Julian Wasser elevated the adage of “right place, right time” to an art form. As a photographer for Time magazine in the Los Angeles of the 1960s and ‘70s, he knew what to do with his good luck.

Wasser, 89, died of natural causes on Feb. 8, according to his daughter, Alexi Celine Wasser, leaving behind a legacy of historically important images obtained through a combination of timing, savvy and personal charisma. He was a legend of sorts for his rangy, stylish looks and a hard-boiled wit that appealed to celebrities, musicians and artists. And he became something of a celebrity himself with his notorious staged 1963 picture of the Dada artist Marcel Duchamp playing chess with the completely nude writer Eve Babitz at the Pasadena Art Museum. That picture inspired last year’s KCET documentary, “Duchamp Comes to Pasadena.”

Eve Babitz, the author known for chronicles of L.A. drawn largely from her life, died last week at 78. See our full coverage past and present

For the record:

4:16 p.m. Feb. 12, 2023An earlier version of this story included a photo caption that cited Linda McCartney’s first name as Stella.

Babitz’s sister, Mirandi Babitz, who remained Wasser’s close friend, recalled that he was “really smart and funny and very, very plugged into everything, so he was like a good addition to the scene. He was always obviously and inappropriately flirtatious with everybody but that did not particularly bother me. When he was taking pictures, he switched into this other mode and he was just completely professional.”

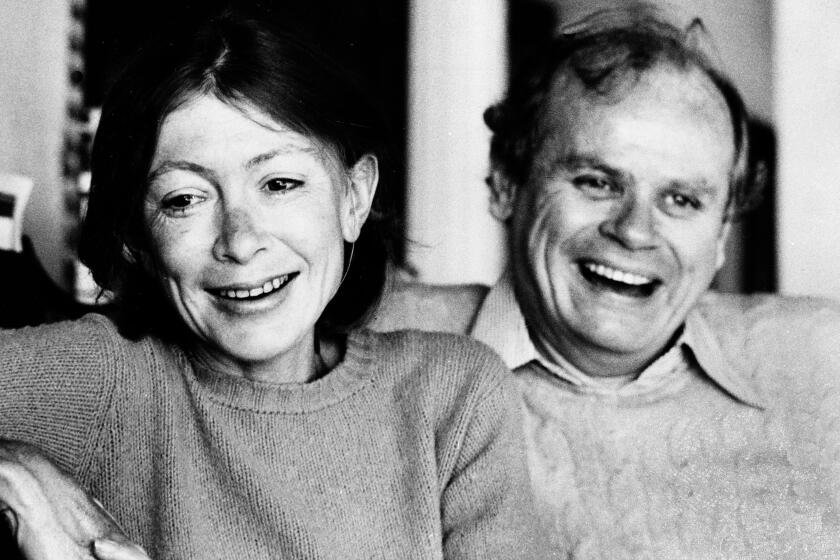

Cruising to jobs in his black Mustang convertible, Wasser had a gift for getting up close and personal with even the most remote personalities. A glance at his website, julianwasser.com, reveals seemingly informal shots of young Paul McCartney and Elton John, Hugh Hefner roller-skating with playmates and Joan Didion posing in front of her Corvette Stingray. He photographed Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel just before he was shot and was asked by Roman Polanski to document the Cielo Drive site of the Manson murders. How many opportunities can a guy get?

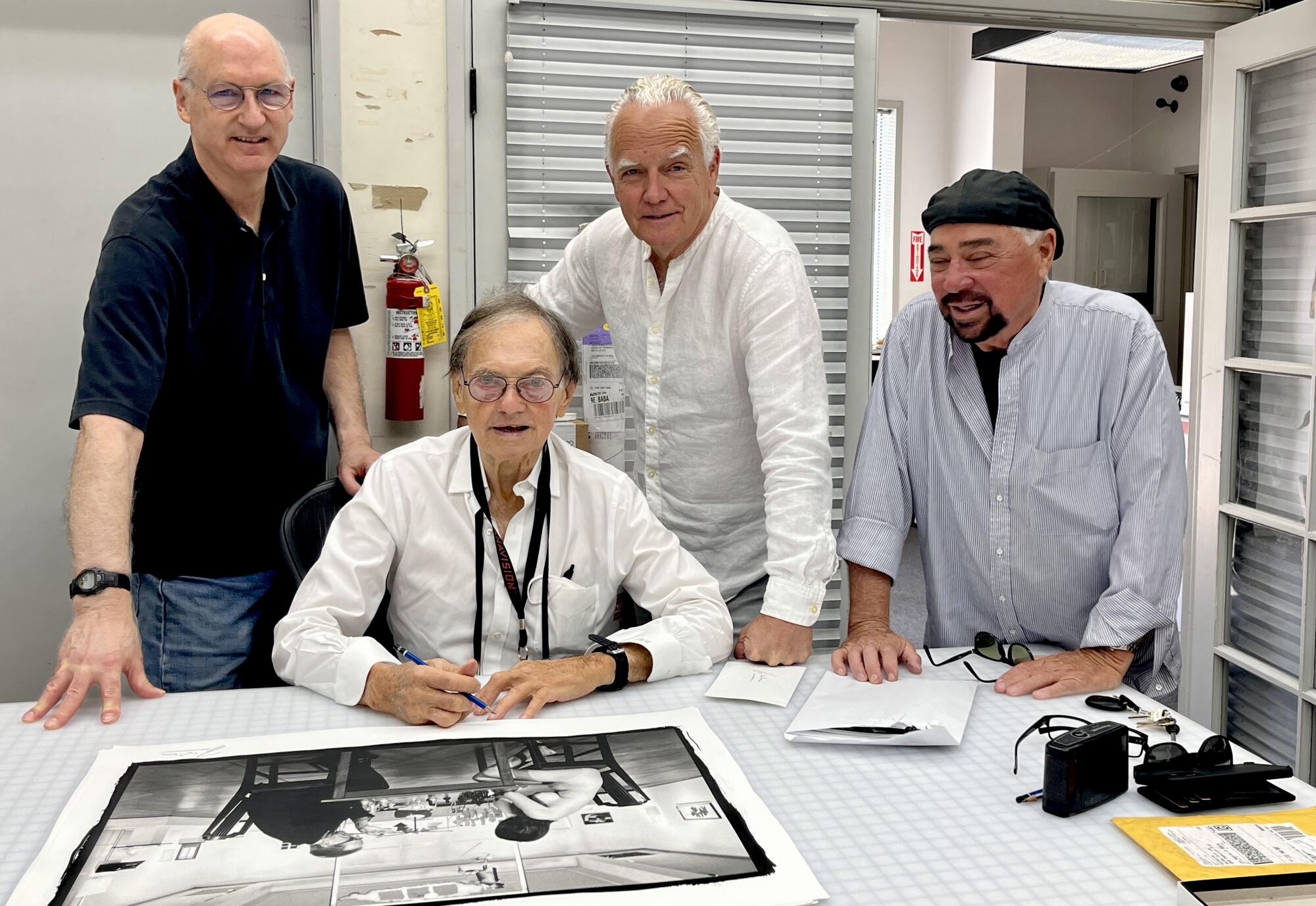

Craig Krull represents Wasser’s work at his gallery and knew him well for more than 20 years. “Everything was pretty direct and to the point in his photographs and in his conversation,” Krull said. “He was not about nuance. I think that kind of unflinching factual directness is clear in his work. He didn’t prettify anything. You get a lot of social context in his work that adds to the vitality of it as opposed to making it just an image.”

In a 2014 monograph of his work published by Damiani, “The Way We Were,” Wasser wrote, “Whether shooting the beautiful people or social documentary my intent as a photographer never changed: to be where things were happening, to meet the people who were responsible for the world we live in, and through my pictures, to evoke in viewers what I saw and felt at the instant I tripped the shutter.”

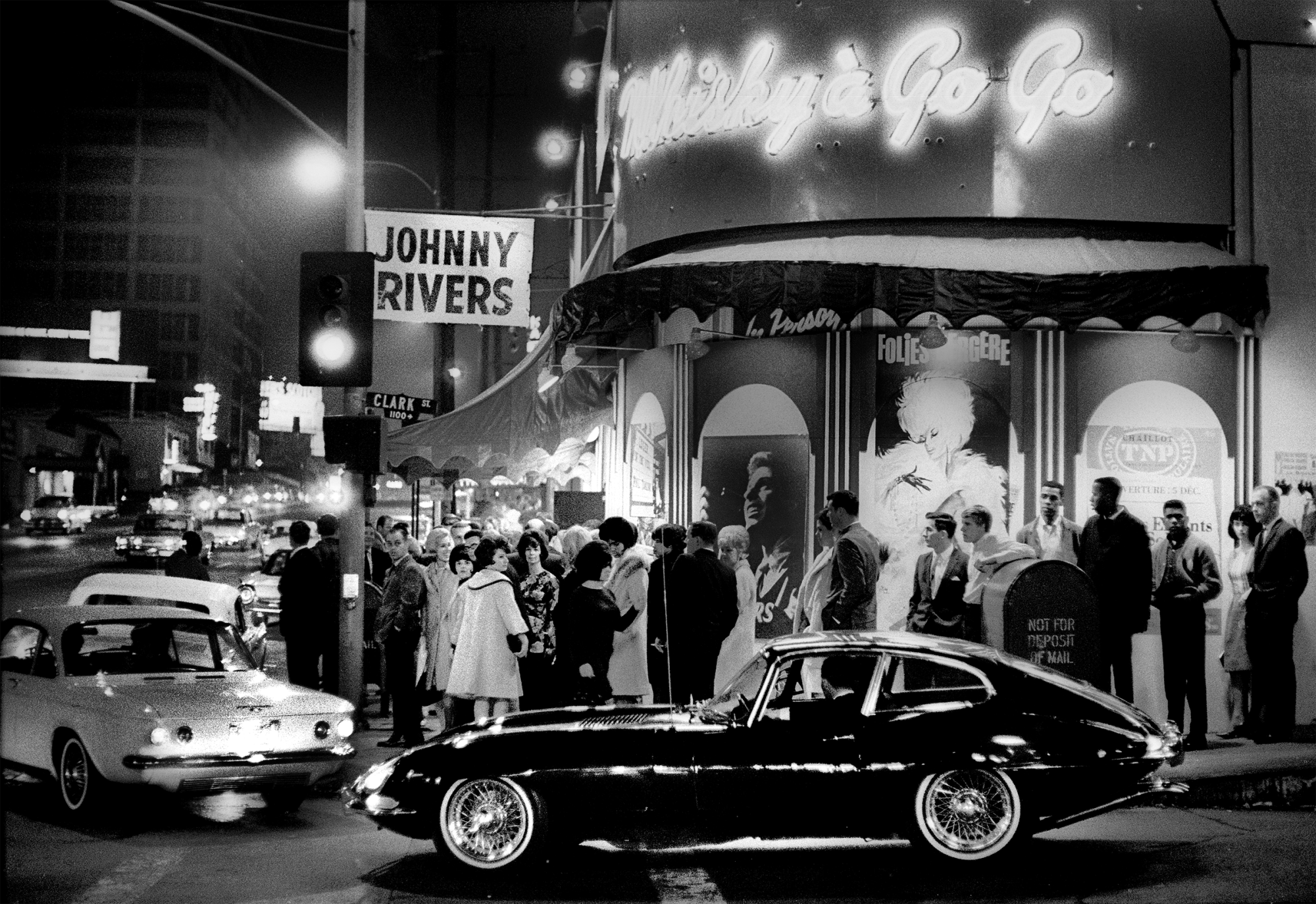

With his Nikon in tow, Wasser used his considerable gift of gab to flatter, cajole and excite his subjects. His photographs of even the most exalted celebrities demonstrate that vibrancy. He treated them like friends, once bringing Zubin Mehta, then director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, to the Whisky a Go Go. “I thought he’d get a kick out of it,” Wasser told W magazine. “He hated it: ‘Ach, my ears.’”

Born April 26, 1933, in Bryn Mawr, Penn., to Leo Wasser, an attorney, and Frances (Roth) Wasser, a schoolteacher, he was raised in the Bronx before attending the prestigious Sidwell Friends school in Washington, D.C.

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

Even as a young boy there, Wasser was shooting small news items. He later recalled, “Every night I would climb out my bedroom window and steal my father’s car when I was 12 and take pictures, and they’d be on the front page of the Washington Post. My father would say ‘look, there’s another Julian Wasser in Washington.’ I said ‘yeah dad.’”

His idol was the energetic Weegee, infamous for his unsparing photographs of crime scenes. While attending the University of Pennsylvania, Wasser decided to concentrate on photo journalism for magazines. After graduating, facing the draft, he chose to enlist in the Navy in 1956 and was assigned to a photographic reconnaissance unit in San Diego. He learned aerial photography and served time in postwar Japan. However, his frequent visits to L.A. led him to settle in the city that became his home after he left the service in 1961. “The glamor of Old Hollywood was still intact, but at the same time, everyone was approachable,” he wrote in his monograph. “There were no reserved VIP areas in clubs, no bodyguards or security men, no hordes of paparazzi.”

Wasser continued to be active in L.A. throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, working freelance for Eye on L.A. and other TV shows as well as magazines. He also settled down with Leslie Knauer, singer for the rock bands Promises and Precious Metal. In addition to his daughter, Alexi, a writer and actor in New York, he leaves behind a son, James Wasser, from a previous relationship.

Wasser was spending increasing amounts of time in Paris and Berlin when the Getty brought his images back into the public conversation via its 2011 initiative Pacific Standard Time. His pictures of L.A. counterculture, especially the photograph of Duchamp and Babitz, were widely shown and published. He was celebrated for capturing a special time in the city — and he was just as direct about his luck as he was in his work. “Everything you might have heard about living in Los Angeles in the early ‘60s,” he insisted, “was really true.”

Drohojowska-Philp is a journalist, art critic and author of “Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.