From the Archives: George Romero found comfort in zombies, despite reluctance to return to the genre

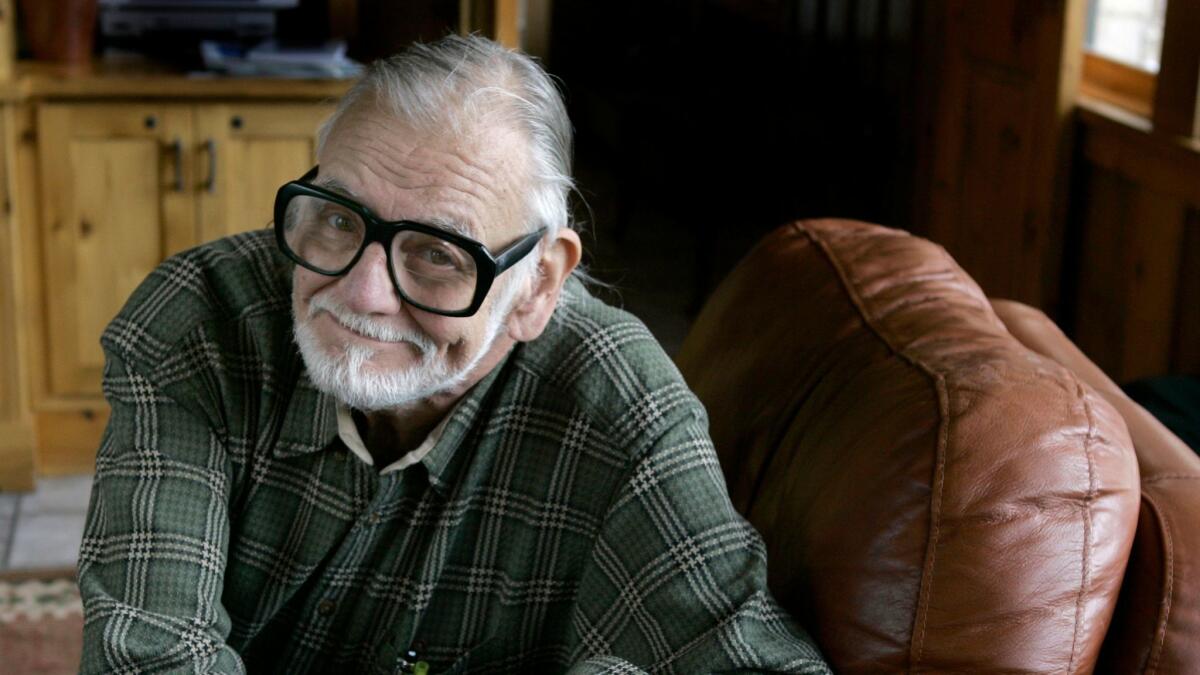

Filmmaker George A. Romero died on July 16, 2017, at 77. Reporter Mark Olsen talked to the influential horror master in 2008. This article ran in The Times on Feb. 13, 2008, with the headline “Undead reckoning.”

Zombie movies might not be the first place one thinks to look for social commentary and reflections on the changing landscape of American culture. Yet for four decades, filmmaker George Romero has used a homegrown framework of down-and-dirty horror pictures as something of a personal journal of his times.

In his latest, “Diary of the Dead,” which will screen tonight at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood before opening in limited release Friday, a group of Pennsylvania film students tries to fight its way back home against a seemingly endless army of back-from-the-dead flesh-eaters. Not surprisingly, the students shoot their adventures -- even picking up an extra camera along the way for cross-cutting -- and their story is presented as “The Death of Death,” a film-within-the-film.

Rather than fall prey to the Digital Age solipsism of, say, “Cloverfield,” Romero’s “Diary” remains sharply perceptive about the ongoing breakdown of traditional media and the way the rise of blogging and broadband culture has, rather than bring people closer together, actually served to isolate us from one another.

More channels, Romero seems to be saying, just means more noise.

“What I like about it is that I feel they are sort of a chronicle,” Romero said of the cumulative effect of his series of five “Dead” pictures: 1968’s “Night of the Living Dead,” 1978’s “Dawn of the Dead,” 1985’s “Day of the Dead,” 2005’s “Land of the Dead” and the latest. “That’s really all. I haven’t felt like I was crusading or campaigning with the films. I don’t feel like I’m preaching or trying to incite or anything else. I’m just trying to reflect my perception of what I see happening out there.”

Reluctant auteur

Romero was raised on E.C. comic books, monster movies and early rock ‘n’ roll. It was with a head full of fantastic imagery and a rambunctious spirit that as a teenager in the Bronx he was arrested for throwing a flaming mannequin from the roof of a building -- a would-be special effect for an early film made with a borrowed camera. Even now at age 68, there is still something of the unprepossessing, gangly kid lookin’ for kicks in his demeanor, albeit with thick-lensed glasses and a graying ponytail.

He remains too something of a reluctant auteur, a filmmaker who almost has to be reconvinced of his own abilities and appeal, despite the fact that the original “Night of the Living Dead,” which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, went from playing drive-ins to the Museum of Modern Art. Quite unexpectedly for Romero, his low-budget debut not only spawned a franchise but became celebrated in such high-tone publications as the French film journal Cahiers du Cinema and is now part of the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry.

“I was resisting at first,” Romero said of the years between the first two films in the series. “I said, I don’t want to be stuck in this genre, I didn’t want to just make another horror film.

“And then when all these people started to write about ‘Night of the Living Dead’ as if it were ‘essential American cinema,’ first of all, I was going to bed puzzled. I didn’t think I was a good filmmaker in that way, and I felt a lot of the high talk of it being a super-political film was an exaggeration at best and maybe not deserved.

“It was only during shooting of the second film,” he continued, that “I realized this could be a shtick, a franchise, and that I had a real obligation, beyond just making a sequel, to do snapshots of the time, and it could become more of a chronicle.”

I was slow to realize what this niche was. How many people have been able to work within an exploitation genre and still express themselves?

— George Romero

Accepting his status

In all the “Dead” films, the deceased come back to life to feed on the flesh of the living. Rather than simply being an example of the overused idea of the “return of the repressed,” Romero pushes the conceit to explore what’s bubbling just beneath the surface of contemporary American culture: race relations and revolutionary tumult in “Night,” rampant consumerist self-obsession in “Dawn,” post-9/11 anxieties in “Land” and the breakdown of traditional institutions, media and communication in “Diary.”

Although the gritty indie aesthetic of “Diary” was a direct reaction to his experiences on “Land” -- a studio effort starring Dennis Hopper, Asia Argento and Simon Baker and the most expensive film in the series -- Romero always has bounced back and forth between mainstream acceptance (a few studio-funded pictures and various fruitless Hollywood production deals) and the scrappier terrain of independent financing and distribution.

“I wanted to do something small,” he explained of “Diary’s” less than $4-million production. “I wanted to see if I had the stamina and the chops to go back and really do a little guerrilla thing. I just wanted to get away.”

It says something of his continuing appeal that he was able to enlist such friends and fans as Wes Craven, Guillermo del Toro, Stephen King, Simon Pegg, Tom Savini and Quentin Tarantino to provide voice-over for the various broadcasts heard throughout “Diary.”

Over the years, Romero has come to a certain detente with his standing in the world, understanding the position of privilege he occupies, feeling at home with his zombie creations, while also perhaps acknowledging a twinge of regret that he is unable to expand beyond the boundaries of genre filmmaking.

“Of course you feel a little hemmed in,” he reflected. “I wish if I had a nice little people story I could actually get taken seriously. But I won’t get taken seriously if I walk in there with that.

“On the other hand, I was slow to realize what this niche was. How many people have been able to work within an exploitation genre and still express themselves, to say something and indicate who they are, how they feel about what’s going on in the world? That’s terrific. That’s a pretty comfortable place to be.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >> »

MORE ON ROMERO:

George Romero: Movies ‘are not perceived as an art form by the industry’ »

George A. Romero, ‘Night of the Living Dead’ creator, dies at 77 »

George Romero’s undead reckoning »

George Romero, knight of the living dead, is a zombie specialist »

George Romero dismisses ‘The Walking Dead’ as ‘soap opera’ »

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.