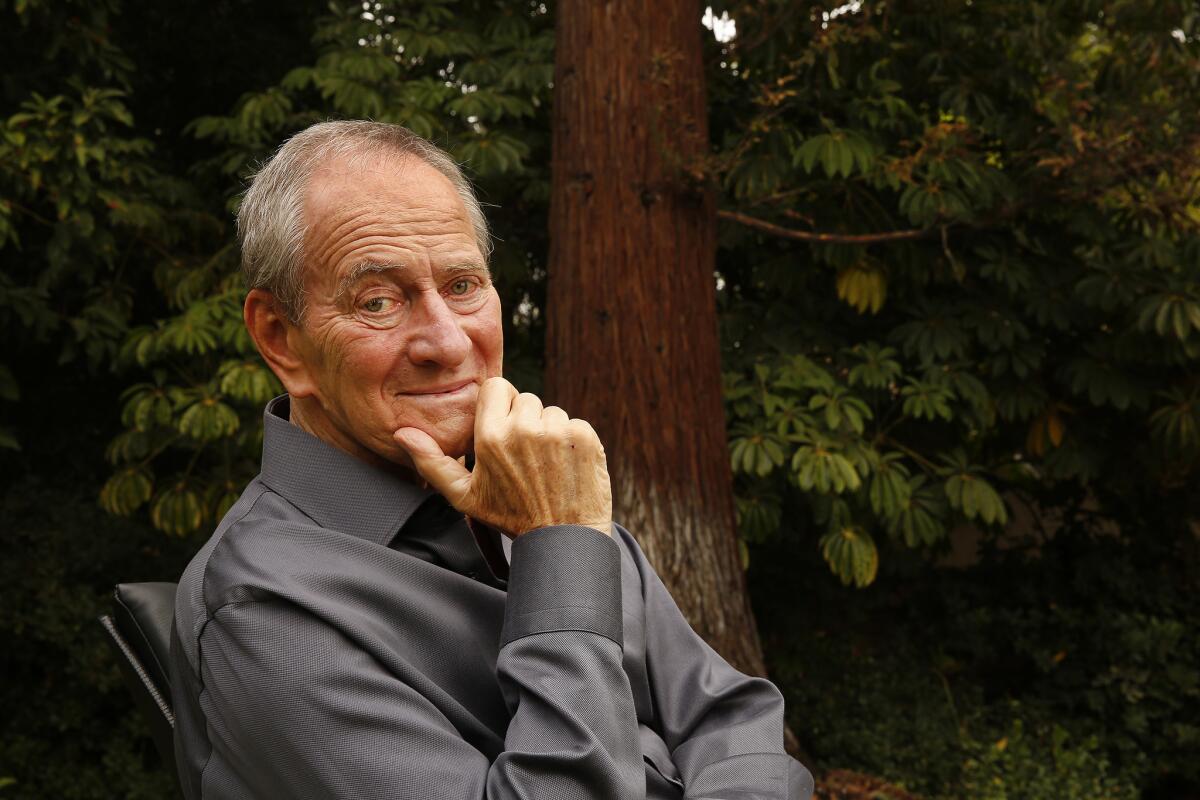

Q&A: Cinematographer Owen Roizman, a 2017 honorary Oscar winner, looks back on his career

Over the course of his career, cinematographer Owen Roizman’s work on such classic films as “The French Connection,” “The Exorcist,” “Network” and “Tootsie” earned him five Academy Award nominations. But Roizman never actually got to take home one of those gold statuettes — until now.

On Saturday, Roizman, 81, will be one of four film artists honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences with an honorary Oscar at this year’s Governors Awards.

On a recent afternoon, the Brooklyn-born Roizman, who has been retired from the movie business since the 1990s, spoke with The Times by phone from his home in Los Angeles about his 25-year career in movies, how the craft of cinematography has changed and why he turned down “Jaws.”

What went through your head when you learned you’d be receiving a Governors Award?

It was a complete surprise. I figured my days had gone and that was it — I wasn’t going to be honored by anybody anymore. I know how tough it is to get that award because I’d been a governor [on the film academy’s board] for nine years and I was involved with many of the sessions where we selected people and voted on them. So it was especially rewarding.

Early in your career, you were really shot out of a cannon, earning the first of your five Oscar nominations in 1972 for only your second film, “The French Connection.” How did that change things for you?

Immediately after “The French Connection,” I got labeled as a gritty New York street photographer, which I thought was very funny because I had never shot anything like the “The French Connection” before that. I got a kick out of that.

My primary goal was always just to serve the story and to tell the story visually the best way I knew how. The thing I’m probably the most proud of in my career is the fact that my five nominations were all for different genres.

But I gravitated toward really liking the look of realism and naturalism. I had that in my mind foremost in every film I ever did, that I wanted it to look real somehow. Even on “The Exorcist,” when [director] Billy [Friedkin] and I talked about it, we thought that the more real it looked, the better the story would come across.

Throughout the ’70s, you worked on so many great films — not only “The French Connection” and “The Exorcist” but “Play It Again, Sam,” “The Heartbreak Kid,” “Three Days of the Condor,” “Network.” We look back on that period as a golden age in movies. Did it feel that way to you at the time?

You know, the honest answer is I had no idea. Each movie that came along was a gift that I was fortunate enough to get that piece of material to work on. I was a bit fussy about what I was going to do most of the time, because I always had commercials to fall back on — that was where I started my career. That allowed me to be choosier about what I was selecting to shoot.

Did you ever turn down anything that you later wished you hadn’t?

The truthful answer to that is I don’t feel like I turned down anything that I regretted turning down. I turned down some great films but for different reasons.

The technology of both the way movies are shot and the way we watch them has changed so much since you started working in Hollywood in the early ’70s. Do you worry that today’s audiences are losing the appreciation for the experience of seeing movies on the big screen?

That part of it bothers me. For someone to watch a movie on their iPad or their phone or whatever, I feel they’re missing out. Then again, some of the TVs that you have at home now for not that much money have amazing pictures.

As far as the process of moviemaking, it’s really the same. It’s just that the tools are so different now.

I remember when my buddy [cinematographer] Roger Deakins shot his first digital film. He had been resisting it forever because he was just a film nut. I asked him, “How did you like it?” And he just looked at me and said, “No more sleepless nights.” Because you can see your work right away. You don’t have to send it to the lab to be developed and printed.

Being nominated five times for an Oscar and never actually winning one before now, did you ever feel like you got numb to it?

You never get numb to it. It’s always exciting. The first time I was nominated, for “The French Connection,” I had never anticipated getting nominated for anything in my life. It was thrilling just to get the nomination. Then, when it came along each time, it surprised me.

I used to joke to my wife, “Well, I guess I fooled them.” And when I was nominated the last time, for “Wyatt Earp,” my wife said, “Guess what? You fooled them again.”

Editor’s note: The Times will profile each of this year’s four honorary Oscar winners — Charles Burnett, Owen Roizman, Donald Sutherland and Agnès Varda — leading up to the Governors Awards on the evening of Nov. 11.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.