Is it possible to feel marooned in a wilderness hideaway in the middle of Los Angeles? It is if you are inhabiting the experimental home that architect Bernard Judge built for himself in the 1970s.

Set high on the crest on an impossibly steep hillside overlooking West Hollywood, the “Tree House,” as it is known, not only feels like stepping into a real-deal tree house, it seems to approximate the form of a tree with its structure.

A 1977 design story in the Los Angeles Times magazine described it as “a lark of house.”

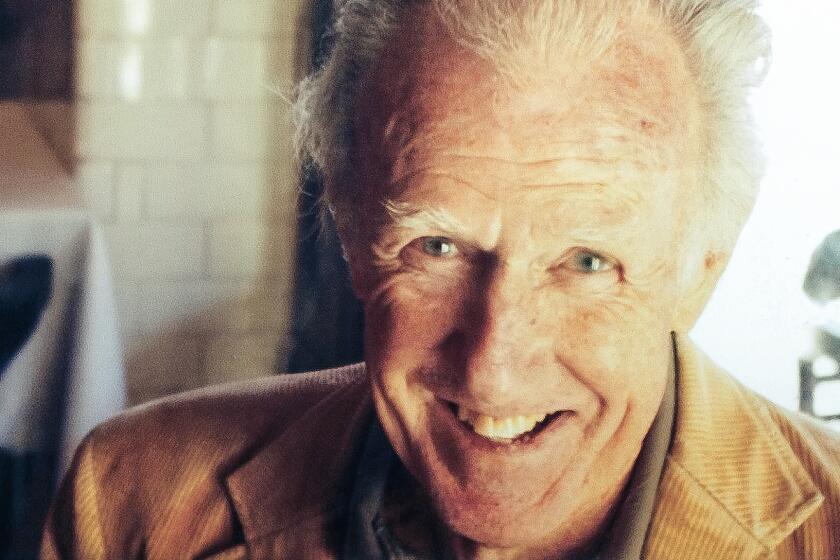

I became intrigued by the Tree House after writing the obituary for Judge, who died on Nov. 15 at the age of 90. As a designer, he came of age in the wake of L.A.’s midcentury Case Study program, devoted to exploring low-cost housing solutions. Judge was interested in those ideas, but also in issues of ecological sustainability.

Completed in 1975, Judge’s house is set on four steel columns that are planted vertically into the hillside, a structure that serves as the load-bearing apparatus for the two-story wooden structure wrapped around it. It’s as if the house has sprouted from its narrow base and is attempting to camouflage itself in the grove of eucalyptus trees that partially envelop it.

As Judge’s widow, Blaine Mallory, told me in November, “He wanted to live lightly on the land and be embedded in the environment.”

Eclectic designer Bernard Judge, who helped preserve the historic Schindler House and built South Pacific lodging for Marlon Brando, dies at 90.

On a brisk December morning, Mallory is kind enough to let me and Times photographer Christina House wander about the Tree House, a homey space studded with objects acquired across a lifetime: Andean figurines, African masks, abstract paintings. And, of course, there are the views. The house frames a vast swath of the Los Angeles Basin, and in the wake of a rainstorm, we could see all the way to the Palos Verde Peninsula. “At sunset it’s just spectacular — especially in the winter,” says Mallory. “It changes every night.”

You enter the home through its second story, which contains the living room, kitchen and dining areas, as well as a broad terrace with views of the city. A spiral staircase at the center descends to a small den and a pair of bedrooms, as well as a bathroom — the last decorated with hand-painted tiles by ceramicist Dora De Larios, Judge’s first wife, who died in 2018.

I was intrigued by the home’s compactness: a total of 1,300 square feet spread over two stories, including the terraces — space that seems intensely small in comparison with the 10,000 square-foot (and up) McMansions that clutter the hillside below.

But the Tree House’s design — the unimpeded views, combined with a high rafter on the upper level — keep the place feeling roomy. The rafter also helps ventilate the space in summer, since it contains a large louvered window that can be opened to catch breezes.

Judge also designed and built the home’s interiors — and no space is wasted. The tight galley kitchen has hyper-efficient design elements, like a spice shelf that has been carved into the wall and a narrow knife rack that occupies a sliver of space in what would otherwise be two wasted inches between the counter’s edge and a window.

Naturally, experimental homes are often rife with quirks.

The spiral staircase is big and eats up more territory than it should, though it’s worth noting that it’s a bit of judicious recycling: Judge rescued it from an earlier architectural experiment, his so-called “bubble house,” in which he made a home out of a geodesic dome (a project that landed in the pages of Life magazine).

In addition, the Tree House, on its hilltop perch, is exposed to the elements, and its glassy surfaces make it vulnerable to extreme weather — something that could likely be ameliorated by installing energy-efficient insulating glass of the sort that wasn’t readily available when Judge built the home.

Other environmental considerations, however, make the structure compelling. The house barely touches the land, resting almost entirely on its narrow steel frame pedestal — a design Judge patented — on an inexpensive lot that had once been considered “unbuildable.”

Says Mallory of the design: “It can go in a flood zone or a jungle.”

In the 1970s, Judge told The Times that living in the house was “like living in a huge toy.” But as we design with an eye toward density and climate change, this unusual Los Angeles home also offers intriguing food for thought.

The Pritzker Prize-winning designer, who died Saturday at 88, was influenced by the Case Study Houses, but critical of L.A. sprawl.

More to Read

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.