To fix overcrowding in L.A., build more housing, mayoral candidates say

Los Angeles mayoral candidates Rick Caruso and Rep. Karen Bass agree that overcrowded living conditions are at the heart of the region’s housing challenges and a critical gateway to homelessness that needs to be addressed to keep people off the streets.

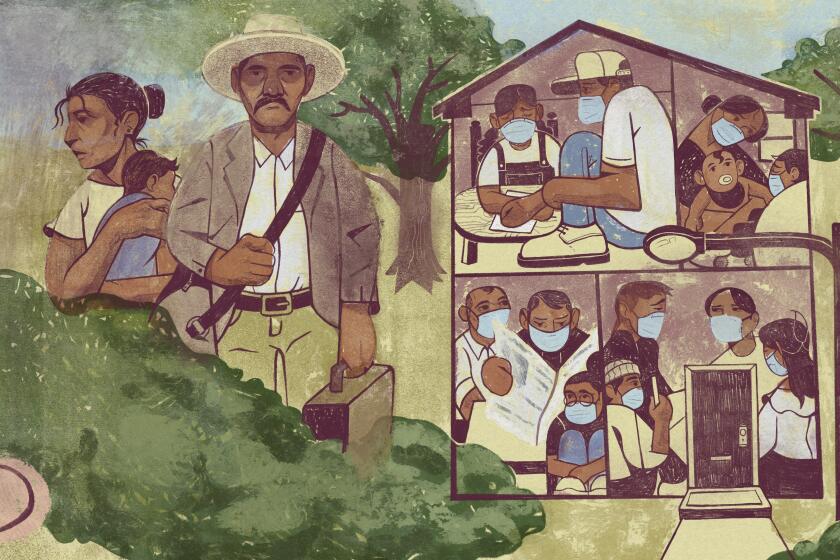

In interviews, the pair offered their insights into tackling overcrowded housing, following a recent Times series that found that L.A.’s leaders over the last century could have alleviated the deplorable living conditions for the region’s poorest residents by building more apartments, taller buildings and public housing. Instead, they fought against such projects with racist policies that made Los Angeles County the most overcrowded in the nation, with more and more people in working-class neighborhoods forced to cram into the existing housing stock.

When the pandemic began, the situation proved fatal. Los Angeles’ most overcrowded neighborhoods have experienced COVID-19 death rates that are at least twice as high as those with ample housing. Residents in Pico-Union, the neighborhood with the most overcrowded housing in L.A., have been 11 times more likely to die from COVID than those living in Manhattan Beach, a community of similar size where only 1% of homes are crowded.

Caruso said it was time for the city to undo zoning changes that emerged during the “slow growth” era from the 1970s that reduced how much developers could build in many neighborhoods.

Those regulations, he said, “don’t even reflect the city anymore. We have to change zoning. We have to build units.”

Bass said the Times reporting revealed the deep failure of policies that concentrated Latino immigrant poverty into neighborhoods that now “cannot take any more people.”

It’s the cruel paradox at the center of Los Angeles housing.

“Your articles make such an important case about why we have to build affordable housing everywhere,” she said. “I honestly think if the good liberal citizens of Los Angeles understood the racial history they would be less inclined to repeat it.”

Both said they want to explore different models of building low-income housing, such as modular backyard homes and micro-housing communities, in addition to traditional projects that rely on tax credits. Price tags in L.A. for those developments have reached as much as $848,000 per unit to build.

“I do think people are coming up with a lot of innovative models that need to be applied,” Bass said.

Caruso, a billionaire developer of high-end shopping malls and apartments, said he wants the city to guarantee loans for low-income housing construction and spread out the costs for building new water, electricity and other infrastructure over time so that housing developers don’t have to shoulder the entire amount up front.

“It’s not complicated,” Caruso said. “There is so much capital in the United States looking for a place to go that if we make it attractive to come in and invest in Los Angeles, we could really start building a lot of units.”

Nevertheless, both candidates believe that many single-family-home neighborhoods — about three-quarters of all residentially zoned land in the city — should remain off-limits for greater density.

Bass pointed to Sherman Oaks, where an influential homeowners association adamantly opposed a new state law that allows duplexes, and in many cases four units, on parcels previously set aside for single-family homes. The association proposed building on commercial strips in the neighborhood instead, which she believed was a fair alternative.

“I would not and I don’t believe you force things on people. But you do involve people and let them come up with their own solutions,” she said. “The attitude has to be that we all have skin in the game and given that we all have skin in the game, how do you deal with it in your neighborhood?”

Caruso said that he would prioritize building along commercial and transit corridors to better connect people to job centers.

“Leave the single-family neighborhoods,” Caruso said. “We’ve got an enormous amount of commercial, industrial — great areas.”

More homes are overcrowded in L.A. than in any other large U.S. county, a Times analysis of census data found — a situation that has endured for three decades.

Eunisses Hernandez, who ousted two-term Councilmember Gil Cedillo in the June primary, will soon represent a district that includes Pico-Union. Forty percent of homes in Pico-Union are overcrowded — defined by the federal government as having more than one person per room — which is more than 13 times the national rate.

Hernandez said she was not surprised reading The Times series. The issues of overcrowding were apparent as she knocked on voters’ doors across the district, with some families unable to open their apartment doors fully because of bunk beds packed inside. Others, she said, recounted how COVID spread rapidly in confined spaces.

The 32-year-old activist knows the housing struggle firsthand. She still lives in the house her mom bought in Highland Park in 1991. That, she said, “is the only reason why I can afford to live here in L.A.” Many of her friends are in similar situations. Others had no choice but to move to the Inland Empire in search of affordability.

Hernandez wants to press developers in the district to increase the amount of low-income housing they include in their buildings.

“We’re one of the richest cities in the world where developers want to come and build here. And so there’s a lot of things we can leverage so that we can push for as many affordable housing units,” she said.

Community activist Eunisses Hernandez unseated L.A. City Councilmember Gil Cedillo in June, but won’t take office until December.

Fixing overcrowding requires focusing on issues beyond building more affordable housing, Hernandez said. She pointed to parents whose incomes largely go to child care, to people with limited employment opportunities, to those barred from getting jobs and housing because of criminal records.

“It’s these different systemic issues that have impacted people, that have put them in a place where they can’t afford housing, where they can’t progress forward,” Hernandez said. “Those are the different symptoms that we want to support. When we think about how we end intergenerational overcrowding in homes, it’s by also providing the people with different social safety nets that will allow for income flexibility, so that they can be able to move out.”

The denser homebuilding and increased public support for low-income tenants needed to fix L.A.’s housing crisis are also needed to solve overcrowding, experts say.

Rep. Norma Torres (D-Pomona) said reading The Times series left her “deeply sad” about the region’s history of housing discrimination that led to overcrowded conditions.

For more than a century, L.A. leaders created a vision of Los Angeles where people could have their own single-family home surrounded by lawns and gardens. But they sold that dream to white people. Others, including Latino immigrants, faced housing segregation, mass eviction through urban renewal and freeway construction, and many were left relegated to living in crowded slum conditions.

Like Hernandez, Torres has seen how high housing costs in wealthier areas of Southern California now have pushed families toward the Inland Empire.

“They see the Inland Empire, the communities that I represent, as the only place where they can bring their L.A. paycheck or their northern Orange County paycheck or northern San Diego County paycheck and can afford to buy a home,” Torres said. “But what does that mean for my constituents?”

In recent decades, Riverside and San Bernardino counties have continued L.A.’s sprawling growth by adding massive new suburban subdivisions. The Inland Empire also has seen a stubborn increase in crowding that has mirrored L.A.’s over the last half-century.

While Los Angeles is the nation’s most crowded large county with more than 11% of homes considered overcrowded, both San Bernardino and Riverside also rank in the top 10 with overcrowding rates more than double the national rate.

Torres said that the federal government needs to coordinate better with cities and counties.

Stuck in an overcrowded apartment in one of L.A.’s most packed neighborhoods, Ruby Gordillo seized a vacant, state-owned home for her family. They may be forced to leave soon.

“We have to be working together in order to get people off the streets, and certainly out of the living conditions that you outlined,” she said.

L.A.’s housing overcrowding problems will remain a pressing concern as public health officials are warning of a new winter wave of COVID-19.

A new academic review analyzing 166 studies worldwide on housing, transit and other environmental factors found that, when examined, overcrowding always was associated with the spread of the virus.

“The effect of overcrowding on the number of cases was completely consistent throughout the literature,” said the review published in the journal Science of the Total Environment. “All of them found overcrowding as a positive and significant predictor of COVID-19 cases.”

Times data reporters Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee and Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.