Column: Yes, wind turbines kill birds. But fracking is much worse

“Golden eagle’s death sparks shutdown of wind farm.”

“Criminal cases for killing eagles decline as wind turbine dangers grow.”

“Proposed wind farm fuels debate about threats and benefits to migrating birds.”

Those are all recent news headlines. You may have seen similar stories over the years, including from the L.A. Times.

It’s not hard to figure out why there’s so much news coverage. Lots of people love birds, and they’re understandably concerned about giant spinning blades hundreds of feet in the air chopping up their favorite critters. The photos are gruesome.

But should we be even more worried about other types of energy development? Like, for instance, oil and gas drilling?

Absolutely we should, according to a new study.

You're reading Boiling Point

Sammy Roth gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Erik Katovich, an environmental economist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Geneva, had been following all the news coverage of wind power and bird deaths, and he feared it was being “weaponized by those opposed to renewable energy.” A longtime birder himself — he grew up in Minnesota bird-watching with his dad — he wanted to know whether the harm to avian life from wind energy development in California, Iowa and other states was getting blown out of proportion.

So like any good scholar, he ran the numbers.

Katovich turned to data from the National Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, an annual effort dating to 1900 during which tens of thousands of volunteers methodically record bird sightings at consistent locations around the world. Last winter’s count produced more than 36 million sightings of 671 bird species in the United States alone.

In a clever bit of science, Katovich compared the Christmas Bird Count numbers with data showing where wind turbines were built in America’s lower 48 states between 2000 and 2020. He did the same comparison for bird counts and new oil and gas extraction in shale fields — a process defined by the drilling technique known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

His peer-reviewed study was published last month. The conclusions are fascinating.

Katovich found that wind energy development had no statistically significant effect on bird counts, or on the diversity of avian species within five kilometers of a Christmas Bird Count site. Fracking, on the other hand, did have an impact. The drilling of shale oil and gas wells “reduces the total number of birds counted in subsequent years by 15%,” Katovich wrote in the study.

In other words: Oil and gas drilling is worse for birds than wind power. And that’s without even getting into the consequences of burning fossil fuels. Audubon scientists have estimated that nearly two-thirds of North American bird species could go extinct if humanity doesn’t accelerate its transition from planet-warming fuels to climate-friendly energy such as wind and solar.

“The U.S. is now by far the world’s largest oil and gas producer,” Katovich told me. “This is another cost we should consider.”

Fracking may be especially bad for avian life in “important bird areas” identified by Audubon, Katovich found. In those habitats, Christmas Bird Count numbers fell even more dramatically after oil and gas wells were drilled. Species diversity fell too.

Katovich said he doesn’t want to downplay legitimate concerns raised by bird lovers and conservationists about wind farms.

But to my mind, his results are a sign that we pay too much attention to bird-related criticisms of wind energy — probably in part because those criticisms are trumpeted by right-wing provocateurs, including some funded by fossil fuel industry money.

“I consistently find zero effects for the wind turbines,” Katovich said.

For a second opinion on his study, I checked in with Brooke Bateman, the National Audubon Society’s director of climate science, and Nicole Michel, the group’s director of quantitative science. They told me Katovich probably underestimated the harm to birds from wind energy, in part because he included all turbines within five kilometers of Audubon bird count locations. Prior research has found that wind farms are much more likely to kill or injure birds that spend time right near the turbines.

But overall, the new study’s conclusions rang true to the Audubon scientists.

They agreed with Katovich that fracking operations destroy a lot more habitat than wind farms, requiring sprawling networks of paved roads and well pads — not to mention constant truck traffic kicking up dust. Active oil and gas fields are also much busier than wind farms, which tend to quiet down after construction, with lots of undeveloped space between the turbines.

“Oil and gas has a larger footprint, and it has a more dramatic footprint,” said Michel, who’s based in Portland, Ore.

How do we know birds aren’t just avoiding fracking fields, and are doing just fine feeding and nesting elsewhere? If that were the case, Michel said, bird counts would be rising at sites adjacent to oil and gas drilling. But that’s not happening.

“We probably don’t pay enough attention to the impacts of oil and gas,” Bateman said.

I also reached out to Erik Molvar, a Wyoming-based wildlife biologist often critical of big wind and solar farms. I first met him in 2022 while writing about a planned power line that will carry wind energy from Wyoming to Southern California.

Molvar, who leads a conservation group called the Western Watersheds Project, offered several criticisms of the new study.

For one thing, the Audubon bird counts are done by volunteers, meaning the data aren’t perfect. Also, Katovich didn’t analyze the number of birds of each species recorded at each location — a crucial measure of biodiversity, Molvar said via email.

“A bird count that records one cardinal gets exactly the same weight as a count that records 250 cardinals,” he wrote.

Molvar also pointed out that wind farms and fossil fuel extraction can affect birds in different ways. Wind farms are more likely to kill birds than displace them. And some birds are more sensitive to wind farms than others. “Extreme habitat specialists” such as sage grouse — the focus of my first meeting with Molvar — could suffer greatly even as other species get by fine.

When I ran those criticisms past Katovich, he responded gracefully, describing them as “thoughtful and informed” and agreeing that several issues he examined could use further research. He also noted that in the same way his study could be missing some of the damage to bird populations from wind energy, it could be underestimating the harm from oil and gas too.

But let’s not lose track of the big picture, which is the climate crisis.

It’s definitely important that we limit the harm to wildlife from wind turbines, solar farms, transmission lines and other clean energy projects, by putting them in the best places and designing and operating them as safely as possible. But it’s more important to build as many clean energy projects as we can, as fast as we can. There’s no greater threat to animals, plants or humans than a rapidly heating planet. We just wrapped up the hottest year on record, again. This has to end.

Protecting ecosystems from industrial development was the environmental movement’s top priority for decades, and rightfully so. But if that’s still the main framework through which you see the world, I’d encourage you to shift your thinking.

Yes, there’s still loads of untapped potential for small-scale clean energy — solar panels on homes and warehouses and parking lots in particular. But as I’ve written previously, the most in-depth studies have all concluded we won’t be able to ditch fossil fuels in the next decade or two without tons of huge wind and solar farms, and a much larger electric grid than we have today.

That’s why Audubon is working with companies to plan electric-line routes that will limit, but not eliminate, bird deaths. It’s why groups such as the Nature Conservancy are mapping the best sites for solar farms rather than opposing them entirely.

It’s also why journalists should avoid treating bird deaths at wind farms as unforgivable sins, rather than as nasty side effects of renewable energy development that we should work hard to minimize but probably can’t avoid entirely.

As part of his study, Katovich used the International Newsstream database to run a comparison. He found that in 2020, major U.S. news outlets published 173 stories about the effects of wind farms on birds — and just 46 stories on fracking impacts.

I wrote last week that it’s time to see the world through climate-colored goggles. That’s true for the media as much as anyone.

ONE MORE THING

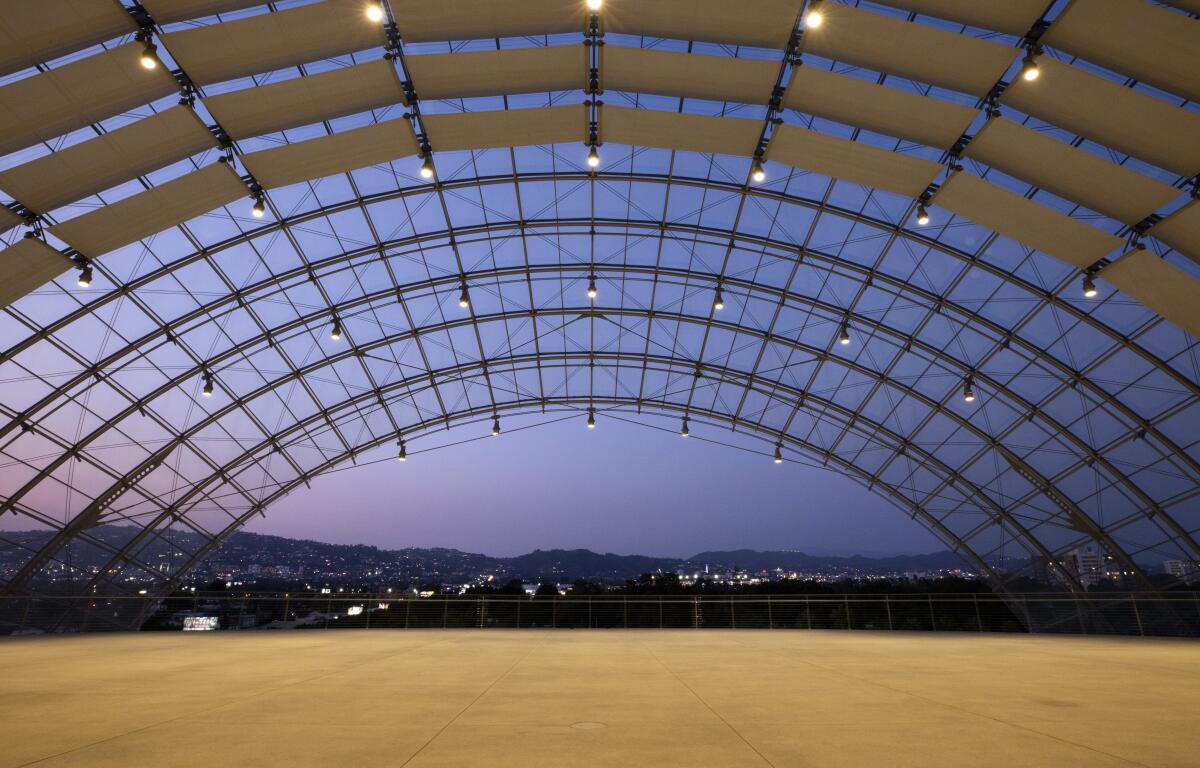

It’s not too late to buy a ticket for this Saturday afternoon’s showing of “The Wave” at L.A.’s Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, part of a series of screenings focused on natural disasters, the climate crisis and how they’re portrayed on screen. As I mentioned last week, I’m hosting a conversation with Chad Nelsen, chief executive of the Surfrider Foundation, after the film.

One update: I’ll be hosting a second conversation the following Saturday, Jan. 20, after an evening screening of “Deep Impact,” the epic 1998 film about a comet hurtling toward Earth. (Morgan Freeman stars as the U.S. president.) This conversation will be with Stephanie Pincetl, a professor at UCLA who leads the university’s California Center for Sustainable Communities.

My L.A. Times colleagues Hayley Smith and Rosanna Xia are moderating conversations, too! Join Rosanna for the 2004 climate change classic “The Day After Tomorrow” the night of Thursday, Jan. 18, when she’ll be joined by UCLA climate scientist Alex Hall. Hayley is doing the Dwayne Johnson earthquake flick “San Andreas” on Friday, Jan. 26, with earthquake scientist Lucy Jones.

Again, you can get your tickets here.

Can’t make it to the Academy Museum but still want to hear me talk? Lord help you. But check out this great video by my L.A. Times colleagues Cody Long and Steve Saldivar. I enjoyed talking with Cody about the climate stories I’m following in 2024.

This column is the latest edition of Boiling Point, an email newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. You can sign up for Boiling Point here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on X.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.