This is part of Image Issue 4, “Image Makers,” a paean to L.A.’s luminaries of style. In this issue, we pay tribute to the people and brands pushing fashion culture in the city forward.

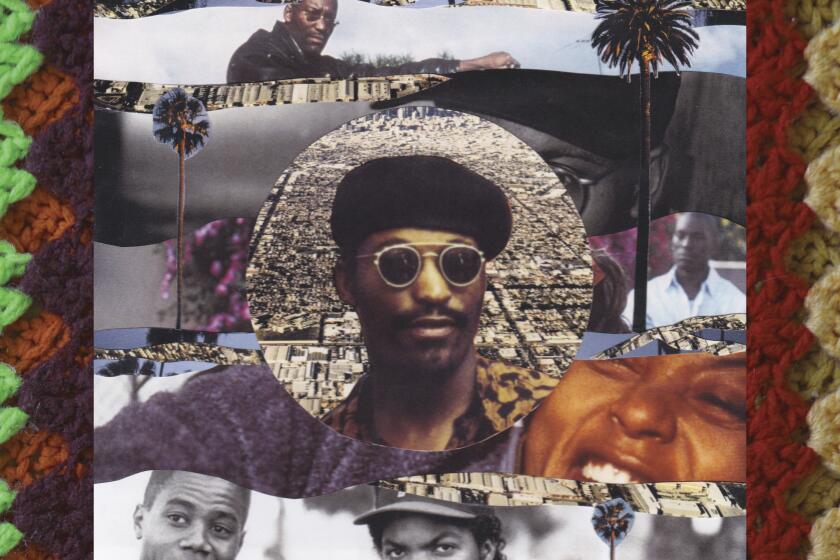

Back in those once-upon-a-time days when everything felt right, there were me and my boys, the lot of us, posing hard for the camera. Our image offers testimony. The year is 2003 and we are on the cusp of graduation, the rest of our lives at our feet. It’s early fall in Southern California, which means movie-blue skies and Friday night football games and weekend hangs at the Bridge. I’m almost done with high school and out of L.A., almost on the way to everything that happens after. But before I can get there, the ambrosia of the past arrives sweet and unexpected.

The filmmaker’s movies were hard and unflinching in their portrayal of Black Los Angeles but really what they are about is our fundamental human enterprise: the grace of feeling.

I hold the photograph tight, my thumb over it, and I return to a before place: those bright and unsettled years of the new millennium. There are nine of us, grouped together just outside the cafeteria windows, posturing like we own the lunch yard, like we have it all. Almost everyone is here: Jonathan and JP and Courtney and Ian and Dimitri and Josh and Armand and Adarious and me. We flex with a fantastic innocence, not yet hardened in the way we pretend to be, our faces conveying baby-smooth toughness.

I find more photos like this — ones that talk, ones that ferry nostalgia of the days I sometimes struggle to remember, of the days that whisper in the crowded room of my memory. The photos spill, spill, spill with color and sound. I hear the chorus of my Los Angeles teenhood: the howl and crack of laughter across lunch tables, the awkward courtship of young bodies in the hallways of Culver City High, the rhythm of my dreams. These memories live somewhere in the before and in the after; they stretch a great distance to reach me, to remind me. The memories are what I make and have already been made by.

The more I sit with them, the clearer they become. I begin to remember who I was then. I see us and everything we longed for. We were seeking an unbreakable cool — we wanted to capture it, to hold on to it for as long as we could, for as long as the freshness of our clothing would allow. In hindsight, the most striking impression from the photograph is how we styled ourselves, adorned in crisp white T-shirts. We wore them with uniform pride. But they weren’t just any white T-shirts. There were rules to the game, of course, ways to finesse a certain look and attitude. To achieve that, we armored ourselves in the locally branded T-shirt of choice — Pro Clubs.

Within L.A.’s fashion hierarchy, a Pro Club T-shirt was par excellence; it reigned supreme. With its form-fitting collar and angelic white coloring, the shirt gave the self — that sometimes static figuration of identity — poetic velocity. A Pro Club was a composition waiting to be inscribed — when draped as it was on the body, especially a body that in the calculus of the city’s codes was told it did not belong, the self was infinite. The self became a glorious figuration. You could be whomever. Pose however. There was no limit. And so we did just that. We stunted. We practiced our bravado. We made ourselves. Over and again, we made ourselves.

::

Pro Clubs began, officially, in 1986, with a man chasing reinvention. For years Young Geun Lee worked at IBM in an administrative role, but he felt it was no longer enough. The 1980s flickered with uncertainty. Lee wanted more, dreamed of better. Anxious for new opportunities, he decided to leave South Korea for good. And so it was decided: He sold his car and his home and traveled to the States, setting roots in Southern California.

Hardship was expected but Lee was steadfast in his goal. He hustled and made connections. By fate or fortune, he fell into the local clothing business. It was relatively simple work at first: He bought T-shirts directly from wholesalers and sold them to the local swap meet purveyors. As business took off, Lee was able to buy a van and rent a small warehouse off Vermont Avenue in Pico-Union. Before long, business came to him.

Image Makers stories

Supervsn is creating streetwear from its highest self

Streetwear gods Kids of Immigrants know love is a long game

Bephies Beauty Supply is redefining community in L.A. streetwear

The Paisaboys let us in on the long-running inside joke behind the gear

Family time with the skate crews of L.A.

The brand that Pro Club would become was not without serendipity. It struck first in 1984, when Young Geun married Casey, a fellow Korean migrant who’d been living in the U.S. since the ’70s. It struck again in 1994. After the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) severed business that Lee had in Mexico — revenue took a 20% hit — the template for Pro Club was dreamed up.

In capable hands, misfortune is a brilliant catalyst. Brian Lee, who today runs the marketing and e-commerce for Pro Club, recounts the dilemma his father faced during those nascent days. “My father was like, ‘What should I do?’” Brian says. The answer was in the form of a solitary item of clothing: a practical, ready-to-wear white T-shirt.

Sartorially, Pro Club T-shirts are not like anything else on the market. The expressive appeal is a design marvel: from the spandex embedded into the collar — one of the secrets to its cozy, idyllic fit — to the philosophy behind fabric density (“thick enough so you can’t see through to the skin”). Shirts are dyed in a special blend, Brian tells me, which he says gives them their luminous “snow white” coloring. “It’s not a creamy white like you see elsewhere. Snow almost has a blue glow to it — that type of vibe.”

Similar to those hazy, newborn days in Los Angeles, Young Geun hustled to perfect the white T-shirt, adjusting the formula as his customers at the Slauson swap meet routinely provided feedback. “It became the shirt that they loved,” Brian says of his dad’s conceptual feat. With connections across the Southland, from downtown L.A. to Torrance, Young Geun was able to place his pristine, low-cost T-shirt in swap meets and independent clothing stores. This happened during L.A.’s unsteady post-rebellion period, during a moment when the city was still tending to its deep wounds, which meant nothing was guaranteed. But the T-shirt now had irrefutable real estate. Suddenly, Pro Clubs were everywhere. Success was not far behind.

Today, the magic of a Pro Club is in its sense of scale: Few affordable white T-shirts have such a thoughtful geometric cut and skillful functionality. Aesthetically speaking, it is in a league of its own — miraculous, alchemical, singular. A Pro Club has no parallel. Add to that its utilitarian use — sizes run the gamut, from small to 5XL tall to 10X — which has given it the kind of charm and accessibility other manufacturers lack.

“We didn’t do things like you’re supposed to. We didn’t do marketing to get where we are. It was all word-of-mouth,” Brian says. “We served markets that other people didn’t want to. We gave them basics — quality basics.”

‘Ceramics has become a means of escape for me — a reprieve from social media, the latest trends and the hype of sneaker releases,’ says artist London James.

::

All cities — all regions — possess style. A city’s identity, I’ve come to realize, is formed in the details we sometimes take for granted: in the mundaneness of our everyday encounters, on the streets that we voyage down our entire lives. The same is true of what we wear. Our clothes speak stories; they tell us who we are. In the daily dress of its people — which is to say, in the look of the collective — there are tales of unease, joy and resilience. It may not seem obvious, but it remains so: In what we wear, in how we style ourselves, we unearth a city’s gorgeous, sometimes forgotten history. It utters. We listen.

Witness: The biting cold of Midwest winters as Chicago OGs shield themselves in thick, sumptuous furs. For New Yorkers, Timberlands and Yankee fitteds remain a notorious, undying staple; they are the beat and bedrock of the city’s pulse. Scuff-free Air Force 1s are a stamp of regional pride for Southerners who will forever favor the drip and attitude of a gold name plate, earlobes dotted in ice. And for a time, during the late ’90s and aughts as the canvas of the city called for new hues of possibility, Pro Clubs suggested an architecture for selfhood for many young Angelenos. White tees came to represent a local kind of pop art — with Lee’s T-shirt at the forefront.

Stylist Charlie Brianna, who grew up off Slauson and Overhill, attended La Tijera Middle School during that time. The prevailing wardrobe among male classmates, she says, was a unifying trend. “The tees were extra-long — to the knees,” she remembers. “If you had on a Pro Club you were fly.” Along with Dickies and hi-top Chucks, Pro Clubs represented an essential look of Black and Latino L.A. youth.

I remember us then; the fulfillment we got in being seen in our Pro Clubs, how alive we felt too. After school at the Fox Hills Mall. Saturdays at the Santa Monica Promenade. The texture of those before days, fresh in our white tees, is loud and palpable. It never mattered where one lived or how they got down because a Pro Club was the common denominator. We wanted to be seen. We wanted to be heard.

Trends are mutable. The fun of fashion is in how we take it on, how we adapt clothes to our bodies, wants and curiosities. “I wore them too,” says Brianna, who garnished her look with hoop earrings. Pro Clubs, she added, were one of the few garments truly emblematic of West Coast aesthetics. “It was a uniform for the OGs of the West Coast. It’s a huge part of L.A. culture. It was the go-to shirt that everyone did their customizing on. Before we knew about wholesale or going to screen printers, you would go to the Slauson swap meet, grab one, and have them airbrush on it or embroider it.”

Brianna is now the personal stylist to rapper YG, for whom she buys a pack of Pro Clubs weekly. “The way he works is, he likes everything regular. With a Pro Club, for him, it’s the quality and the cut. You can dress it up or down. It’s always gonna work.”

As vital as adaptability is to the survival of a given entity — let’s be honest, no one endures the times without a little compromise — what has afforded the Pro Club delicious staying power is its adherence to tradition. “Newer brands try to get fancy and do different things with the weight or threads of white tees, but if you keep it clean and simple, you can’t go wrong,” Brianna tells me. Brian Lee agrees. He says the essence of the T-shirt is in how it straddles high and low culture, how it can fit into any world, satisfy all body types. “I like to think we’re classic,” Lee says. “We’re accessible but still stylish.”

The thing about iconography, especially as it pertains to fashion and personal style, or even as it applies to a place and a people, is how symbols can sometimes feel exclusionary, as if they are not meant for the whole. That’s not the case with Pro Clubs — they subscribe to no one gender, race, religion, sexuality. They speak to the mosaic of who we are and who we have always been.

Pro Clubs were, and in many ways remain, the soundtrack to the city — everybody from Ice Cube and Dom Kennedy to the late Nipsey Hussle has rocked them. “Pro Club T-shirts, whiter than Anglo-Saxons / Make it a 1X tall, crispy with the cotton fashion,” Kendrick Lamar raps on 2010’s “For the Homies,” an unofficial praise song for Pro Clubs. “That’s fashion if you come where I’m from / Compton California, one love to the murder capital under the sun.”

Adds Brianna of the shirt’s all-embracing allure: “The OGs wore them. The gang bangers wore them. Artists wore them. We wore them. They’re universal, everybody wants them. That’s how it became an L.A. staple. They work for everyone.”

What constitutes the perfect fit? The residents of Highland Park, Lincoln Heights, Eagle Rock and other neighborhoods that make up Northeast L.A. seem to have decided once and for all: the skinny jean.

::

In a city historically plagued by racial strife and class divisions, unity can sometimes feel elusive, dangerously slippery. And yet Pro Clubs — the buttery resonance of them, their fundamental core — are all about how they unify. That is what I see most vividly as I look at photographs from my youth. I see us and think about the ways we tried to make sense of our place in the world, armored in our striking white tees, ready for what was ahead.

Across the years, SoCal streetwear brands have unquestionably defined and redefined cool — from Stüssy and OBEY to Fear of God — and through it all, Pro Club has endured with the kind of aptitude and foresight that is rare for legacy companies. Pro Club has remained the heartbeat and the soul, the center to which that Angelenos continually gravitate.

And it’s easy to see why. Los Angeles is a city of transplants, of sprawl. I was born and raised in the city, was made by it, but if I reach back far enough, my story, like that of Young Geun Lee and his family, and perhaps like yours, begins elsewhere. My family migrated west from Texas in the 1930s and settled near 117th and Central Avenue. Over time we found comfort in adjacent corridors. The people, families and stories that make up L.A.’s neighborhoods echo mine — from Inglewood and Venice to View Park, Palms and Watts. We are all from someplace else but found our way, made our way, here. And therein lies the essence of the Pro Club white tee: the insistence of the self. It substantiates — it symphonizes — the I among the we. We wear the shirt with eternal pride because it says, simply: We belong here, among one another, home.

Jason Parham is the founder of literary journal Spook and a senior writer at Wired, where he covers pop culture.