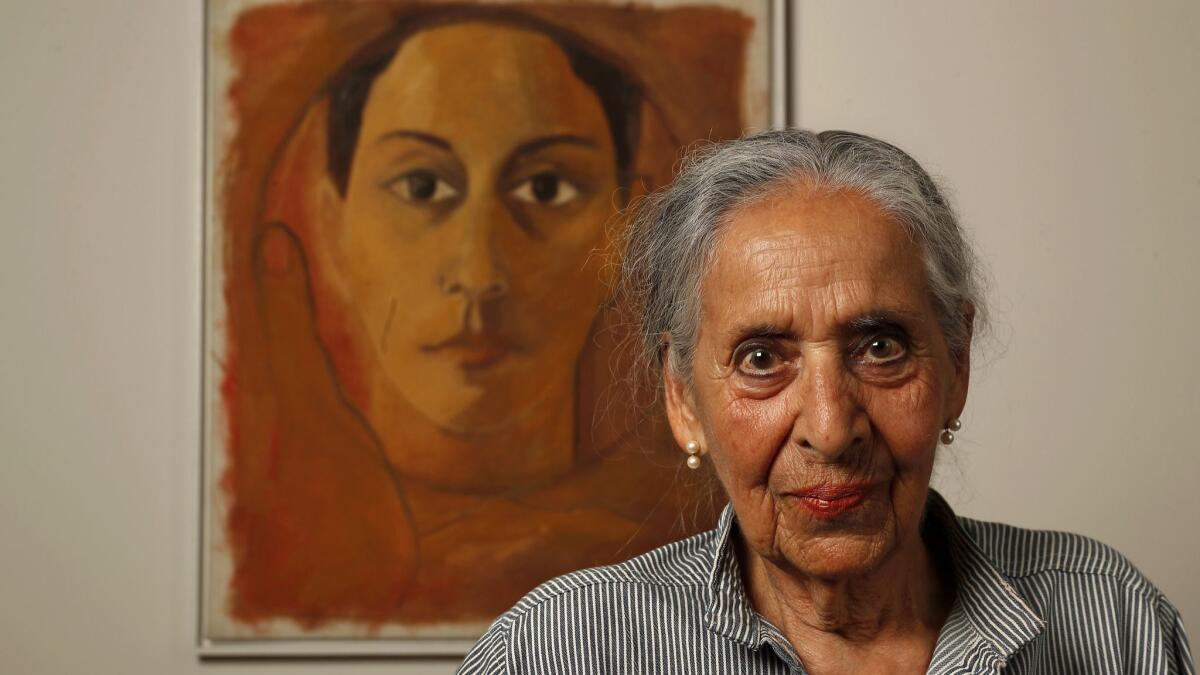

Why Luchita Hurtado at 97 is the hot discovery of the Hammer’s ‘Made in LA’ biennial

At 97, Luchita Hurtado has had enough adventures for three lifetimes. She traipsed around Southern Mexico in the 1940s in search of pre-Columbian archeology. She was pals with sculptor Isamu Noguchi and Mexican modernist Rufino Tamayo. Marcel Duchamp once gave her a foot rub.

“It was the big talk!” she laughs. “All the gossip was that he had massaged my feet.”

Hurtado and her feet are again the big talk — this time for her striking paintings of feet and other parts of the female body against depictions of indigenous rugs, blue sky and sumptuous fruit. They are a large part of the recently opened “Made in L.A.,” the Hammer Museum’s buzzy biennial survey of contemporary art by 32 artists working in Greater Los Angeles.

On a breezy Friday afternoon, the diminutive Hurtado casually strolls into the Hammer’s galleries decked out in a striped smock of her own design. “It’s an original,” she says. “I made this one myself.”

She notes that there are similar ones available for sale in the museum’s gift shop — and proceeds to lead me to the rack where they hang. As we make our way back to the courtyard, she stops and takes a breath. “It is,” she says with wonder, “such a beautiful day.”

If Hurtado’s energy could be bottled as a tonic, it would no doubt sell out.

“She has this completely spiritual energy,” says gallerist Paul Soto, who showed Hurtado’s work in 2016. “Every time I’m with her I’m, like, ‘How can I be more like you?’”

That energy comes through in Hurtado’s works, which have a contemporary feel — so much so that one “Made in L.A.” guest contacted the museum to question the wall text that accompanies some of her paintings. There’s no way, said the visitor, that a painter by the name of Luchita Hurtado could have possibly been born in 1920.

“They left a message saying they really loved the show but they found a typo,” laughs Hammer senior curator Anne Ellegood, who co-curated the exhibition. “They thought Luchita’s birth date was wrong.”

Luisa Amelia Garcia Rodriguez Hurtado was born on Nov. 28, 1920, in Caracas, Venezuela. And over the 97 years that have passed between her birth and the current moment, she has lived at the center of the art world — yet also at its margins.

A peripatetic life took her from South America to New York to Mexico to California — with pit stops in between. In the 1950s, she settled in Los Angeles — Santa Monica, to be exact.

Her paintings have also spanned continents and the 20th century in their subject matter: indigenous patterns, stark Modernism, the surreal and the abstract — bound by a keen understanding of materials. (A series of works rendered in oil stick and bathed in a watery ink have a striking, dappled effect.) But during the near century she has been painting, her work has been largely overshadowed by the men she married — Chilean journalist Daniel de Solar, Austrian artist and theorist Wolfgang Paalen, and for more than 40 years U.S. painter Lee Mullican, a founder of the “Dynaton” group, an influential trio of artists known for their interest in the surreal, the abstract and the cosmic.

While her work has been exhibited sporadically since the 1950s, mostly in group shows, it’s only recently that the art world has taken deeper notice of her paintings. Just in the last two years she’s had two solo exhibitions, but before 2016 her last solo show was back in 1974 at L.A.’s Woman’s Building. You could say that at 97, Hurtado is a fresh face in art.

‘That’s me’

The story of how a virtually unknown, practically centenarian, South American-born painter ended up in one of the art world’s hippest biennials is one of kismet and chance — the result of an unlikely chain of events that began roughly three years ago.

That was when curators cataloging Mullican’s estate began to unearth some curious works. Studio director Ryan Good says he kept stumbling into drawings and paintings that clearly had been made by someone other than Mullican — totemic figures, pulsing abstract patterns, sensuous drawings of plants, most bearing the initials “L.H.”

“So I asked Luchita, ‘Who is L.H.?’” he says. “She was, like, ‘That’s me.’”

Good says he was astonished. Hurtado went by the name “Luchita Mullican,” so he was unaware that the initials might refer to her. And then there was the abundance of her production.

“I don’t think even the family was aware of the breadth of it,” he says. “She has always been making art.”

Hurtado’s work was multicultural before multicultural was cool.

— Christopher Knight, Los Angeles Times art critic

In fact, art is something that Hurtado has quietly devoted herself to since she attended Washington Irving High School in downtown Manhattan in the 1930s. It’s a practice she maintained regardless of where life has taken her, religiously carving out time to paint — principally at night, when she could work undisturbed.

“There is always time to paint,” she says with determination. “Plus, my children slept the night through.”

After stumbling into Hurtado’s work, Good took samples of it to various dealers, who admired her art — but none enough to give her a show. That was until Soto at Park View gallery (since renamed Park View / Paul Soto) caught sight of snaps on the cellphone of a curator from Mullican’s studio.

“I was, like, ‘These are incredible,’” recalls Soto. “I was surprised nobody was taking them seriously.”

In November of 2016, Hurtado had an exhibition at Park View featuring abstract works from the 1940s and ’50s. The show sold out — and drew the eye of Times art critic Christopher Knight.

“Her drawings’ loosely Surrealist forms recall dense pictographs from a variety of cultures, ancient and modern,” he wrote in a review. “Hurtado’s work was multicultural before multicultural was cool.”

The exhibition also caught the eye of Ellegood at the Hammer, co-curator of “Made in L.A.” — who had once previously met Hurtado through her son, artist Matt Mullican.

“Once I saw the show, I went to the studio,” she says. “I wanted to know more.”

Hurtado soon became one of the 32 Los Angeles artists to be featured in the 2018 iteration of “Made in L.A.”

“It means a great deal to me, absolutely,” says Hurtado of being chosen. “I’m delighted to be here.”

A universe of artists

Getting to this moment has been a remarkable journey.

Hurtado is the daughter of a seamstress who immigrated to the U.S. from Venezuela at the age of 8, settling in Inwood, at the northern tip of Manhattan, where, she notes, “all the South Americans lived.” She fell in love with art in high school — where she secretly studied the subject instead of taking sewing, as demanded by her mother (a decision her mom didn’t discover until graduation).

But a career in the arts was not in the cards for Hurtado — at least not immediately. Shortly after graduating, she married Del Solar, a journalist she met through a group that supported anti-fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

“He was a very mean man,” Hurtado says of Del Solar without bitterness. “He abandoned me with two children … for this other woman that he also abandoned when she had two children.”

But Del Solar introduced her to a universe of artists who would shape the course of her life. There was Tamayo, a good friend, who taught at a Manhattan prep school and would often stay with the couple and paint in their kitchen.

“He was fun to be with,” Hurtado says of Tamayo. “A bit of a Casanova. He would call me and he’d say, ‘Mana’ — he called me Mana — ‘please there’s this gorgeous woman who is waiting for a message from me.’ She happened to be married, of course. So I would bring this gorgeous person a message. Who knows what was in those messages!”

And there was Noguchi, the Japanese American sculptor she met shortly after he’d emerged from a World War II internment camp in Arizona. “That was terrible,” she remarks. “They were all put in a terrible place.”

The charismatic sculptor — “he was so popular with everybody,” says Hurtado — ended up connecting her with myriad other intellectuals, including Hurtado’s second husband, Austrian artist and theorist Paalen, who, with Mullican, was one of the founders of Dynaton.

On a whim, she accompanied Paalen to Mexico to see newly uncovered Olmec heads at La Venta. “That was my first date with Paalen,” she says with a smile. “We married a week after we met. It was very impulsive.”

Hurtado soon relocated with her two children to Mexico. For the artist, this was a “very bohemian” time. She and Paalen traveled back and forth between the U.S. and Mexico and associated with a who’s who of artists and writers from Latin America, Europe and the United States. In New York, she became acquainted with Duchamp, who at a casual gathering held at a friend’s home started rubbing her feet.

“I was sitting on this double seat … and Marcel came and sat next to me,” she says. “He was just on the side massaging my feet.” He was a friend, she adds with a laugh. But “the people, they all loved to gossip.”

The untimely death of her son Pablo del Solar ultimately put an end to her marriage. Paalen didn’t want to have children; Hurtado did. She made her way back to the U.S. — to California — where she and Mullican eventually married.

Throughout all of this, Hurtado painted — in improvised spaces often carved out from one of her husbands’ studios. But her work was infrequently seen in gallery settings.

“She very much has had the life of an artist — but without the exhibition history,” Ellegood says. “She was in this active community of artists in every city she lived in. But I think she felt that being a woman of her generation, she felt she had other responsibilities.”

The work on view at the Hammer comes from a key period in Hurtado’s life: the late 1960s and ’70s, when her two children with Mullican — Matt and John Mullican, the latter a filmmaker — were grown and she could take more time to paint. Plus, it was a moment when, for the first time in her life, she had her own dedicated studio space.

“That’s where it began,” Hurtado says.

The paintings on view at the museum, from a pair of related series that feature fragments of the female body — often shown from the perspective of a woman gazing down at her own nude form — feel slightly magical. In “Encounter,” a work from 1971, several pairs of feet and a trio of apples appear to float over a bright geometric pattern.

“When you think of them as works from the 1970s, you can imagine how meaningful they were at that time in terms of female artists taking back the ability to represent their own bodies and shifting the so-called male gaze,” Ellegood says. But the work, she notes, also remains “fresh” and “in the moment.”

Hurtado says that over the course of her life she has been less preoccupied with style or schools of thought than in capturing what was important to her at any given moment.

“It’s kind of a diary for me,” she says. “In a way, it’s what I’m living. It’s a diary of what I know.”

It’s a diary to which she is still adding entries. Hurtado, at the age of 97, is still making work.

“I’m not done here yet,” she says with a wry smile. “There is still life in this old horse.”

“Made in L.A. 2018”

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Through Sept. 2. Also, Luchita Hurtado in conversation with Andrianna Campbell at 1 p.m. July 15, and painter Eamon Ore-Giron on the work of Hurtado, at 6 p.m. Aug. 28

Info: hammer.ucla.edu

ALSO

Luchita Hurtado abstract artworks mix cultures like colors, to rousing effect

‘Made in L.A. 2018’: Why the Hammer biennial is the right show for disturbing times

Ann Philbin and the art of the provocative are thriving at the Hammer Museum

The women at the helm of 2018’s Venice Architecture Biennale and the unexpected generosity of design

Seven of the most intriguing national pavilions to see at the Venice Architecture Biennale

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.