Bernard Judge, architect who turned Buckminster Fuller-style dome into Hollywood house, dies

There are few people who could say they met Buckminster Fuller, lived in Rudolph Schindler’s house, then helped preserve it, and then camped out on a private South Pacific atoll to build a rustic lodge for Marlon Brando. In fact, there may be only one: Los Angeles architect Bernard Judge.

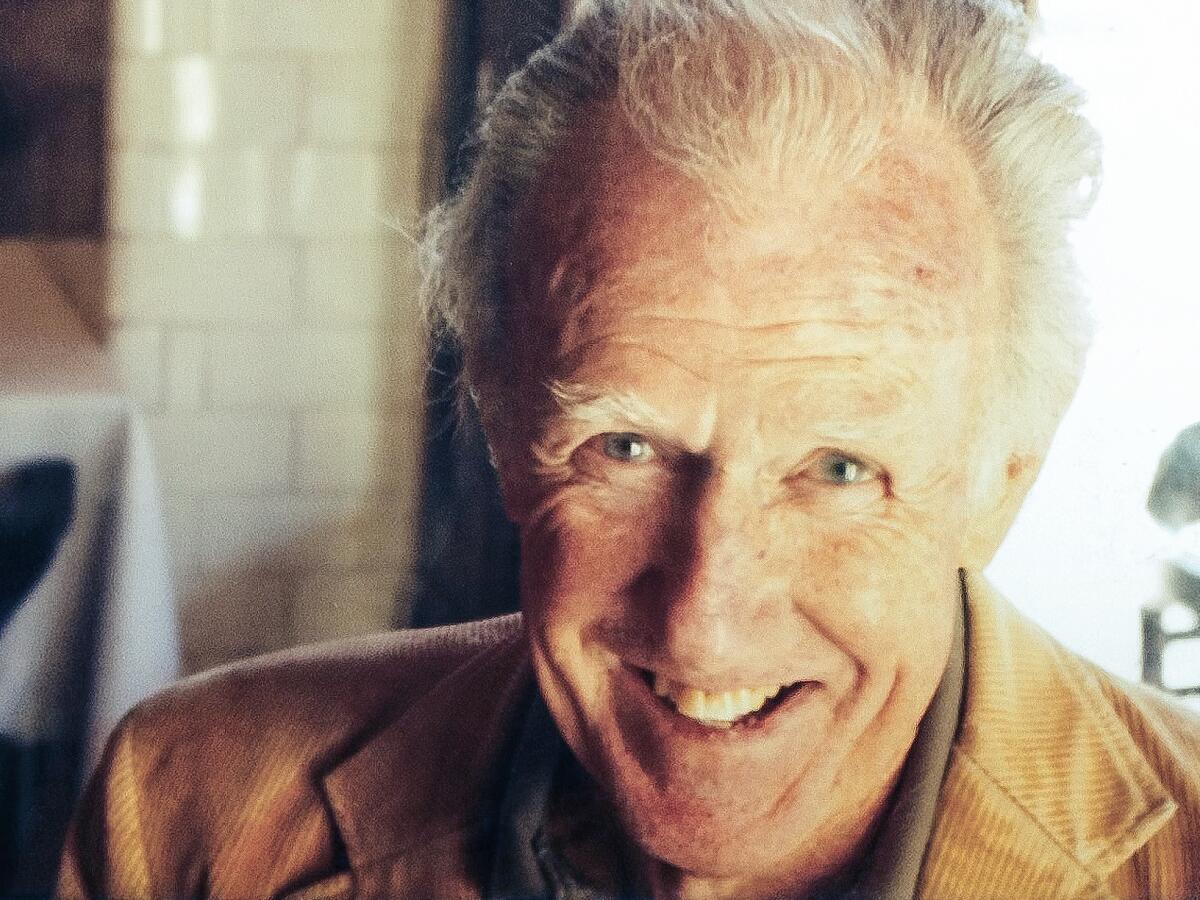

Judge, a designer intrigued by experimental and low-cost designs that reused materials and sat lightly on the land, died in his sleep on Nov. 15 at the age of 90. The architect, in fact, took his last breath in an award-winning building of his own design: a treehouse-inspired home perched on four steel columns against a steep slope in the Hollywood Hills that was described as “a lark of a house” by a Times design writer in 1977 and graced the cover of Sunset magazine in 1978. His death was confirmed by his wife, Blaine Mallory, and his daughter from an earlier marriage, Sabrina Judge.

Sabrina Judge described a curious man who had an abiding passion for design that went well beyond the confines of “capital A” architecture. “It wasn’t just about the buildings,” she said, “it was about how people lived.”

“It sounds trendy or trite to say it,” added Mallory, “because a lot of people say it now, but he had a strong connection and belief in living off the land. ... He wanted to live lightly on the land and be embedded in the environment.”

Over the course of an unorthodox career, Judge did just that.

While still an architecture student at USC in the late 1950s, he became connected to architect Jeffrey Lindsay, an acolyte of noted futurist Buckminster Fuller who, like Fuller, also designed geodesic domes and who during that era was living in Southern California. (In the ’50s, Lindsay created a domed theater for the San Diego Zoo). Lindsay supplied Judge with a dome prototype that the student then transformed into the skin of a radical-looking house in Beachwood Canyon.

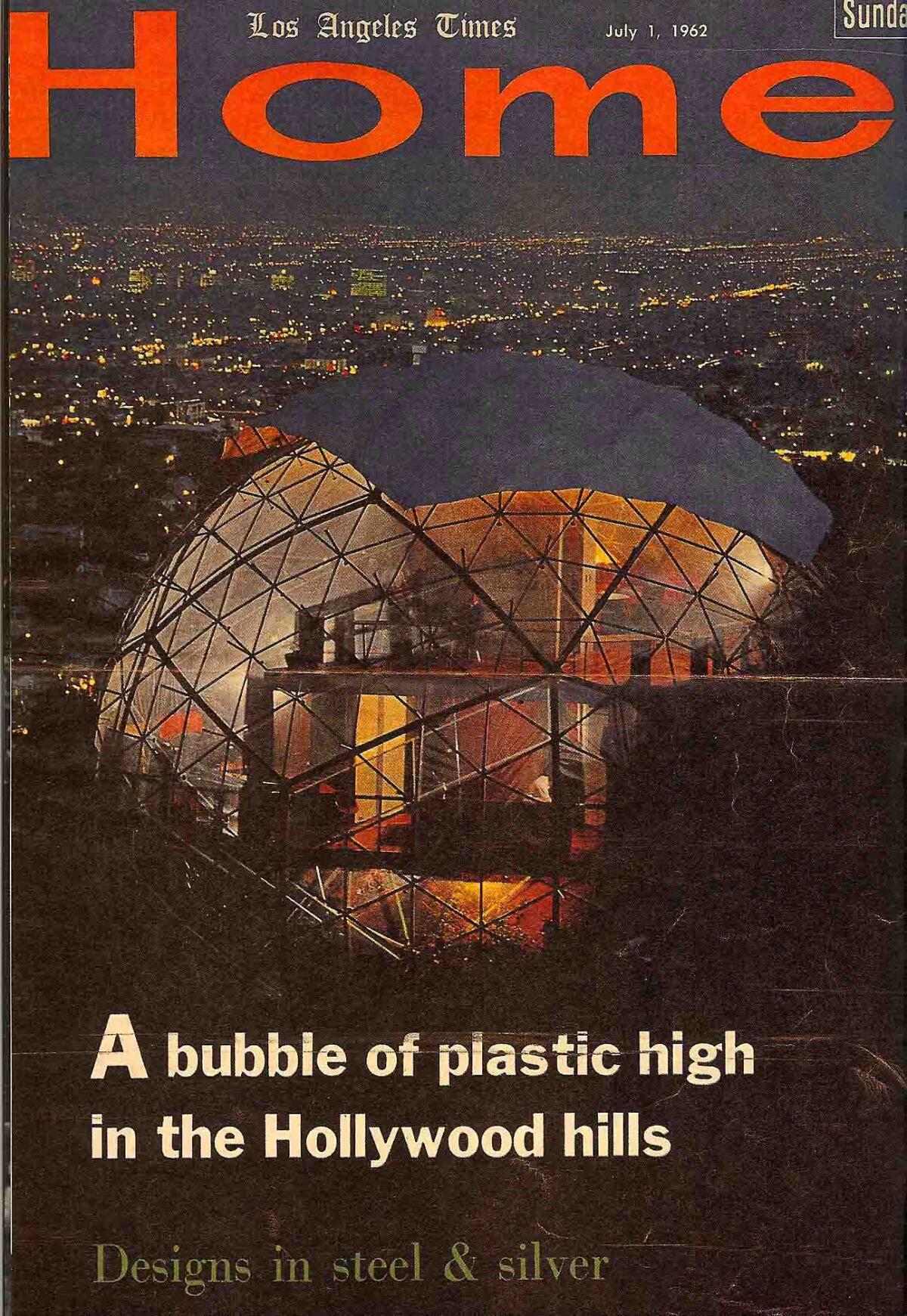

Within its spherical contours, Judge placed a two-story core that contained an open-plan layout featuring living, dining and sleeping areas. The home was such a sight — especially in the evenings, when it was illuminated — that it landed in the pages of Life magazine in 1960 as a symbol of L.A.’s forward-looking qualities before it was even complete. A 1962 newsreel described it as “looking like something to do with outer space.”

While it was formally called the Triponent House, Judge’s design became known informally as the “bubble,” especially after it was completed in 1962. That year, it appeared on the cover of The Times’ home design magazine in an otherworldly photo by Julius Shulman under the headline: “A bubble of plastic high in the Hollywood Hills.”

Judge saw the design as a way of building housing quickly, cheaply and lightly. He and various fellow USC students had constructed it and for a time, he and his first wife, ceramicist Dora De Larios, lived in it.

“Man should not have to spend most of his working life paying for the roof over his head,” Judge told Times design writer Dan MacMasters of his concept. “We have the industrial and technical potential to build low-cost houses that can be enriching and exciting experiences.”

The house, however, was impractical — offering little in the way of privacy or climate control. “It was not comfortable,” said Sabrina Judge (who is the architect’s daughter from his marriage to De Larios). “It was like a greenhouse.”

The dome was ultimately donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

In the 1920s, when West Hollywood was an expanse of bean fields stretching between oil derricks to the south and the hills to the north, the area became a haven to an eclectic group of artists, poets and architects.

In the following decade, Judge became connected to the historic Schindler House — and it happened in the most curious of ways.

In the ’70s, he placed a classified ad stating that he wanted to live in “a garden atmosphere in the middle of the city.” He received a reply from Pauline Schindler, who was inhabiting the historic Kings Road house that her ex-husband, Viennese-born Modernist Rudolph Schindler, had completed for their habitation in 1922. Today better known as the Mak Center for Art and Architecture, the house had been conceived as an experiment in communal living, designed to be shared by two couples who occupied a combination of private and shared spaces over two conjoined L-shaped structures — all of it tucked into a generous garden.

Over the years, the house had been painted and survived a fire. By the 1970s, Schindler was living there on her own. As Judge told The Times in 1980, she replied to the ad on a conditional basis: “I have what you want if I like your work.”

She did. Judge and his young family moved in.

He remained linked to the site, in one form or another, for decades. In fact, for many years, he ran his firm, Environmental Systems Group, from the house. And shortly before Schindler’s death in 1977, Judge and a team of architects and historians came together to establish the Friends of the Schindler House, the nonprofit that acquired the structure with an eye toward preservation. Judge also worked on the initial restoration project. That project led to many others around L.A.

Mallory said her husband was deeply inspired by Rudolph Schindler’s design. “He was crazy about Schindler and the whole idea of indoor-outdoor and the tilt slab walls and the use of concrete,” she said. Plus, he had “great admiration” for Pauline. “She was a bit of a bohemian,” she said. “They were simpatico in terms of their politics and their lifestyle.”

For almost six decades, Los Angeles ceramic artist Dora De Larios has been creating one-of-a-kind vessels, sculptures and monumental architectural installations embellished with fanciful flora, fauna and mythological characters.

It was during this era that Judge would end up with one of his more curious architectural commissions: designing a series of rustic bungalows on Tetiaroa, an uninhabited atoll owned by Marlon Brando in French Polynesia. Judge met the actor through a contractor, and the pair hit it off.

Brando had first laid eyes on the atoll, which lies a short prop-plane flight from Tahiti, after scouting locations for his 1962 seafaring epic, “Mutiny on the Bounty.” The actor’s hope had been to build some sort of accommodations in which to lodge friends, paying visitors, researchers and others. The development never got off the ground as planned.

Financial issues and Brando’s concerns about damaging the fragile atoll ecosystems kept the project limited in scope: Only the airstrip and a dozen rustic bungalows were ultimately built. And the conditions were — quite literally — wild. There was no place to live, no electricity, no commerce of any kind. “That was such a ‘Robinson Crusoe’ experience,” said Sabrina, who was there for spells during the construction. “We had to fish for dinner every night.”

But her father loved every minute of it — taking great care to recycle any trees felled during the creation of the airstrip as construction material for the bungalows. All of the structures were open-air, built in a Tahitian style.

“On Tetiaroa, it was about using what was there, not bringing in anything extremely foreign,” she said. “He wanted to stay within that landscape for building materials.”

In 2011, Judge published a combination memoir/coffee table tome of his experiences on Tetiaroa titled “Waltzing With Brando: Planning a Paradise in Tahiti.” A film inspired by the book, directed by Bill Fishman and starring Billy Zane as Brando, is currently in the works.

For Judge, the Tetiaroa project, like so many others, said Mallory, was about “the adventure of the design, the success of the design.”

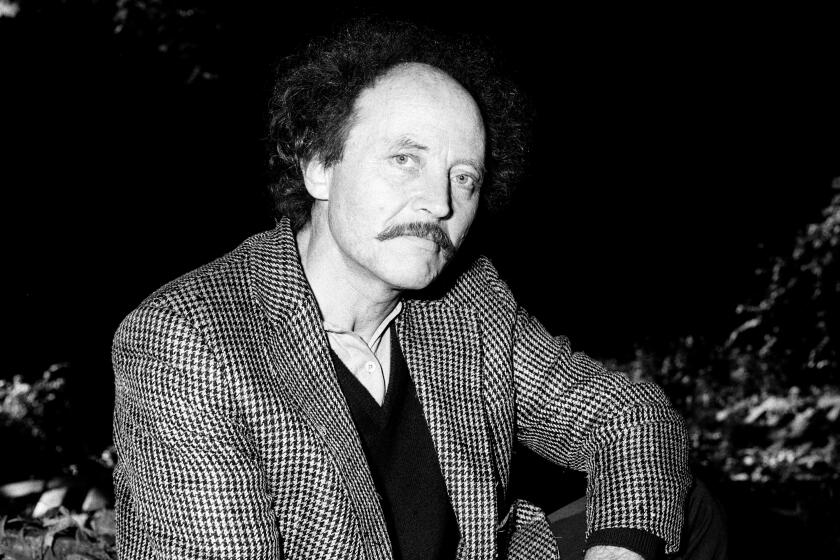

Lotringer was best known as the founder of the influential magazine Semiotext(e) — as well as for being name-checked in Chris Kraus’ ‘I Love Dick.’

You could say it was a profession that ran in his blood.

Judge was born on June 9, 1931, in Brooklyn, the son of Helene Chatelain, a painter, and Joseph Judge, an architect. His father’s work took the family all over the world, and as a boy, Judge lived in France, Nicaragua and Mexico. After high school, he served in a mobile construction battalion in the U.S. Navy and later spent a year studying architecture in Paris at École des Beaux-Arts.

Architecture ultimately brought him to Los Angeles. Judge completed his training at USC, studying under Gregory Ain and Conrad Buff III and working on the bubble house, the project that would put him on the map.

Years later, Judge described the project with fondness. In a 2011 email interview with John Crosse, author of the blog Southern California Architectural History, he recalled being “conscious of the outside weather at all times,” be it day or night. “It made for a comforting awareness.”

Unfortunately, the transparency also encouraged the curious to have come have a look. It was annoying, but it wasn’t all bad, he remembered: “I got my first client that way.”

In addition to Mallory, his wife of 21 years, and daughter Sabrina, Judge is survived by his second wife, Ulrike Zillner; a stepson, Paul Ricklen; and two grandchildren. De Larios, to whom he was married until the 1980s, died in 2018.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.