This story is part of Image issue 12, “Commitment (The Woo Woo Issue),” where we explore why Los Angeles is the land of true believers. Read the whole issue here.)

My studio apartment in West Adams is the closest thing I have to a temple. There’s an accidental shrine to my 20s on the left side of my desk: A neat stack of unpaid bills, undeveloped rolls of film. That jagged slice of amethyst gifted to me by an ex. A year’s worth of photo booth strips and Polaroids and party fliers. A “magic candle” for creativity from House of Intuition next to an almost empty bottle of Agua de Florida. I’ve performed exorcisms for past versions of myself here and prayed for new ones. I could assign sanctity to almost anything that happens in this space, but there is one practice in particular that cements it all: At least once a day, a sweet, warm, pungent aroma fills the air, billowing through my windows, finding its way into every crevice. My daily ritual is burning incense.

As a practice, burning incense has been passed down by various cultures throughout history. The purposes have varied between era and region, but its connection to spirituality has been inextricable throughout: from measuring the passage of time in ancient China, to copal resin smoke filling the sweat lodge ceremonies in Indigenous Mexico, to being an integral part of worship and prayer in South Asian traditions. Some beliefs suggest that the smoke itself can be energetically cleansing, or that when used in meditation, aroma can be a tool to bring us back into ourselves, our senses, our breath. Since I was a teenager, it’s been one of the most tangible ways for me to access spirituality — there’s something special about the lingering smell of burnt perfume it leaves on my hair and clothes, the way in which white smoke curls into itself while burning. Burning incense brings things into sharp focus: Once the smoke clears, whatever problem I have — or the person I want to be — becomes clearer too.

In retrospect, it’s also the ritual itself that’s felt necessary. With any ritual — even the ones that don’t seem inherently spiritual, like drinking coffee alone in the morning or taking a walk around my block at night — the magic lies in the action. I read somewhere that cigarette smokers are just as addicted to the ritual of smoking as they are to the nicotine. I don’t know if this is scientifically true, but the idea resonates with me: There are so few moments left in the world that feel like ours — where we can stretch out time and space. A ritual serves as a small moment of possibility, where if you will it, your bad thoughts might be absolved; you might emerge new again. “We do rituals every day,” says Marlene Vargas, co-founder of L.A. spiritual institution House of Intuition. “But we don’t do it with intention. If and when we start to really learn ritual through intention, that is where the beauty and the magic lies.”

For millennia, incense has served as a portal to this feeling — or a chance at manifesting it. It’s something that hits the olfactory system strongest, activating an innate knowledge within us: We know this smell, on a cellular level. We know, either directly or ancestrally, that it’s connected with something holy. Today, there are a variety of incense makers and vendors selling organic sticks and powders and coils and blends in elegant scents that evoke leather and eucalyptus, while at most liquor stores, you can still find the synthetic classics, like “Sex on the Beach.” In 2022 L.A., incense is as crucial to our daily routines as it was thousands of years ago. It’s not just about lighting a stick and perfuming your home. It’s about the energy behind it. Through the ritual of burning incense, we invite in hope.

The scent meets you out on Crenshaw before you even walk into Taj Mahal Imports, the local outpost for scented body oils, shea butter, Jamaican black castor oil and, yes, rows and rows of handmade incense. They come in long plastic baggies dripping with a mahogany oil that stains your fingers with their spicy fragrances. Novelty scents have names like “Michelle Obama,” “Dolce & Gabbana,” “Paris Hilton,” “Lick Me,” “Patti LaBelle,” “Cashmere” and “Baby Powder.” Around a dozen wooden sticks come in a $1 bag. Looking at the wall of incense names is like looking into a crystal ball of collective references — from pop culture, from group memories of smells, feelings, aspirations — that were ground up and turned into something to be burned.

Similarly, when you duck into Incense Route, a small corner shop at the entrance of the Wholesale Plaza off Los Angeles Street, stacked incense boxes offer chances at love, new clients for your business or a way to block envy from others. There are the labels that claim they’ll usher in good luck and blessings forever; others promise a festive night or to open your third eye. So much of choosing the right incense lies in what you’re looking to will into existence, or be in communion with. Each label is a little manifestation, a special moment that awaits when everything has turned to ash. The most popular scents and blends out there, it seems, serve as a reflection of all of our desires.

At House of Intuition, customers come in search of money, love and healing — in that order. The 10-store chain, which started in Echo Park in 2010, sells all-natural loose incense blends, resins and handmade sticks. Of the blends, there’s Iré Ayé, which mixes patchouli, palo santo, frankincense powder and dragon’s blood, ingredients that together “manifest monetary abundance and encourage a magical rain of riches.” Fe Ocan, a deep red blend of gum arabic, roses, white copal, red sandalwood and amber, “encourages love in all forms.” Iwala “balance[s] both the physical and spiritual body” with gum arabic, sandalwood, lemongrass, orange peel, frankincense and white copal.

Plants are said to hold certain properties themselves, explains Vargas. The resins (fragrant hardened sap from trees) sold at House of Intuition — which include white copal, dragon’s blood, frankincense and myrrh — serve different purposes. “Those are the most traditional incense,” says Vargas. “The ones that have been here thousands of years. They have a lot more longevity to them. However, we don’t use them as often because they are sacred tools.” When doing a cleansing ritual at someone’s home, Vargas will use dragon’s blood to either dispel heaviness or bring in love; she uses white copal to invite spirits back in. Frankincense, the energy of which Vargas likens to a father figure, creates a force field of protection; and myrrh is often seen as a metaphor for Mother Earth because of its grounding effect. Choosing which one to burn is the same as picking up a cash-green incense box that says “Attract money.” “It’s all about the intention,” says Vargas.

You cannot beg a god for forgiveness, but you can be ready when he hints at offering it after a long standoff.

For my 18th birthday, right before I moved out on my own, my older, cooler cousin — who at the time was back in town from traveling the jungles of Mexico — gave me a gift. Inside the bag was a small metal tray, a roll of charcoal disks and a bag of sticky, golden resin I would later learn was copal. She broke it down to me: how I had to heat the charcoal and burn the copal over it, how it was meant to cleanse my space and stimulate my energy. There’s a woodsy headiness to copal. It’s not something you can light and forget about — the energy envelops you; the thick, milky smoke becomes inescapable. When my cousin gave me this set of things, she emphasized that I was participating in a sacred ritual with years of history behind it.

We’ve done this for ages: watch history go up in smoke. Incense has been burned long before our generation (some of the earliest traces go back to ancient Egypt) and likely will be burned long after us. There’s a comfort in not only practicing a tradition we find meaningful but also passing it down to the people we love, who then find their own meaning in it. The ritual may change — and has, depending on historical time frame and culture — but the purpose of ritual remains: to anchor us.

We do rituals every day, whether we realize it or not, explains Alex Naranjo, the other co-owner of House of Intuition. Something she’s turned into a spiritual practice after a year of difficult losses is her morning shower. Water is the element of emotion, after all. Naranjo imagines it as not only a physical wash but an emotional one, the heaviness or depression spiraling down the drain. In this space, Naranjo allows herself to cry. The water coming out of the showerhead serves as an example and a metaphor. Releasing allows her to better connect with her mother, whom she recently lost, or her dog Jackson, who died last month. “It brings me a sense of comfort, like I’m connecting with somebody that I love,” Naranjo says. “It doesn’t have to be this big drawn-out ritual — small things that we do on a day-to-day basis can turn into something meaningful because it’s carried out with intention.”

My own incense ritual always has the same beginning and the same objective. At the center is me, feeling too small in a world so inexplicably big, trying to grasp something that is none of my business (life, existence) and searching for a sense of delusional control. I’ll clean my apartment first — wash the dishes, make my bed, wipe down surfaces, water my plants — and only when I’m done do I scan my options. The growing collection of scents on my coffee table offers up an accurate snapshot of my subconscious wants and needs: “Money Matrix,” “Anti-Stress,” “Super Hit,” which “helps reduce the negative and increase the positive aspects of all zodiac signs.” I grab one of the long sticks, put the wooden end between my teeth and light it with my lime-green lighter like a joint. I take the stick out of my mouth, blow out the flame, place it in the cheap, wooden incense holder I got from Santee Alley and take a deep breath. Now I can really begin or end my day.

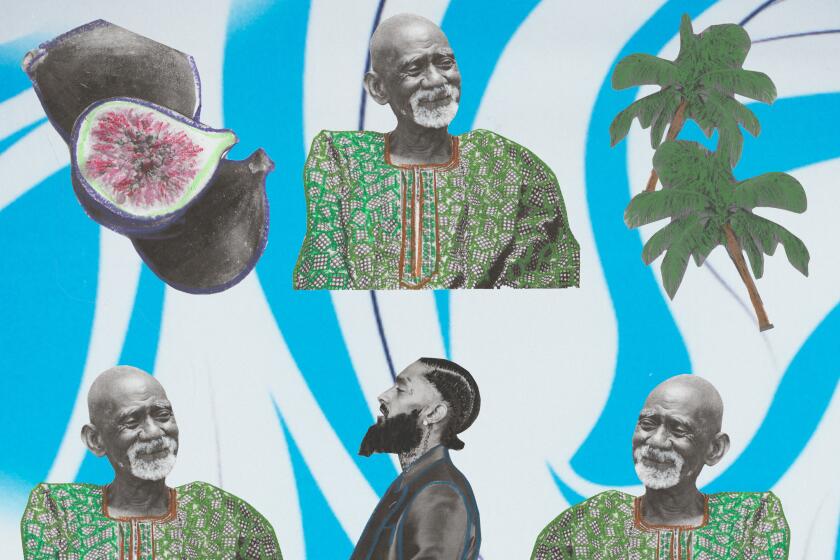

Even in his final act, the legendary scholar and theorist does not mince words. He sees an L.A. that is decaying from the bottom up.

My apartment has an arched doorway, which somehow seems symbolic. Crossing it feels like crossing into a sacred space — reflection and forgiveness and revelation happen here. I break myself down and build myself back up here. The leftover smell hits me first: warm ash, charred flowers, sappy trees and sandalwood. It smells like years’ worth of incense that was burned trying to manifest love, happiness and success.

“It takes you back to that memory of being in a space of prayer,” Vargas says of incense. “It takes you in that sense of sacredness, of when we walked into a space that we believed with holy faith that God existed in. Burning incense makes me think of those moments.”

When I light one in here, as the golden rush of evening or morning light beams through the blinds, revealing the swirling streams of smoke dancing toward the ceiling, it feels like seeing some version of the divine.

More stories from Image