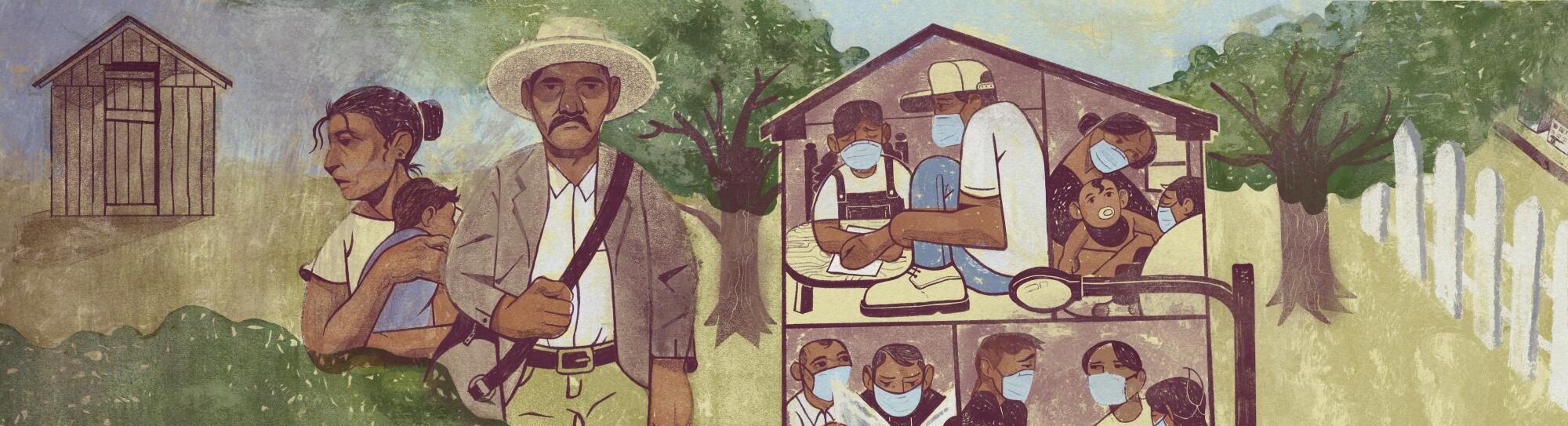

For three decades, Los Angeles has been the most housing-overcrowded large county in the United States. Today, 11% of homes in L.A. County are overcrowded, more than three times the national rate, a Times analysis found.

Packed conditions have long been linked to grisly fires and stunted childhood development, but the dangers have magnified during the COVID-19 pandemic, as studies have shown higher death rates and viral spread in the most overcrowded neighborhoods.

Fixing the problem in Los Angeles, experts say, requires a reversal of the decisions that allowed the region to become so crowded. The answer is more housing, more subsidies for poor renters and more pathways to the middle class for Latino workers and their families, who historically have been most likely to live in overcrowded homes.

More homes are overcrowded in L.A. than in any other large U.S. county, a Times analysis of census data found — a situation that has endured for three decades.

How do we solve overcrowding?

In many ways, experts’ prescriptions of denser home-building and increased public support for low-income tenants don’t look much different from what is needed to alleviate L.A.’s housing affordability challenges in general.

But overcrowding — defined by the federal government as housing with more than one person per room, excluding bathrooms — can be especially vexing, said Dowell Myers, a professor of policy, planning and demography at USC.

Myers’ research has shown that the prevalence of overcrowded housing goes deeper than market fundamentals. Rates of immigration and cultural proclivities of Latino and Asian families toward multigenerational living, among other factors, influence the amount of crowding.

Throughout the 20th century, L.A.’s civic leaders set the conditions for overcrowding to occur: by blaming poor Mexican families for their cramped and disease-ridden living conditions, rejecting low-income housing and, ultimately, shutting down the era of mass home-building. But today’s overcrowding problems date to the 1970s, when a wave of Mexican and Central American immigrants started pouring into the region to work.

Myers said stagnant incomes and expensive housing have kept many Latino families from being able to afford bigger homes long after they first immigrated.

“It’s hard to dig yourself out of the hole and pull yourself up on the ladder when housing costs are rising faster than incomes are rising,” Myers said.

He believes there’s no way out other than building a lot more homes.

Stuck in an overcrowded apartment in one of L.A.’s most packed neighborhoods, Ruby Gordillo seized a vacant, state-owned home for her family. They may be forced to leave soon.

What about income?

That’s the other part of the equation. Few places in the country have L.A.’s combination of such low pay and such high housing costs.

At $80,317 the median family income in L.A. County is slightly less than what it is in Chicago’s Cook County. But Cook County’s home values are nearly 60% lower than those in L.A. County and its rate of overcrowding is similar to the national rate.

L.A.’s economy generates both highly and poorly paid jobs that are dependent upon one another, said Manuel Pastor, a sociology professor at USC and director of the university’s Equity Research Institute. Until the region decides that it’s unacceptable that one set of wages is so low, he said, it will be hard to solve overcrowding.

“It’s a little bit of California and Los Angeles growing up to smell the coffee it’s made,” Pastor said. “Behind every software engineer and creative industry executive and biotechnical scientist is an army of nannies, gardeners and food-service workers, who are also part of our economy. But they’re not thriving in our economy.”

Our story on overcrowded housing involved dozens of interviews and visits to tightly packed apartments where COVID-19 ran rampant.

How might the region change to improve the overcrowding situation?

Changes to the fabric of Los Angeles don’t have to be dramatic to spur a lot more home-building. A forthcoming analysis from researchers at UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation found that modestly increasing limits on the density and height of buildings while reducing parking requirements and permitting fees for apartments and condominiums would boost the city’s housing production by about 14,000 homes a year.

Additionally, suburban communities that have long prohibited growth may have to make room for more people.

A recent study from the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Institute tallied the 10 municipalities in the region with the combination of lowest housing production and highest home values. It found that these areas — Manhattan Beach, Laguna Beach, La Cañada Flintridge and Beverly Hills among them — had roughly twice the income, education level and white population of L.A. as a whole. Officials in these communities have been especially hostile toward denser developments with low-income housing and, in at least one case, mocked the idea of economically and racially integrating.

What progress has been made?

There have been signs that L.A. leaders and residents are becoming more accepting of higher-density development and affordable housing.

Over the last six years, voters in the city and county approved a $1-billion bond measure and a sales tax hike to build housing for homeless residents and provide supportive services. City residents also passed a measure allowing for more development near mass transit. Construction of backyard homes and garage conversions on single-family-home lots, long produced without permits, has zoomed over the last five years as state and city leaders legalized such units. Regional leaders for the first time in recent memory have agreed to plan for growth in L.A. and Orange counties rather than push for more sprawl in the Inland Empire.

L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti championed those measures. In an interview with The Times, he said there has been a significant change in attitude among politicians and the general public from when he first was elected to the L.A. City Council more than two decades ago. Back then, the debate was dominated by concerns about parking, ugly buildings and development that was out of scale with the neighborhood.

“It wasn’t just high-income people; it was high- and low-income people and everything in between who used to say no to development,” Garcetti said.

Today, there’s more openness to growth.

“I think we’ve changed the culture and reflected it,” he said.

How daunting is the task?

Very.

L.A.’s decades of underproduction and depth of need show how hard it will be to provide housing. More than 370,000 families in L.A. County are living in overcrowded conditions. An additional 69,000 people are homeless on any given night. And the cost to build just one unit of low-income housing in L.A. has reached as high as $848,000.

Times data reporters Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee and Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.