Family, friends memorialize L.A. author Eve Babitz with laughter

Standing at a podium inside a white canopy at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, novelist Emily Beyda recalled a dinner with Eve Babitz years ago that captured the late author’s wry humor.

Beyda was celebrating a book deal for her 2021 thriller “The Body Double” at the Musso & Frank Grill, and Babitz — a dear friend and longtime neighbor — was among her guests.

Sitting at a table piled high with food, most of which Babitz had ordered, Babitz said to her: “You know, Emily, your book is going to be a hit. It’s going to be a bestseller.”

“I was so touched,” remembered Beyda, speaking to a small crowd of friends and family members who gathered Sunday at the famed Hollywood cemetery to celebrate the life and idiosyncrasies of Babitz, who captured and embodied the culture of Los Angeles. Babitz died Dec. 17 from complications of Huntington’s disease. She was 78.

Eve Babitz, the author known for chronicles of L.A. drawn largely from her life, died last week at 78. See our full coverage past and present

“But immediately before I could say anything, she said, ‘And that’s why you’re going to be paying for dinner,’” continued Beyda. “And that was Eve… she was always willing to receive.”

The crowd laughed.

During the two-hour ceremony, laughter smothered tears as attendees shared tales of growing up with Babitz, of staying sober with her and falling in love with her. Collectively, their anecdotes underscored Babitz’s brilliance and kindness, her uniqueness and wry wit, and her unyielding fervor to live life by her own rules. She was someone, as Beyda said, who gave to others as much as she loved to receive.

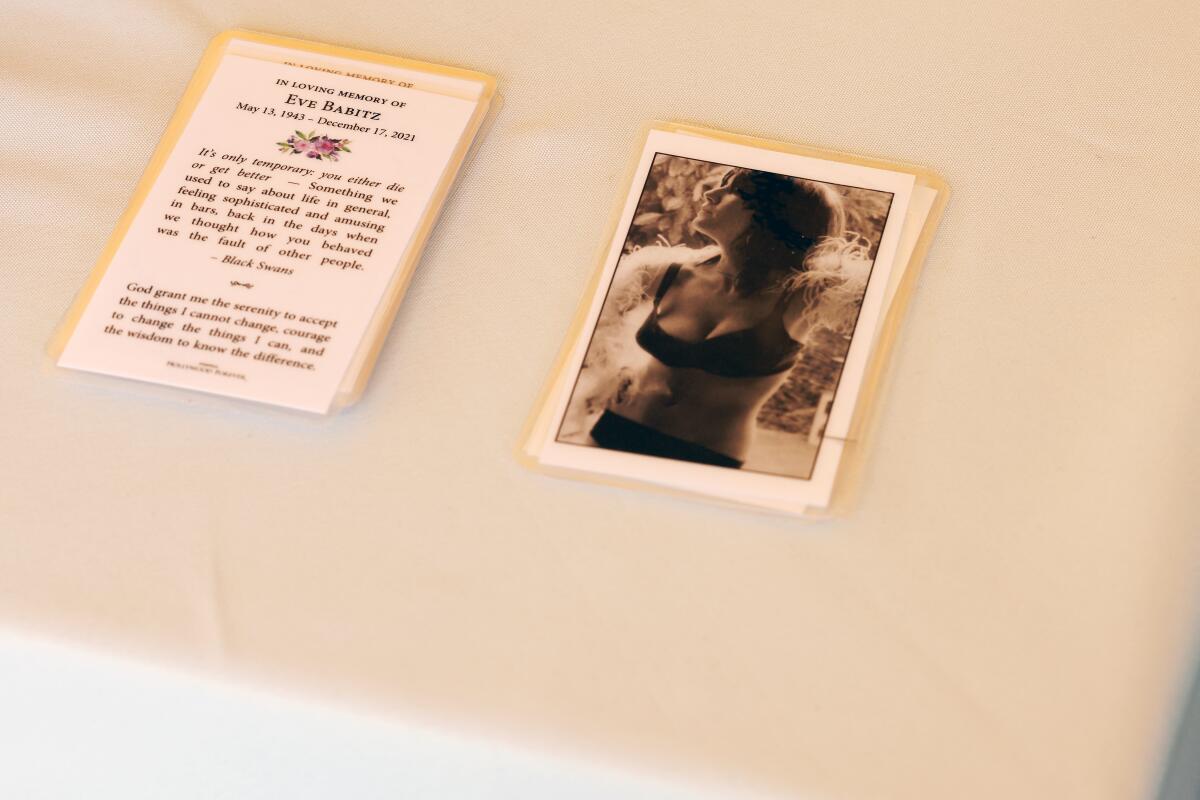

As mourners entered the canopy before the memorial, they picked up a wallet-sized, black-and-white image of Babitz in black underwear, a fuzzy scarf spread across her shoulders. A passage from Babitz’s “Black Swans” was printed on the back, and beneath it, her favorite prayer, a tenet of many recovery programs:

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Mirandi Babitz kicked off the memorial with stories of growing up in her sister’s shadow.

“I grew up in Hollywood, California, under the tyrannical reign of my big sister,” she began. “I was constantly rejected by her in the most unmistakable ways, like spraying fly-spray in my mouth, but I had a gut-aching love for her and that was that.”

She loved her even when everything she did well, Babitz found “repulsive, dull, and not up for snuff”; she still adored her when Babitz would yell from her room, “Go away, nudnik!,” borrowing a little Yiddish from their grandfather; and she found a way to forgive her after learning that when she was 8 months old, Babitz, then 3, set her on fire in her crib. “She was performing a major-key rendition of a fairy princess showing off her magnificent flaming wand and a minor-key harmonic urge to make me completely disappear at the same time.”

Babitz carried that spirit throughout her life.

“There are certain friends who come into your life and change your life forever, and I think Eve was one of those people,” said screenwriter Joshua John Miller. They met in 1992 when he was 16 years old — Babitz, he recalled, quipped that she was 17.

“I was Harold and she was Maude, and we began this journey together through the city of Los Angeles.”

They grew closer over the years, and Babitz helped him stay sober. In speeches, others also said the author helped them through recovery.

“She taught me that life can be art, that you can live a beautiful life,” continued Miller. “She had an amazing ability to take even the saddest moments, the most tragic moments, and turn them into champagne, into something bubbly. She was able to find the beauty in the sad, the hope in the pain. That’s something she gave me that I’ll always cherish.”

Artist Paul Ruscha loved Babitz’s carefree spirit, but it also made her clumsy. “She was a bull in my china shop,” said Ruscha, who dated Babitz for decades.

Whenever she would go to his place, she “usually knocked over something, broke something, tripped over something, or threw her coat on top of a plate of food without thinking of where she was putting it down.”

Reflecting on their 30 or so years together, he added, “She was a great puzzle to me. And I shall miss her long messages on my voicemail… may she be happy wherever she is now.”

Many speakers expressed gratitude to a woman who showed them what it meant to be unapologetically yourself, to live on your own terms. They said Babitz influenced how they saw the world or moved through the city — and taught them that life can be art.

Nan Blitman, Babitz’s agent and attorney, described her longtime friend as incredibly generous. But as business partners they weren’t always the best match.

“The history of my business with Eve is that somehow we would alienate all of these powerful people; that really curtailed me,” she said laughing.

Blitman recalled their first deal together: Babitz had been hired to write a screenplay for the Eagles. They sealed the deal, but without the knowledge or permission of the business manager. “He was forever angry at me and Eve, and he couldn’t stand paying her for it.”

When Babitz was told her last paycheck for that project would be late, she threatened to kill herself, Blitman recalled, “and that somehow — I don’t know how this was going to happen — she was going to put herself into the body bag with the screenplay, and the body bag would be hung out her apartment window, and the press would be called.” She got the paycheck the next day.

Though her sense of melodrama was always self-effacing, she could pierce anyone’s despair with a well-timed barb. Actor and singer Ronee Blakley became Babitz’s friend shortly after they met at Elektra Records in the early 1970s.

One night about a decade later, Blakley, who had recently left her husband, was expressing her heartache.

“You know, I liked you better before,” Babitz responded.

“Oh, Eve,” began Blakley, reciting a poem she wrote for her late, dear friend. “You were hot, you were cool, you had the biggest breasts in school… A prose poet in everyday talk, you gave it your all as you walked the walk. You lived like a man — independent and free — becoming whoever you wanted to be…”

In the 1970s, Michael Kovacevich was teaching in Dublin, Ireland, when he read Babitz’s story about the Doors frontman Jim Morrison in Rolling Stone magazine. He loved it so much he wrote to her.

In a city that gets conflated with fantasy, the late writer’s work gave permission to honor the details of everyday aesthetic experience.

After a brief correspondence, Kovacevich, who traveled from Bakersfield to attend the memorial, sent her a print of a tree he had photographed with a note saying that photography was his mental salve.

Kovacevich read Babitz’s response letter, dated April 19, 1974. “My God, you said photography kept you sane? Anyone who’d send a 5-pound photograph all the way from Dublin to someone they only knew from this one story –...?”

“Anyway,” she had continued, “it is a beautiful picture and I shall treasure it always as both a photograph and an indication of your sanity.”

Before stepping off the podium, Kovacevich said he imagined Babitz “clinking cocktails with Jim, Ray [Manzarek], Aldous [Huxley] and even Prince,” while Morrison called her out on criticizing his voice and his band name in Rolling Stone.

“Eve,” he said, his voice softening, “I’ll see you on the other side.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.