All week long, the ultimate destination was the Sonoma County coast.

That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy knocking around Tolowa Dunes, the Smith River and the Lost Coast last week.

Even though I’m a native Californian, I’d done very little exploring up there where the misty shore is rocky, elk run wild and giant redwoods creep down to the sea.

But I was eager to get to the place where the state’s coastal preservation movement took root four decades ago in a David-and-Goliath battle, and I knew I’d be meeting some of the visionaries to whom all Californians owe a debt of gratitude. Their story and the lessons learned are more important than ever, given project proposals big and small that could forever alter the California coast.

I knew I’d be meeting some of the visionaries to whom all Californians owe a debt of gratitude.

Let me set the scene first.

In the early 1960s, Pacific Gas & Electric Co. planned and began building a power plant at Bodega Head, one of the most jaw-dropping stretches of coast on the planet.

Meanwhile, developers were mapping plans for a monster residential project just north of Jenner at Sea Ranch, where sheep grazed between coastal bluffs and stunning pebble beaches.

Those projects had the support of local officials, who saw new streams of revenue.

But a small group of residents saw something else: the destruction of paradise.

They believed there would be irreparable harm to fisheries and the magnificent coastal habitat. In their minds, there’d be another crime, as well: the privatization of a public treasure.

The late Bill Kortum, a veterinarian from Petaluma, refused to let it happen.

When I got to Bodega Bay, I met with Kortum’s wife, Lucy, and his son, Sam, along with others who had lobbied, biked, hiked, knocked on doors and circulated petitions all those years ago to save the coast.

“He was out in the coastal areas and he’d be constantly driving the back roads,” said Sam, describing how his veterinarian father made house calls to the dairy farms and began recruiting his clients to the battle against unchecked development.

In 1968, Kortum and other rabble-rousers formed COAAST, Californians Organized to Acquire Access to State Tidelands.

The Kortum posse set up ironing boards outside grocery stores, spread out their materials and made their case.

“Bill would phone people, and when Bill phoned you, you go,” said Pete Leveque, a Santa Rosa Junior College marine biology teacher recruited to COAAST by Kortum.

Ernie Carpenter, a former Sonoma County supervisor, also answered the call.

“People would just coalesce into spontaneous ad hoc groups,” Carpenter said.

They backed a local measure to limit development, but it got drubbed. The coastal stewards kept at it, though.

As Kortum always told them, never back down or give up.

In Bodega, I met Carpenter and the others at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, which over the years provided the environmental science — along with other marine labs — that gave the muckrakers more clout.

Maggie Briare, a Kortum disciple, said limiting development wasn’t about “pulling up the ladder” after moving onto the heavenly coast. It was about making sure the very things that made the area so special were protected for everyone to enjoy.

Sam Kortum recalled the days when his weekends were never free. He was busy knocking on doors with his family, gathering support for conservation measures. All these years later, his mother was still not apologizing for that.

“It began with Bodega Head,” Lucy said of the site of the proposed power plant. But it was Sea Ranch “that really got Bill stirred up.”

The Kortum posse set up ironing boards outside grocery stores, spread out their materials and made their case.

1/121

A woman takes a break from riding her horse on Imperial Beach, one of only a few places along the coast where horses are allowed.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 2/121

Palm fronds reveal a surfer, a couple and children taking in sunset at Windansea Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 3/121

The tide splashes up on the beach at sunset on a warm summer evening at Windansea Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 4/121

Backdropped by San Diego’s skyline, former Sen. James Mills, 89, stands at his Coronado apartment with the bike he rode from Sacramento to San Diego in 1972 to promote Proposition 20, which created the Coastal Commission and led to the Coastal Act.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 5/121

Children camping at Campland on the Bay paddle around on body boards in the warm waters of San Diego’s Mission Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 6/121

A view from the Torrey Pines Gliderport cliffs, overlooking Black’s Beach and Torrey Pines State Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 7/121

A California sea lions basks in the evening sunlight while resting on a rock in the La Jolla Marine Reserve, one of 11 California marine protected areas (MPAs).

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 8/121

A bod surfer is upended amid the crashing shorebreak at Windansea Beach in La Jolla.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 9/121

A surfer heads in by a fire pit, hammock and palapa at dusk at San Onofre State Beach in San Clemente.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 10/121

Mila Renieri and Diego Merli of Milan, Italy, play on a homemade teeter-totter at San Onofre State Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 11/121

A “no beach access” sign is posted at Dan Blocker Beach scenic viewpoint. The beach is one of several in Malibu that don’t allow public access.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 12/121

RV campers have an ocean view, just across from Pacific Coast Highway at the Malibu Beach RV Park in Malibu.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 13/121

A kayaker checks out the clear waters of Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 14/121

A snorkeler swims around a reef/ rock formation at Crescent Bay, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 15/121

A snorkeler looks for fish at Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 16/121

Garibaldi, the California state fish, swim and feed on rocks at Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 17/121

Small fish swim at the reef at Crescent Bay in Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 18/121

A surfer rides a wave at sunset at “Old Man’s” surf break at San Onofre State Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 19/121

A bodyboarder rides a wave at Crescent Bay, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 20/121

Anders Hamborg rides a wave before his shift working as a Huntington Beach city lifeguard on a warm summer day in Huntington Beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

21/121

A view of the beach through a telescope at Pacific City, a new 31-acre mixed use development in Huntington Beach, also known as Surf City U.S.A.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 22/121

The site of the proposed Banning Ranch development now before the Calif. Coastal Commission.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 23/121

The tide rolls in at twilight at the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) nuclear power plant located on the border of San Diego County and San Clemente.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 24/121

A view of the AES Huntington Beach Generating Station, where an ocean water intake pipe is located that uses a technique of once-through cooling that is harmful to marine life scheduled to be phased out by 2020. The California Coastal Commission is holding a hearing on the proposed Poseidon Huntington beach Desalination project September 7/8. Poseidon would operate next to the AES power plant and use it’s ocean water intake pipe.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 25/121

A dolphin leaps out of the water with a view of south Laguna Beach in the background on Aug. 12, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 26/121

A pod of dolphins leaps out of the water with a view of south Laguna Beach in the background on Aug. 12, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 27/121

The Spirit of Dana Point, a traditionally built replica of a 1770s privateer schooner used during the American Revolution, takes a sunset cruise past The Headlands, center, and The Strand at Headlands development, left, in Dana Point. The Coastal Commission approved the 121-acre development known as The Strand at Headlands in 2004, but only after a decades-long fight between conservationists and the developer.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 28/121

The orange glow of the setting sun shines through palm trees on a warm summer evening in Heisler Park, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 29/121

Beach combers enjoy a warm summer evening exploring the ocean and coastline of Main Beach, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 30/121

Couples enjoy a sunset on a warm summer evening in Heisler Park, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 31/121

Beach combers are silhouetted by the sky’s glow while exploring the rocks at sunset on a warm summer evening in Heisler Park, Laguna Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 32/121

Children run along the beach at twilight near the Crystal Cove Beach Cottages.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 33/121

The sun sets over the Crystal Cove Beach Cottages in Newport Beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

34/121

Kayakers take a scenic cruise in Monterey Bay on a summer day in Monterey. In the background, sand dunes line the coast where the proposed hotel and condominium Monterey Bay Shores development in Sand City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 35/121

Isabella, 9, and Holden, 7, roast marshmallows over a beach fire with their parents, Steve and Amy Knuff of Aliso Viejo at twilight at Crystal Cove Beach Cottages.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 36/121

Incoming tide rolls onto the beach at twilight at Crystal Cove Beach Cottages. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

37/121

A photographer captures the sunset over the ocean in Rancho Palos Verdes. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

38/121

The Point Vicente Lighthouse illuminates the landscape at twilight in Rancho Palos Verdes. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

39/121

A person climbs up the giant Point Mugu Sand Dune, across from Thornhill Broome Beach State Park in Ventura County.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 40/121

Taylor Geer and Marissa Acosta of Thousand Oaks relax on top of the giant Point Mugu Sand Dune, across from Thornhill Broome Beach State Park in Ventura County. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

41/121

Kids play on a stand-up-paddleboard at Leo Carrillo State Park in Malibu. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

42/121

Vivienne Lee, 7, of Thousand Oaks, jumps across rocks under the arches of a rock formation while watching the tide roll in at twilight at El Matador State Beach in Malibu. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

43/121

Keenan Yoo watches the waves crash at twilight at El Matador State Beach in Malibu. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

44/121

A tidal inlet reflects the surrounding landscape as a couple walk with their dog at twilight along Arroyo Burro Beach County Park in Santa Barbara. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

45/121

A Blue Heron flies over the Naples State Marine Conservation Area. Phil McKenna, president of the Gaviota Coast Conservancy, says the portion down-coast of Point Conception contains approximately 50% of its remaining rural coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 46/121

A man fishes in the ocean at sunset at Arroyo Burro Beach County Park in Santa Barbara.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 47/121

A deer takes a break from grazing to look out over the meadow in Cambria.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 48/121

A man walking his dog is viewed underneath a Cypress tree canopy over the beach boardwalk along Moonstone Beach in Cambria.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 49/121

A surfer rides a wave near a rock formation in Morro Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 50/121

The sun, filtered by forest fire ash and fog, goes down at the Morro Bay Marina, with a view of Morro Rock and sailboats.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 51/121

Surfers walk down the beach after surfing in front of Morro Rock.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 52/121

A windmill lines an undeveloped stretch of coast along Cayucos’ Estero Bay with Morro Rock visible in the background.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 53/121

A child bundled up in a thick wetsuit, cap and life jacket, skips to the water’s edge with an adult taking them body boarding in Morro Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 54/121

A child toting sand toys heads across the sand dunes at Morro Bay State Park in Morro Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 55/121

The tide fills in between jagged rock and cliff formations at Montaña de Oro State Beach in Los Osos.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 56/121

The tide fills in between jagged rock and cliff formations at Montaña de Oro State Beach in Los Osos.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 57/121

Elephant Seals battle one another on the beach rookery at Piedras Blancas State Marine Reserve, San Simeon.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 58/121

A scenic view of the setting sun shining through the fog along the Big Sur coastline. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

59/121

A scenic view of a waterfall spilling onto the beach at Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Big Sur coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 60/121

A scenic view of an iconic California coastline gem, the Bixby Bridge, Big Sur.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 61/121

Tourists sit together at a lookout point while exploring the Big Sur coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 62/121

A scenic view taken from Rocky Point, looking out over the Big Sur coastline.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 63/121

Elephant Seals gather on the beach rookery at Piedras Blancas State Marine Reserve, San Simeon.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 64/121

Kayakers take a scenic cruise on Monterey Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 65/121

A scenic view of Garrapata State Park in Carmel-by-the-Sea.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 66/121

A view of Carmel Sunset Beach on a summer day.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 67/121

A child climbs a dune on the site of a proposed, nearly 400-unit hotel and condominium development in Sand City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 68/121

A Western snowy plover, a threatened species protected under the Endangered Species Act, stands amid critical habitat at the site of the proposed Monterey Bay Shores condo and hotel development in Sand City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 69/121

Amid fog, Mark Massara, a decades-long coastal steward, surfs in front of Shark Tooth Rock at Martins Beach, where an access gate remains locked despite a judge’s order to landowner Vinod Khosla to to open the private gate and allow public access to the beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 70/121

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez revisits Santa Cruz, where he surfed as a boy.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 71/121

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez surfs in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 72/121

The sun illuminates the incoming tide as a child plays in the water near Twin Lakes State Beach in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 73/121

A harbor seal lets out a yawn while relaxing on the rocks at Pigeon Point Light Station near Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 74/121

A sailor heads out to sea from Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 75/121

A mural on a beach cottage wall at Martins Beach, where an access gate remains locked despite a judge’s order to landowner Vinod Khosla to to open the private gate and allow public access to the beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

76/121

The sun sets as a crew team glides through the water near Lighthouse Point in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 77/121

A tourist takes in the coastline scenery at Pigeon Point Light Station near Santa Cruz. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

78/121

A view of the scenic Pigeon Point Light Station State Historic Park in Pescadero.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 79/121

Sailboats and stand-up-paddle boarders share the water off Lighthouse Point in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 80/121

Ash from a nearby forest fire creates a yellow-hued sky at sunset at Natural Bridges State Beach in Santa Cruz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 81/121

A view of one of California’s most beloved coastal gems: the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco skyline from the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 82/121

An egret searches for breakfast on a foggy morning at Bolinas Lagoon Nature Preserve in Stinson Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 83/121

A family walks across the beach amid the fog at Dunes Beach in Half Moon Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 84/121

A man checking the surf is silhouetted by evening sunshine reflecting off the ocean amid fog at Dunes Beach in Half Moon Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 85/121

Harbor Seals relax in the mud at low tide on a foggy morning at Bolinas Lagoon Nature Preserve in Stinson Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 86/121

A crab crawls through the mud at low tide at Bolinas Lagoon Nature Preserve in Stinson Beach.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 87/121

White pelicans and sea gulls perch on a sand bar in Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 88/121

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez, left, gets a kayak tour through the eel grass from Amy Trainer, right, deputy director California Coastal Protection Network.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 89/121

A coyote hunts for food along the shore in Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 90/121

Tom Baty, a local environmentalist, has a collection of Japanese glass fishing floats he found on the beach over the years. They are used to hold up fishing nets.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 91/121

Tom Baty has been involved in the fight to close the oyster farm on Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 92/121

A harbor seal checks out kayakers in Drakes Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 93/121

Steve Lopez, left, gets a kayak tour from Amy Trainer, in white kayak, Brett Miller and Cicely Muldoon.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 94/121

Remnants of oyster racks are part of a restoration project to remove 470 tons of marine debris and 5 miles of oyster racks in Drakes Estero

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 95/121

Amy Trainer, deputy director California Coastal Protection Network, kayaks past oyster racks in Drakes Estero.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 96/121

Amy Trainer, deputy director California Coastal Protection Network, kayaks past oyster racks in Drakes Estero.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 97/121

The tide pools at the scenic Shell Beach in Sea Ranch, Calif. Sea Ranch rallied a generation of coastal stewards demanding public access to the rugged and scenic beauty on the Sonoma County coast.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 98/121

A view of flowers overlooking the Pacific Ocean at Bodega Head, Bodega Bay.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 99/121

A blue heron perches on a branch at The Hole in Bodega Head that was meant to hold a nuclear power plant. Photo taken at Bodega Head, Bodega Bay, Calif.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 100/121

A view of the rugged beauty of the Sonoma County coast.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 101/121

Couples take a scenic walk on the beach in Crescent City.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 102/121

The rocky coastline of Shelter Cove.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 103/121

Fog partially obscures the high cliffs of the Lost Coast, where early conservation activists fought development in Shelter Cove.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 104/121

A woman watches the tide roll in on Black Sands Beach in Shelter Cove along the Lost Coast.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 105/121

A woman walks along Black Sands Beach in Shelter Cove.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 106/121

An evening view of the Mendocino County coastline in Northern California.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 107/121

A full moon rises at dusk over the protected Ma-le’l Dunes in Arcata, which contain eight distinct habitats.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 108/121

Sunset illuminates Battery Point Lighthouse and sea stacks in Crescent City on July 18, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

109/121

A surfer heads out at sunset to catch a wave near a sea stack in Crescent City on July 18, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

110/121

Flowers overlooking Enderts Beach near Crescent City on July 19, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

111/121

The Battery Point Lighthouse illuminates the night sky near sea stacks in Crescent City on July 18, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

112/121

A couple walks along the beach at Pelican Bay State Beach after crossing the California border from Oregon on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 113/121

Empty half-acre lots and paved roads are now part of the Lake Earl Wildlife Area on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 114/121

A blue heron lands on a tree branch amid the rich habitat of the south Lake Earl Wildlife Area, which was formerly private Bliss Ranch and is now public land near Crescent City on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 115/121

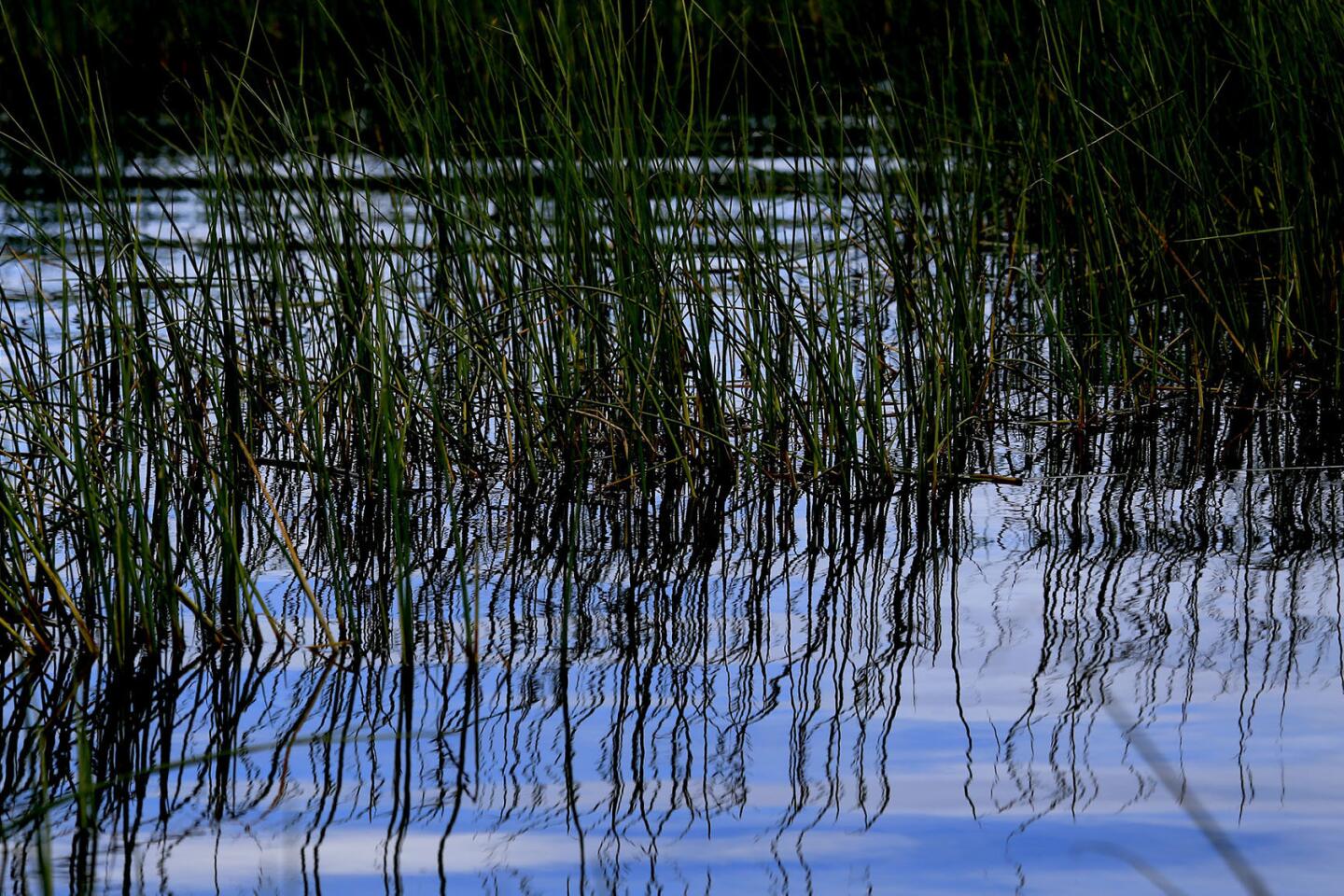

Water ripples among reeds in the near-empty half-acre lots and paved roads that are now part of the Lake Earl Wildlife Area.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 116/121

Sunset illuminates sea stacks and the coastline at False Klamath Cove in Redwood National Park near Crescent City on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 117/121

The sun sets behind trees at False Klamath Cove in Redwood National Park near Crescent City on July 18, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 118/121

A view of the Smith River National Recreation Area in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park on July 19, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

119/121

Times columnist Steve Lopez, right, kayaks with Grant Werschkull, left, co-executive director of the Smith River Alliance, on the Smith River National Recreation Area in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park on July 19, 2016. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

120/121

An elk grazes in the meadow at sunset in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park on July 19, 2016.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 121/121

Patterns formed by the wind and bird footprints in the sand at the Ma-le’l Dunes North, which contains eight different habitats, in Arcata on July 19, 2016. The dunes are highlighted as a victory for the coast after a years-long fight by conservationists to keep off-highway vehicles off the unique sand dunes.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) One hero of the movement was the late Hazel Mitchell. As some tell it, the Tides restaurant waitress — who used to serve Alfred Hitchcock during the filming of “The Birds” — overheard PG&E executives at her table talking about the power plant. Town folk had thought it was going to be a steam plant, but Hazel got a big scoop. It was an atomic power plant, not a steam plant. And it was going to be built smack dab on the San Andreas fault.

Dave Pesonen of the Sierra Club was a persuasive ally against the power plant, Lucy said. She also credits former state Assemblymen Alan Sieroty and John Dunlap for helping form an alliance of coastal stewards. That set the stage for the launch in 1972 of Proposition 20, the California Coastal Initiative, aimed at regulating coastal development.

Developers and industry giants poured money into the campaign against the proposition, far outspending proponents. But as Ocean Foundation senior fellow Richard Charter puts it, the modern environmental movement was ascendant by then.

The Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 had politicized many Californians. Rachel Carson’s 1962 “Silent Spring” sounded the alarm on environmental hazards. The specter of atomic radiation leaks getting into the Sonoma Coast milk supply spooked parents, and no one wanted their seafood contaminated.

On Nov. 7, 1972, Californians went to the polls.

They approved Prop. 20 by 55.2% to 44.8%.

The California Coastal Commission was born, and four years later the Coastal Act — one of the nation’s toughest sets of environmental safeguards — became law.

The act regulates development, requires public access to beaches, and declares that “the permanent protection of the state’s natural and scenic resources is a paramount concern to present and future generations of the state and nation.”

The California coast, Charter said, is “a public miracle” that was protected by ordinary people who saw it as “a global treasure.”

Sea Ranch, in the end, was scaled back considerably and public access to beaches was and still is required. The plans for an atomic power plant were scuttled, leaving behind a giant hole in the ground that became a flourishing fresh water habitat.

Along bluffs overlooking Sonoma County’s boulder-strewn shore, there’s a stretch of the California Coastal Trail named after Bill and Lucy Kortum.

Most of the people who fought for the coast 40-plus years ago are still at it, and concerned about what they see as a disturbing trend by current coastal commissioners to be more open to coastal development than past guardians.

Gov. Jerry Brown signed the Coastal Act into law in 1976 and those fighting for the state’s beaches and coves saw him as an environmental ally, Carpenter said.

But Carpenter is concerned about the governor’s silence on disturbing trends this year at the Coastal Commission.

“My message to him is, ‘Get your religion back,’” said Carpenter, who never lost his own.

He took to heart Bill Kortum’s simple plea:

Never back down or give up.

[email protected]

Twitter: @LATstevelopez

Follow me and Times photographer @alschaben as we head down the coast, and join the conversation at #saveyourcoast

ALSO

Brush fire burns more than 2,500 acres in Santa Clarita area

California’s top court rules in favor of Gov. Brown’s water project

Judge questions private talks between coastal commissioners and developer’s consultants