‘Coastal Disneyland project’? Groups debate plan to restore Ballona wetlands

A long-awaited state blueprint for rescuing a West Los Angeles ecological refuge created a furor immediately after it was released on Friday, with some environmental activists calling it inadequate and threatening to challenge the proposal in court.

Community and environmental groups long ago chose the Ballona Creek marshlands to make a last stand in a metropolis that has paved over 95% of its wetlands. That’s because there are no other major wetlands left to save from development along the coast of Los Angeles County.

Middle ground is scarce in the fight over the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s final environmental impact report on the proposed large-scale Ballona Wetlands Restoration Project.

“The report doesn’t resolve the human conflicts over these remnant wetlands,” said Jon Christensen, adjunct assistant professor at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. “So the long drawn-out battle over Ballona will continue and little or nothing substantive will happen there for many more years.”

“I respect the various sides of the dispute,” he added. “But with climate change upon us, we desperately need a wetlands management plan in place that provides certain protection for wildlife and access for people and their communities.”

On one side are supporters of the environmental report for the Ballona Restoration Project, which aims to restore fish and wildlife habitat and add nearly 10 miles of bicycle path and foot trails near Marina del Rey. It also would allow tidal flows to penetrate land that has been cut off from the ocean since Marina del Rey was built in the early 1960s and Ballona Creek was lined with concrete.

Opponents fret that dozens of troubled species and much of their habitat would be sacrificed by restoration-related excavation. More than 2 million cubic yards of dredged or fill material would be repositioned on the project site in order to create earthen levees around the northern perimeter of the area and north of Culver Boulevard and allow Ballona Creek to reconnect with its historical flood plain.

Exposing the wetlands to tidal influence from the Pacific Ocean would be a mistake, opponents argue, because higher salinity levels could wipe out flora, fauna and habitat that currently rely on seasonal rains and brackish water.

As expected, the environmental impact report has inflamed the historical feud over the fate of the wetlands, a 600-acre preserve near Culver City and just north of Los Angeles International Airport.

The restoration project is supported by nonprofit environmental groups including Heal the Bay, the Bay Foundation, Friends of Ballona Wetlands and some local community activists, including David Kay, senior manager at Southern California Edison’s environmental department, who lives in nearby Playa Vista.

“While state law mandates that we restore former tidelands for the benefit of fish and wildlife, public access to coastal areas is of paramount importance,” Kay said. “So this project will also focus on trails and bike paths for the 3 million people within 13 miles of the area.”

He added that the process is far from over. “It’ll take several years to get through litigation and then onto certification from agencies including the California Coastal Commission.”

Opponents said they were extremely disappointed in the report, including Marcia Hanscom, executive director of the nonprofit Ballona Institute.

“The Ballona wetlands will be a different kind of an experience after they dig it all up and then put it all back together in a new way,” Hanscom said. “It’ll look like a coastal Disneyland project designed for humans, not the wildlife clinging to existence there.”

In Hanscom’s corner is Walter Lamb, president of the nonprofit Ballona Wetlands Land Trust. The Department of Fish and Wildlife, he said, “left us no alternative but to challenge this remarkably deficient report in court, and we are all but certain to do so.”

Of concern are what Lamb described as “arbitrary and insufficient” protections for federally endangered species such as the Belding’s Savannah sparrows, and inadequate proposals for removing excess pavement from the project site.

Then there is the report’s call for construction of a three-story public parking garage along Fiji Way, adjacent to a large marina, which Lamb says would be “the first such structure ever built in a California ecological reserve.”

The structure would be built and managed by the Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors and provide 320 parking spaces — an increase of 39 spaces from the existing parking lot. Lamb said the Department of Beaches and Harbors wants the parking structure to capitalize on the “overdevelopment of nearby Marina del Rey” and boost the parking fees the department collects.

“That is an illegal and unethical use of space, as we will prove in court,” he said.

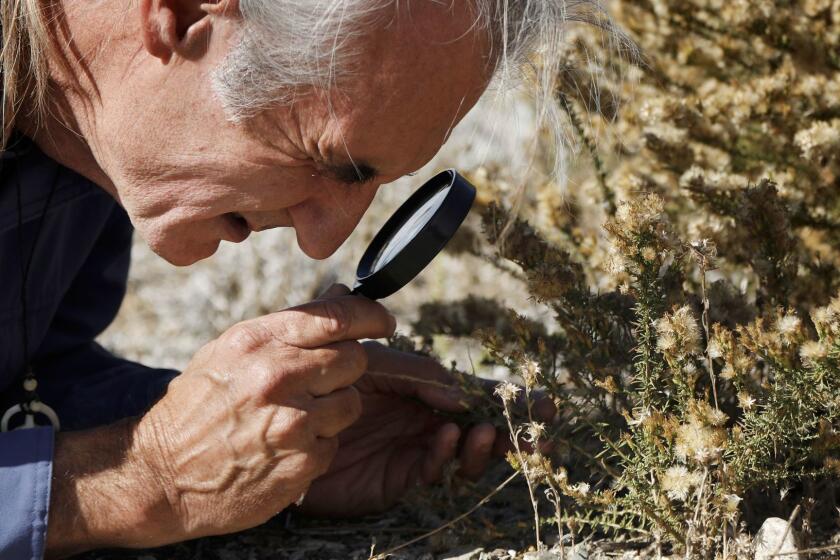

With his long ponytail, floppy sun hat and a peace symbol dangling from his neck, retired federal biologist Robert “Roy” van de Hoek looks like a man bent on saving the environment.

The Ballona wetlands reserve is owned by the state of California and managed by the state Department of Fish and Wildlife. The California Coastal Conservancy, the Bay Foundation and the California State Lands Commission are collaborating in the planning and restoration at the reserve.

Before any restoration and development activities can begin, the project must meet state and federal environmental requirements, and obtain permits from various public entities including the Army Corps of Engineers and the California Coastal Commission.

“I respect that people have strong, passionate feelings about what kind of nature should ultimately exist in this severely altered landscape,” Christensen said. He added that “we need to have a balance between access for people and restoration of nature.”