This story is part of Image issue 5, “Reverence,” an exploration of how L.A. does beauty. See the full package here.

For centuries art history has upheld ideals and standards around the concept of beauty. Many of these standards have left much to be explored and little to no room for diverse perspectives. It’s not that those perspectives haven’t always existed — they have. Rather, narratives haven’t included those points of view.

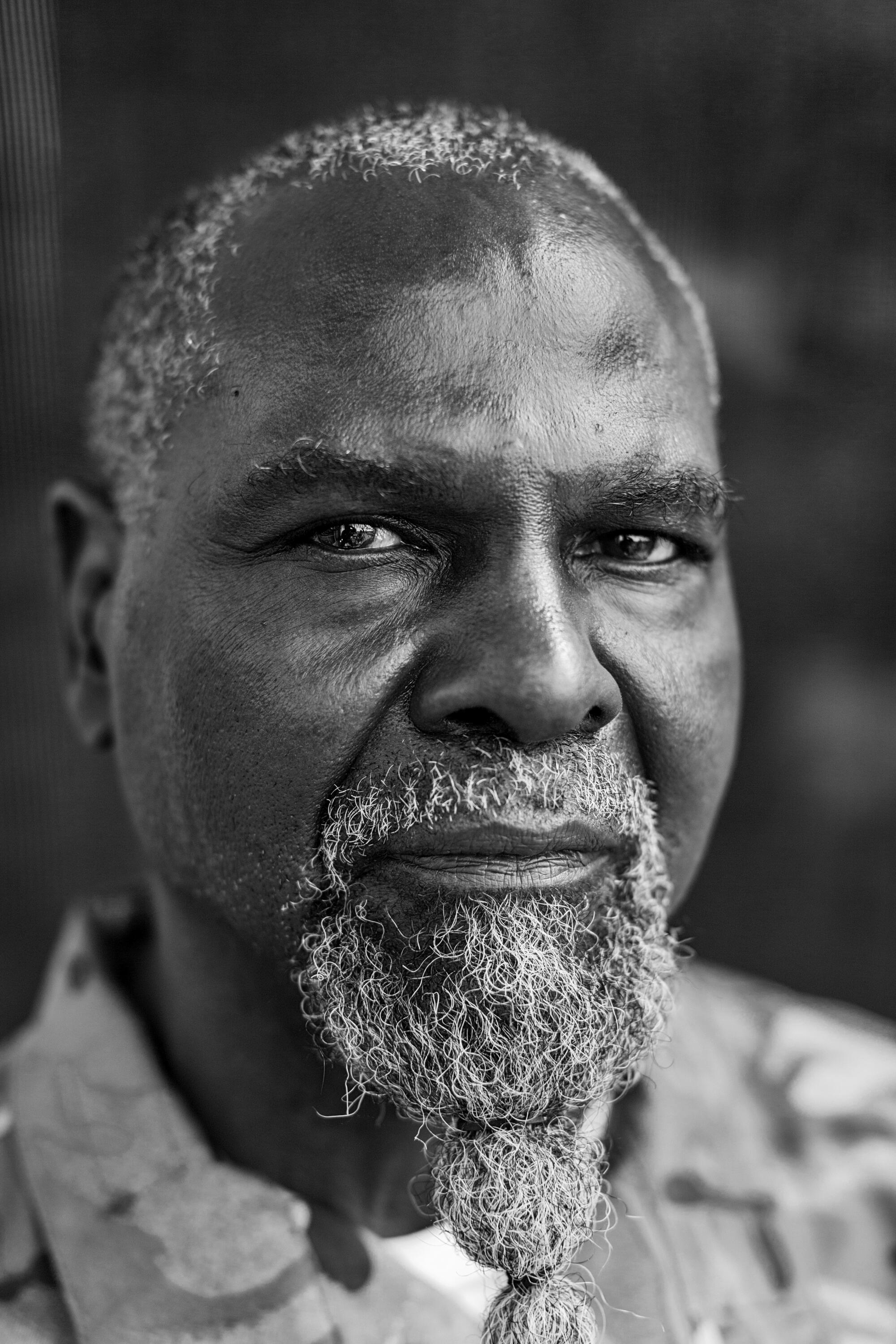

I have had the pleasure to learn and advocate for more revisionist approaches and create space for artists who tell these stories, artists who are revealing beauty in more imaginative ways. One artist who has impacted my understandings of beauty is Fulton Leroy Washington. “Mr. Wash,” as he is affectionately known, was born in the South, raised in Compton and served 21 years in federal prison — plus five years of supervised release — for a crime he says he didn’t commit. He took up portrait painting while incarcerate and, eventually, had his sentence commuted by President Barack Obama. In my co-curated debut exhibition, “Shattered Glass,” which featured the work of more than 40 artists of color, I had the privilege of learning about Mr. Wash’s life and narrative. The oldest artist in the show, his presence was warm and wise.

Recently we reconnected. He shared with me his perspective on his harrowing and extraordinary journey, his work and how he still makes time to admire the beauty in his life when so many events — his encounter with Drake, for instance — easily could have distracted him. Throughout this interview Mr. Wash does what he does best — help me to understand the importance of living a life of beauty and defying the odds in order to do so.

AJ Girard: Mr. Wash. I’m glad we could do this. I’m inspired by you. You put your story to the best use for the world. I want to start by asking how life has been for you in the last two, three months.

Mr. Wash: I think the best way to describe it would be a roller coaster. You know how the roller coaster is like, Chicka, chicka, chicka, chicka, chicka. You get to the top. Then it has this little slope — you really don’t know what to expect. And then it starts to go down. And the rush goes from your gut all the way up to your head. And you can’t even scream? Flip that upside down. That’s what my life’s been like for the last couple of months. I feel so blessed and grateful. This is a new life, a new lane of life, a new level of life for me, and I truly am embracing it.

I’ll be 67 years old. I don’t have as much life in front of me. So whatever the world have to offer me to help me with my life. They need to give it to me now. Because I don’t have a lot of time.

Image Reverence stories

Julissa James unpacks the art of putting someone’s face on your body

Dave Schilling learns what it means to be beautiful in Comme Des Garçons

Jean Chen Ho explores grief through IG thirst traps

Darian Symoné Harvin dives deep into sideburn style

Texas Isaiah shows how photography doesn’t have to perpetuate visual violence

AG: That’s perspective. I feel like when we come together, we often just talk about how it was to grow up — especially where we come from. What was life growing up for you?

MW: I was born in Tallulah, Louisiana. I’m the last person in my family to be born on the plantation…

AG: I didn’t know that.

MW: A lot of people don’t know. I didn’t know until I got out of federal prison. You have to have a birth certificate to get out. And I had never saw mine. When my family got my birth certificate sent to the prison, they handed it to the warden and he said, “I think you need to look at this.”

Anyway, life for me was one of the basic challenges most African Americans have. We lived in poverty. We had hardly any income. I lived in Watts in the [Nickerson Gardens] housing projects. I had to live through the 1965 Watts riots. During that time, it was almost like being in prison. You had the military sent to your door to make sure that you belonged in the building. At the same time, it was very liberating in the sense that there was an opportunity in that community to have things that you never could have before.

We come from a family that learns how to fix things. I’ve seen the work that went into taking damaged things and making them new again. I remember my mom got a job at the Mattel toy factory, and all the workers there were allowed to get broken toys — things that was damaged for whatever reason. Me and my brother would get together and figure out what can be fixed, modified. Models was a big thing. I spent a lot of my childhood building toys for other people. Once I made the toy, it was no more fun to play with. I’ve made it, so now I want to make something else. It’s kind of the same way with art.

Artists Nikko Hurtado, Arlene Salinas and Steve Butcher take you inside one of the most intimate energy exchanges in the world: tattoo portraiture

AG: I want to hear more about your work as a portrait painter. What got you into portraiture?

MW: The art that we see now is just a combination of everything that I’ve learned in experience. During the ’60s, there was a lot of polio. I didn’t quite understand. But my mom explained that everybody don’t come out the same. It don’t mean that we’re not equal. Where you find your weakness in one part, you find a strength somewhere else. We had a few kids that had polio. My auntie was born without eardrums. She could never hear. Her speech was different than ours. I used to be afraid of her. Then one day my mom got me and brought me to her. We sat down and I was able to look and feel her spirit — see inside her eyes — and see what she was trying to say. Looking for the spirit of a person, rather than the physical attributes of the person, helped me to see a little bit deeper, and to have that understanding. When people come to sit with me while I’m painting and tell me these stories, these visions come, and I try to paint that out.

AG: You’ve touched a lot of people. I want to know more about your Kobe Bryant painting. What sparked that for you?

MW: The loss was just so tragic that I felt Kobe’s spirit. I felt it crying out. I think God compelled me to produce that picture. I was touched by Kobe. I could feel the sadness of his daughter, I could feel the sadness that he must be feeling. When we look at the Kobe piece, “Shattered dreams,” I’ve tried to try to take Kobe’s life, and kind of parallel with my own understanding of my life. I lost my mom while I was in prison, while she was on her way, getting prepared to come to see me. I’m a layer painter, I don’t paint the picture, I paint layers and developed a picture that it comes out and leaves you with that feeling that you can actually feel the person.

AG: Last year was big. You were in “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer and the Huntington, and the Jeffrey Deitch show. You had a lot of situations happening at the same time.

MW: I was really blessed. When I first came home, I walked around with pictures of my artwork. I’m knocking on gallery doors, and I’m knocking on museum doors to say, “Hey, I just got out of prison, and everybody in the prison said that my work should be in a museum or in a gallery.” Everybody pretty much closed the door. “This is not how it works. You have to go and do some yard shows, and then do some parking lot shows and then do some church shows, and then do some community shows. Do this and that.” How did I feel about being in the Hammer and the Huntington — I was super delighted. I can’t understand it. It feels like the blessing of God. That is his hand. It ain’t had nothing to do with me.

AG: You were awarded the Public Recognition Award for your work in “Made in L.A.” What was it like when you got the win?

MW: It really was like when Obama done called, and my lawyers done called, and said, “Hey, you free.” I filed dozens and dozens of motions over the 20 years, and they all got denied. Each time, I built that expectation up that I was gonna win the motion. I was gonna go home. And it never happened. So, when I heard that I won, I was in disbelief.

AG: I feel lucky enough to call you a friend and an artist mentor. But to other people, you’re a kind of legend. I want to talk about the time you broke the internet when you met Drake. How did that come about?

MW: I didn’t know who Drake was.

AG: Oh, wow.

MW: I did not know who Drake was. I had never listened to any of his music until this new album [“Certified Lover Boy”] just came out. It’s funny. He had given me DMs. I didn’t know what the DM thing was …

AG: He fell in the DMs?

MW: I did a commencement speech at UCLA. The day before the speech, I went to a dinner. And they — [the people at the dinner] — was like, “You should put the link to the commencement on your Instagram page so everybody that follows you can link in and watch you doing commencement.” I was like, “That’s a real good idea. I don’t know how to do it. Here.” I give them the phone. And when they open the phone up it’s like 180-something DMs I haven’t answered.

He looked at the phone like, what? He showed it to the crowd, and everybody goes, “Oh, naw! Naw! Naw! Naw!” I’m like, “What’s wrong?” They like, “Man, Drake trying to call you.” I’m like, “I don’t know no Drake.” [And they said,] “You red-faced him!” I’m like, “I don’t know no Drake, and I ain’t red-faced nobody!” One of the guys, Johnny, said: “No, Mr. Wash. Red face is the red-hot emoji. When you don’t answer somebody in a DM” — I now understand is a direct message — “that means just shining them on. It makes them mad.” I said, “Oh, no. OK, well, tell him I’m busy.” They like, “You can’t tell Drake you’re busy. He’s like Michael Jackson. He’s like the top in the world.” I’m like, “Wow. OK. Tell him, ‘My apologies. But I’m busy.’ I’ll get back to him.” Marissa type something in and she handed me the phone back and when she handed it to me it vibrated. Drake answered that quick.

So, anyway, me and Drake — we talked, and he’s a very spiritually grounded person.

AG: I was gonna say … it seemed like you guys really would hit it off because he’s so in touch with himself.

MW: Yeah. He’s a cool person. Drake asked where I stay and I said, “I’m in Compton.” He said, “Cool, ’cause I’m in L.A. Let’s link up.” I gave him the address. And he pulled up, stayed about two or three hours.

AG: It seems like he really admired the work too. He talked about it on social media.

MW: [Drake] told me that his life had been changed forever from that day, from that meeting. So I guess we have touch bases on that again.

I think every spirit in the world — we all need a helping hand. We was designed and built for one to help another. Openly sharing and giving knowledge and experience and guidance. Look, if the human experience goal is this is to continue to live for as long as human humanity can live, we need to do that as a society and not as an individual. That means that if you’re going to grow as a society, share all knowledge, share all interest and let everybody grow. The more you put in, the more you receive.

AJ Girard is an L.A.-based independent curator and cultural strategist who is passionate about the arts and social change. He holds a BA in art history from Howard University and has worked with the Broad Museum, the California African American Museum and, most recently, the Underground Museum. His critically acclaimed show “Shattered Glass,” which he co-curated with Melahn Frierson at Jeffrey Deitch, featured work from 40 international artists of color.