A rare plant and a renegade environmental activist could derail Ballona Wetlands restoration

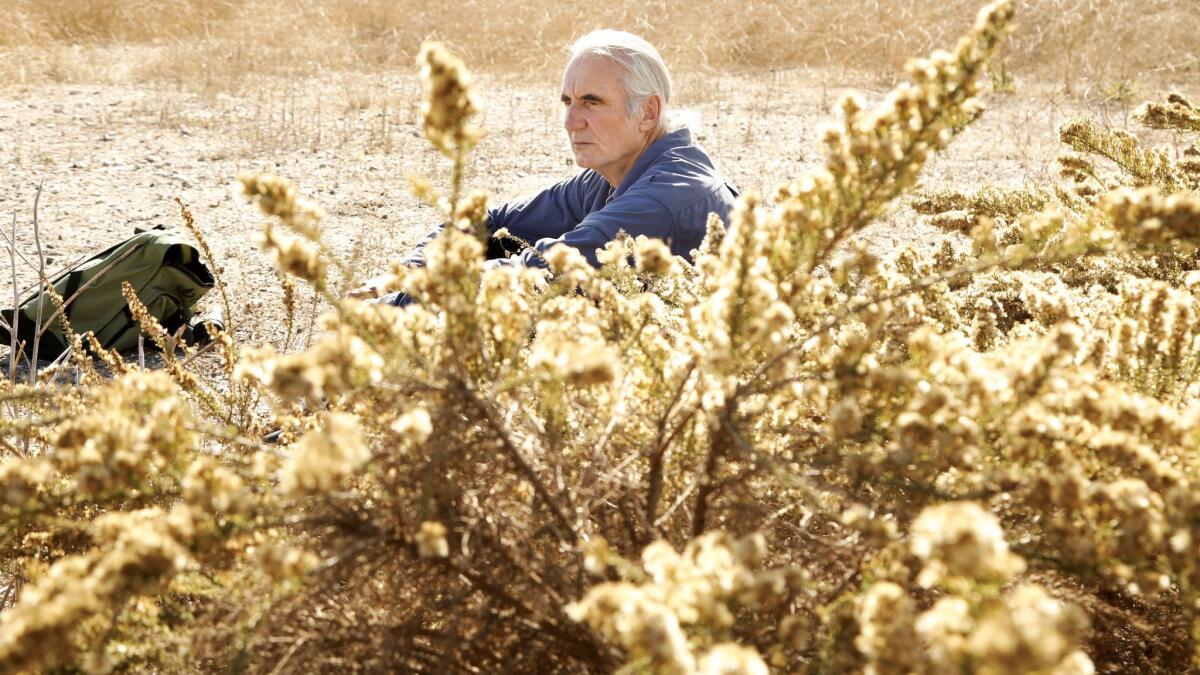

With his long ponytail, floppy sun hat and a peace symbol dangling from his neck, retired federal biologist Robert “Roy” van de Hoek looks like a man bent on saving the environment.

And when he’s crawling through a hole in the fence to sneak into the Ballona Wetlands, it’s clear he’s intent on doing it on his own terms.

He has, after all, released parasitic native plants into the park in a personal strategy to battle flora he considers invasive. And van de Hoek, 60, has faced vandalism charges and a temporary ban from Ballona for taking pruning shears to other plants he believed were crowding out rare native species.

His renegade approach has earned him accolades and adversaries in environmental circles — in part because of his passion, and because sometimes he gets results.

He’s known for eleventh-hour discoveries of rare plants in portions of the wetlands slated for projects he believes will compromise the ecosystem. In 2010, he discovered Orcutt’s yellow pincushions, a dandelion-like plant, sprouting in the center of a $400,000 recreation and wildlife enhancement project that included landscaping and a walkway. Work was temporarily halted while the walkway was redesigned to avoid harming the flowers.

Now, he says he’s discovered a yet another rare plant, this time in the heart of the wetlands where Ballona Creek meets the ocean south of Marina del Rey. And he hopes its presence will bring to a screeching halt a $185-million restoration project proposed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and supported by several leading environmental groups.

Jordan Traverso, a spokeswoman for the department, declined comment “until he provides us with more information.”

In the meantime, van de Hoek’s discovery claim is straining deep passions among more than a dozen groups with environmentalist-sounding names. Some side with van de Hoek and favor a total ban on development in the wetlands. In others, his finding has triggered whispers of a last-minute ploy by an activist who operates under his own rules.

“This new plant is a much bigger deal than the pincushions,” van de Hoek said while visiting the plant Sunday.

To reach it, van de Hoek crawled through a hole in the fence and then made his way along a circuitous route through dense stands of nonnative mustard.

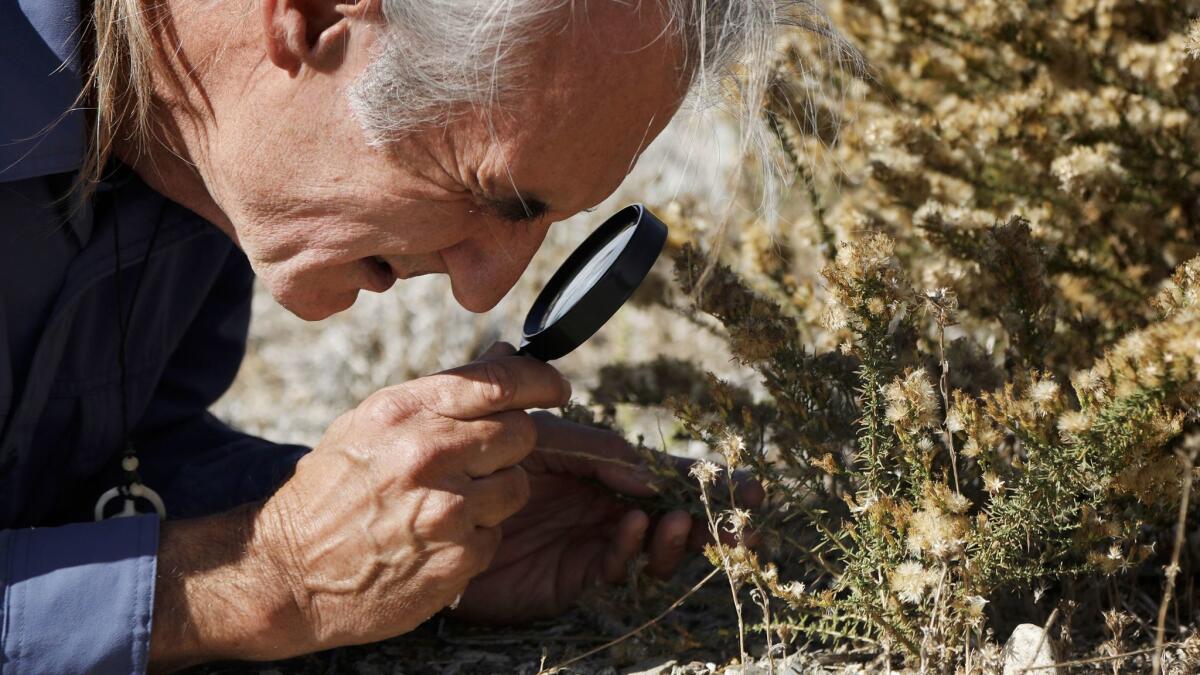

Finally, he came to an abrupt stop and nodded appreciatively toward a clump of bushes about three feet high, 30 feet across and surrounded by pebbly soil. “There it is: Palmer’s goldenbush,” he said with a proud smile.

Dropping to his knees for a closer look at its fuzzy seed pods, he suggested, “This plant could be the snail darter of 2017,” referring to the little fish that brought construction of a multimillion-dollar federal hydroelectric project to a halt in the Tennessee River drainage after its discovery in 1973.

“That’s because it’s growing right where the restoration project calls for construction of a berm 20 feet high,” he said. “It’s not hard to imagine people and schoolkids wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the rallying cry: Save the goldenbush!”

That remains to be seen. In the meantime, he’s inflaming a historic feud over the fate of the wetlands that once covered 2,100 acres.

Once owned by industrialist Howard Hughes, the property is home to ring-necked snakes, great blue herons and the federally endangered El Segundo blue butterfly.

The state paid $139 million in voter-approved bond money in 2003 to buy what was left of the Ballona Wetlands from Playa Capital, the developer of Playa Vista. The deal made the highly degraded expanse of marshes, mud flats and salt pans off limits to development.

Now, the state and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have issued an environmental impact report for creating earthen levees in the area and lowering the land in areas where years of neglect and millions of tons of landfill from the dredging of Marina del Rey in the 1950s curtailed tidal flows and freshwater channels.

Proponents of the wetlands, including van de Hoek, have vowed to fight any bulldozing of the site on grounds it would be harmful to wildlife. Other conservationists believe the plan presents the only hope of rejuvenating natural rhythms of life in the remnant wetlands.

“This discovery, if true, is really good news — I’m a huge fan of biological diversity,” said Shelley Luce, president and chief executive officer of Heal the Bay, which supports the restoration project. “But finding a rare plant does not mean we shouldn’t restore the wetlands.”

“If he’s right, we may decide to move the proposed berm, or the plant — and I can’t say which is preferable,” she added. “But during a restoration project at Malibu Lagoon, for example, we temporarily kept native plants from there in pots for replanting later.”

That kind of talk doesn’t fly with van de Hoek and a group of vocal environmental nonprofits, including Food and Water Watch, Earthrace Conservation and Christians Caring for Creation, strongly opposed to the restoration plan.

“Uproot and replant? No way,” van de Hoek said. “That’s not going to happen.”

In van de Hoek’s corner is Marcia Hanscom, chair of the Sierra Club Angeles Chapter’s Ballona Wetlands Restoration Committee. “We are opposed to massive bulldozing that would destroy homes and food sources for thousands of native animals,” she said, “some of which no longer exist elsewhere on the Los Angeles coast.”

The question now is whether the shrub is actually the rare variety of Palmer’s goldenbush, which the California Native Plant Society says has only been documented in a few sites north of San Diego County: Carbon Canyon in Orange County; the city of Redlands in San Bernardino County; and the Santa Rosa Hills in Riverside County.

Judging from photos of the plant provided by The Times, David Magney, manager of the rare plant program for the California Native Plant Society, withheld judgment. “Without having a specimen in my hands, I can’t rule it out. But without that physical evidence, it’s still a rumor as far as I’m concerned.”

Van de Hoek recently alerted state wildlife authorities of his intention to provide them with specific information about the plant in the coming weeks.

But Andrew Sanders, curator at UC Riverside’s herbarium, said, “Get me a piece of the plant six to 10 inches in length and I’ll give you a determination based on its characteristics within 15 minutes.”

That determination, he said, would be reported to the Consortium of California Herbaria at UC Berkeley, a gateway to information on more than 2 million specimen records.

“Of course,” he added with a chuckle, “someone else might have a different opinion.”

ALSO

Artificial lights are eating away at dark nights — and that’s not a good thing

A Stanford professor didn’t just debate his scientific critics — he sued them for $10 million

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.