler looks for fish at Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 16/121

Garibaldi, the California state fish, swim and feed on rocks at Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 17/121

Small fish swim at the reef at Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 18/121

A surfer rides a wave at sunset at “Old Man’s” surf break at San Onofre State Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 19/121

A bodyboarder rides a wave at Crescent Bay, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 20/121

Anders Hamborg rides a wave before his shift working as a Huntington Beach city lifeguard on a warm summer day in Huntington Beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

21/121

A view of the beach through a telescope at Pacific City, a new 31-acre mixed use development in Huntington Beach, also known as Surf City U.S.A.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 22/121

The site of the proposed Banning Ranch development now before the Calif. Coastal Commission.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 23/121

The tide rolls in at twilight at the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) nuclear power plant located on the border of San Diego County and San Clemente.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 24/121

A view of the AES Huntington Beach Generating Station, where an ocean water intake pipe is located that uses a technique of once-through cooling that is harmful to marine life scheduled to be phased out by 2020. The California Coastal Commission is holding a hearing on the proposed Poseidon Huntington beach Desalination project September 7/8. Poseidon would operate next to the AES power plant and use it’s ocean water intake pipe.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 25/121

A dolphin leaps out of the water with a view of south Laguna Beach in the background on Aug. 12, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 26/121

A pod of dolphins leaps out of the water with a view of south Laguna Beach in the background on Aug. 12, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 27/121

The Spirit of Dana Point, a traditionally built replica of a 1770s privateer schooner used during the American Revolution, takes a sunset cruise past The Headlands, center, and The Strand at Headlands development, left, in Dana Point. The Coastal Commission approved the 121-acre development known as The Strand at Headlands in 2004, but only after a decades-long fight between conservationists and the developer.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 28/121

The orange glow of the setting sun shines through palm trees on a warm summer evening in Heisler Park, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 29/121

Beach combers enjoy a warm summer evening exploring the ocean and coastline of Main Beach, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 30/121

Couples enjoy a sunset on a warm summer evening in Heisler Park, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 31/121

Beach combers are silhouetted by the sky’s glow while exploring the rocks at sunset on a warm summer evening in Heisler Park, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 32/121

Children run along the beach at twilight near the Crystal Cove Beach Cottages.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 33/121

The sun sets over the Crystal Cove Beach Cottages in Newport Beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

34/121

Kayakers take a scenic cruise in Monterey Bay on a summer day in Monterey. In the background, sand dunes line the coast where the proposed hotel and condominium Monterey Bay Shores development in Sand City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 35/121

Isabella, 9, and Holden, 7, roast marshmallows over a beach fire with their parents, Steve and Amy Knuff of Aliso Viejo at twilight at Crystal Cove Beach Cottages.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 36/121

Incoming tide rolls onto the beach at twilight at Crystal Cove Beach Cottages. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

37/121

A photographer captures the sunset over the ocean in Rancho Palos Verdes. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

38/121

The Point Vicente Lighthouse illuminates the landscape at twilight in Rancho Palos Verdes. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

39/121

A person climbs up the giant Point Mugu Sand Dune, across from Thornhill Broome Beach State Park in Ventura County.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 40/121

Taylor Geer and Marissa Acosta of Thousand Oaks relax on top of the giant Point Mugu Sand Dune, across from Thornhill Broome Beach State Park in Ventura County. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

41/121

Kids play on a stand-up-paddleboard at Leo Carrillo State Park in Malibu. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

42/121

Vivienne Lee, 7, of Thousand Oaks, jumps across rocks under the arches of a rock formation while watching the tide roll in at twilight at El Matador State Beach in Malibu. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

43/121

Keenan Yoo watches the waves crash at twilight at El Matador State Beach in Malibu. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

44/121

A tidal inlet reflects the surrounding landscape as a couple walk with their dog at twilight along Arroyo Burro Beach County Park in Santa Barbara. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

45/121

A Blue Heron flies over the Naples State Marine Conservation Area. Phil McKenna, president of the Gaviota Coast Conservancy, says the portion down-coast of Point Conception contains approximately 50% of its remaining rural coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 46/121

A man fishes in the ocean at sunset at Arroyo Burro Beach County Park in Santa Barbara.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 47/121

A deer takes a break from grazing to look out over the meadow in Cambria.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 48/121

A man walking his dog is viewed underneath a Cypress tree canopy over the beach boardwalk along Moonstone Beach in Cambria.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 49/121

A surfer rides a wave near a rock formation in Morro Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 50/121

The sun, filtered by forest fire ash and fog, goes down at the Morro Bay Marina, with a view of Morro Rock and sailboats.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 51/121

Surfers walk down the beach after surfing in front of Morro Rock.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 52/121

A windmill lines an undeveloped stretch of coast along Cayucos’ Estero Bay with Morro Rock visible in the background.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 53/121

A child bundled up in a thick wetsuit, cap and life jacket, skips to the water’s edge with an adult taking them body boarding in Morro Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 54/121

A child toting sand toys heads across the sand dunes at Morro Bay State Park in Morro Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 55/121

The tide fills in between jagged rock and cliff formations at Montaña de Oro State Beach in Los Osos.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 56/121

The tide fills in between jagged rock and cliff formations at Montaña de Oro State Beach in Los Osos.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 57/121

Elephant Seals battle one another on the beach rookery at Piedras Blancas State Marine Reserve, San Simeon.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 58/121

A scenic view of the setting sun shining through the fog along the Big Sur coastline. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

59/121

A scenic view of a waterfall spilling onto the beach at Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Big Sur coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 60/121

A scenic view of an iconic California coastline gem, the Bixby Bridge, Big Sur.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 61/121

Tourists sit together at a lookout point while exploring the Big Sur coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 62/121

A scenic view taken from Rocky Point, looking out over the Big Sur coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 63/121

Elephant Seals gather on the beach rookery at Piedras Blancas State Marine Reserve, San Simeon.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 64/121

Kayakers take a scenic cruise on Monterey Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 65/121

A scenic view of Garrapata State Park in Carmel-by-the-Sea.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 66/121

A view of Carmel Sunset Beach on a summer day.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 67/121

A child climbs a dune on the site of a proposed, nearly 400-unit hotel and condominium development in Sand City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 68/121

A Western snowy plover, a threatened species protected under the Endangered Species Act, stands amid critical habitat at the site of the proposed Monterey Bay Shores condo and hotel development in Sand City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 69/121

Amid fog, Mark Massara, a decades-long coastal steward, surfs in front of Shark Tooth Rock at Martins Beach, where an access gate remains locked despite a judge’s order to landowner Vinod Khosla to to open the private gate and allow public access to the beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 70/121

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez revisits Santa Cruz, where he surfed as a boy.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 71/121

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez surfs in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 72/121

The sun illuminates the incoming tide as a child plays in the water near Twin Lakes State Beach in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 73/121

A harbor seal lets out a yawn while relaxing on the rocks at Pigeon Point Light Station near Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 74/121

A sailor heads out to sea from Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 75/121

A mural on a beach cottage wall at Martins Beach, where an access gate remains locked despite a judge’s order to landowner Vinod Khosla to to open the private gate and allow public access to the beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

76/121

The sun sets as a crew team glides through the water near Lighthouse Point in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 77/121

A tourist takes in the coastline scenery at Pigeon Point Light Station near Santa Cruz. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

78/121

A view of the scenic Pigeon Point Light Station State Historic Park in Pescadero.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 79/121

Sailboats and stand-up-paddle boarders share the water off Lighthouse Point in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 80/121

Ash from a nearby forest fire creates a yellow-hued sky at sunset at Natural Bridges State Beach in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 81/121

A view of one of California’s most beloved coastal gems: the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco skyline from the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 82/121

An egret searches for breakfast on a foggy morning at Bolinas Lagoon Nature Preserve in Stinson Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 83/121

A family walks across the beach amid the fog at Dunes Beach in Half Moon Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 84/121

A man checking the surf is silhouetted by evening sunshine reflecting off the ocean amid fog at Dunes Beach in Half Moon Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 85/121

Harbor Seals relax in the mud at low tide on a foggy morning at Bolinas Lagoon Nature Preserve in Stinson Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 86/121

A crab crawls through the mud at low tide at Bolinas Lagoon Nature Preserve in Stinson Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 87/121

White pelicans and sea gulls perch on a sand bar in Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 88/121

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez, left, gets a kayak tour through the eel grass from Amy Trainer, right, deputy director California Coastal Protection Network.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 89/121

A coyote hunts for food along the shore in Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 90/121

Tom Baty, a local environmentalist, has a collection of Japanese glass fishing floats he found on the beach over the years. They are used to hold up fishing nets.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 91/121

Tom Baty has been involved in the fight to close the oyster farm on Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 92/121

A harbor seal checks out kayakers in Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 93/121

Steve Lopez, left, gets a kayak tour from Amy Trainer, in white kayak, Brett Miller and Cicely Muldoon.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 94/121

Remnants of oyster racks are part of a restoration project to remove 470 tons of marine debris and 5 miles of oyster racks in Drakes Estero

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 95/121

Amy Trainer, deputy director California Coastal Protection Network, kayaks past oyster racks in Drakes Estero.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 96/121

Amy Trainer, deputy director California Coastal Protection Network, kayaks past oyster racks in Drakes Estero.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 97/121

The tide pools at the scenic Shell Beach in Sea Ranch, Calif. Sea Ranch rallied a generation of coastal stewards demanding public access to the rugged and scenic beauty on the Sonoma County coast.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 98/121

A view of flowers overlooking the Pacific Ocean at Bodega Head, Bodega Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 99/121

A blue heron perches on a branch at The Hole in Bodega Head that was meant to hold a nuclear power plant. Photo taken at Bodega Head, Bodega Bay, Calif.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 100/121

A view of the rugged beauty of the Sonoma County coast.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 101/121

Couples take a scenic walk on the beach in Crescent City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 102/121

The rocky coastline of Shelter Cove.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 103/121

Fog partially obscures the high cliffs of the Lost Coast, where early conservation activists fought development in Shelter Cove.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 104/121

A woman watches the tide roll in on Black Sands Beach in Shelter Cove along the Lost Coast.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 105/121

A woman walks along Black Sands Beach in Shelter Cove.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 106/121

An evening view of the Mendocino County coastline in Northern California.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 107/121

A full moon rises at dusk over the protected Ma-le’l Dunes in Arcata, which contain eight distinct habitats.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 108/121

Sunset illuminates Battery Point Lighthouse and sea stacks in Crescent City on July 18, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

109/121

A surfer heads out at sunset to catch a wave near a sea stack in Crescent City on July 18, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

110/121

Flowers overlooking Enderts Beach near Crescent City on July 19, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

111/121

The Battery Point Lighthouse illuminates the night sky near sea stacks in Crescent City on July 18, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

112/121

A couple walks along the beach at Pelican Bay State Beach after crossing the California border from Oregon on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 113/121

Empty half-acre lots and paved roads are now part of the Lake Earl Wildlife Area on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 114/121

A blue heron lands on a tree branch amid the rich habitat of the south Lake Earl Wildlife Area, which was formerly private Bliss Ranch and is now public land near Crescent City on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 115/121

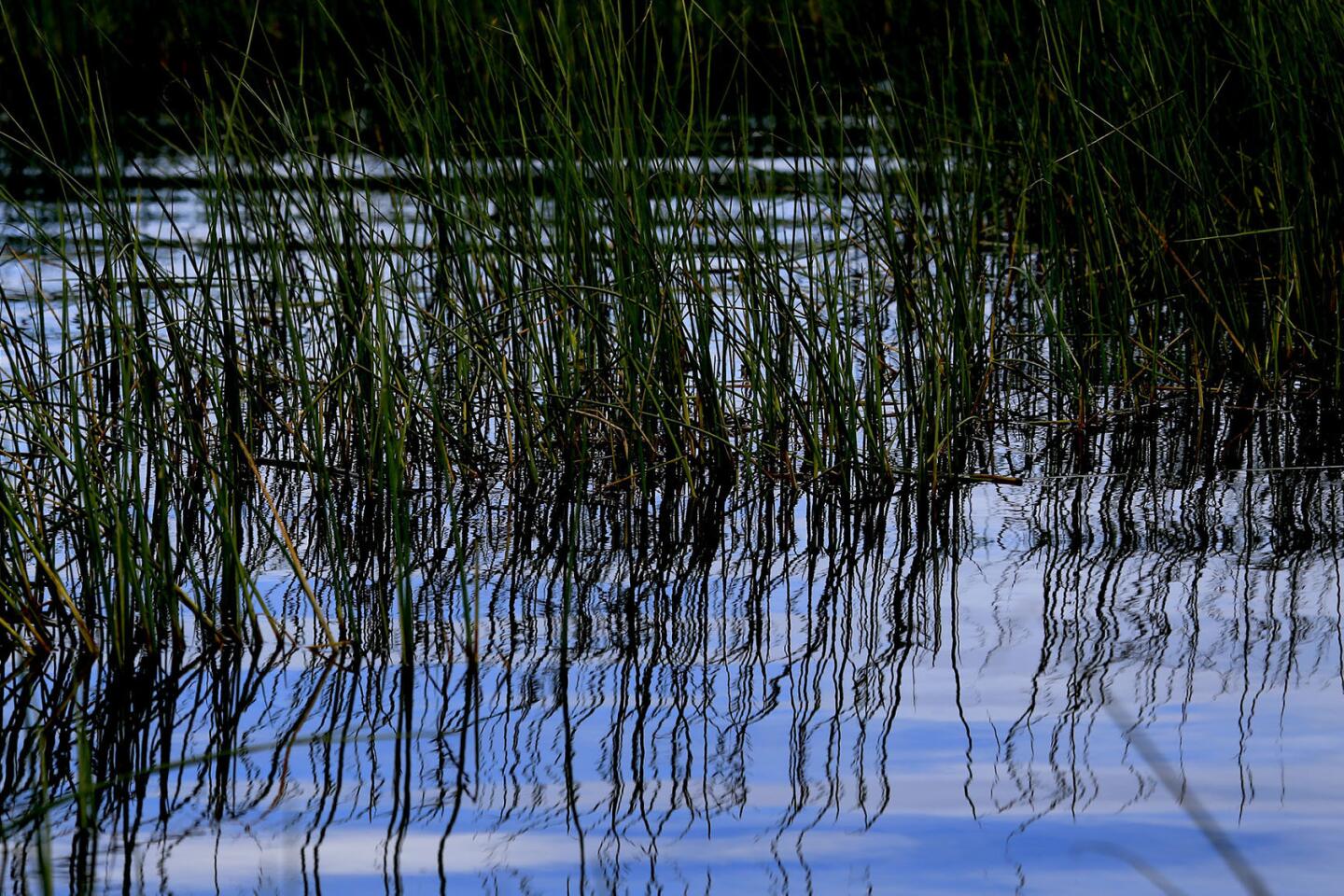

Water ripples among reeds in the near-empty half-acre lots and paved roads that are now part of the Lake Earl Wildlife Area.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 116/121

Sunset illuminates sea stacks and the coastline at False Klamath Cove in Redwood National Park near Crescent City on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 117/121

The sun sets behind trees at False Klamath Cove in Redwood National Park near Crescent City on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 118/121

A view of the Smith River National Recreation Area in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park on July 19, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

119/121

Times columnist Steve Lopez, right, kayaks with Grant Werschkull, left, co-executive director of the Smith River Alliance, on the Smith River National Recreation Area in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park on July 19, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

120/121

An elk grazes in the meadow at sunset in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park on July 19, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 121/121

Patterns formed by the wind and bird footprints in the sand at the Ma-le’l Dunes North, which contains eight different habitats, in Arcata on July 19, 2016. The dunes are highlighted as a victory for the coast after a years-long fight by conservationists to keep off-highway vehicles off the unique sand dunes.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) And in Malibu — and up and down the coast, for that matter — homeowners still find ways to keep the public off public beaches, a reminder that California’s leaders, including its coastal commissioners, have a responsibility to keep fighting for the Coastal Act’s requirement of enhanced access to low- and middle-income residents.

We all have to keep watching, not just occasionally, but always, and more closely than we have in the past.

News agencies that once regularly covered the Coastal Commission have been decimated by market forces. But the decline of accountability reporting makes it all the more important for journalists to prioritize what issues need covering.

California’s coast is of global interest — if you doubt that, listen to the cacophony of languages spoken at state beaches during the summer. Media worldwide have a stake in watching one of America’s most powerful resource protection agencies as it forges a new course.

In the coming months the Coastal Commission will hire a new executive director, choose a new chair and see the appointment of at least two new commissioners.

Where’s our state’s environmental hero in the midst of this historic change?

Beats me.

For months I’ve been trying to let readers know what Gov. Jerry Brown thinks of his state’s coast and the commission that’s supposed to guard it. His spokesman told me again last week that if he becomes available for an interview, they’ll let me know.

Brown’s non-voting but all-powerful Coastal Commission appointee, Janelle Beland, isn’t making herself available, either.

...Commissioners’ own shabby behavior... exposed a sloppy culture of ethical lapses and broken rules.

What we do know is that Brown proposed the lifting of Coastal Act review for low-income housing along the shore, and that Beland has challenged staff findings that environmentally sensitive habitat at Newport Banning Ranch would be harmed. She also pushed for parking fees along the Sonoma Coast to help bolster state parks revenues, despite claims that such fees will limit access for low-income families in areas where public transit is not an option.

What I take from all of this is that Brown is focused on his legacy tickets: the bullet train, Delta tunnels, climate change and budget pragmatism. If he gives a fig about the integrity of the Coastal Act he signed into law 40 years ago, it doesn’t show.

That’s all the more reason for the rest of us to be coastal stewards in the great California tradition begun by the likes of the late Bill Kortum, who warned that we must never back down or give up in the fight for preservation and access. It was an honor to meet in Bodega with Kortum’s wife, Lucy, and other pioneers who campaigned in 1972 for Proposition 20, which led four years later to the Coastal Act.

We’re blessed in this state. Our coast is a gift, and we share a duty to preserve and nurture it for our grandchildren, to teach them to do the same, and to foster appreciation as the Sea Odyssey program does in Santa Cruz, taking low-income inland students on marine-education excursions.

On the last leg of our trip, I stood at the Mexican border with Imperial Beach Mayor Serge Dedina, who said California’s beaches are our town centers, and what he sees on the faces of people from all walks of life is a sense of freedom and unbridled joy.

“I’m very proud of the fact that California embodies the idea that this is a public resource and every citizen has a right to access our magnificent and beautiful coast,” Dedina said. “It’s meant for all of us.”

My thanks to all the people we met between Oregon and Mexico, at Shelter Cove and the mouth of the Smith River, on the dunes of Humboldt Bay, the wild Gaviota coast and on Southern California’s urban beaches — surfers and sand lovers, botanists and biologists, activists and agitators.

Taking in the coast like this, from top to bottom, lifts the spirit and strengthens resolve. I know Allen Schaben feels the same, and if we can swing it, we’ll be back.

[email protected] | Follow on Twitter: @LATstevelopez

Weigh in at @JerryBrownGov #SaveYourCoast and (916) 445-2841 or email [email protected].

MORE FROM THE ROADTRIP

Why California’s northern coast doesn’t look like Atlantic City

California’s coast: How we come to care and why we sometimes go wrong

Our road tripping columnist confronts the dark side of oyster farming and the beauty of breaching whales