To strike or not to strike? What’s next for Hollywood’s crew workers union

This is the Sept. 21, 2021, edition of The Wide Shot, a weekly newsletter about everything happening in the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

For the record:

3:46 p.m. Sept. 23, 2021An earlier version of this post said producers are proposing increasing the number of hours to qualify for health benefits. The proposal relates to pension benefits.

So much coverage has focused on the way Hollywood’s streaming revolution has changed how the biggest names — the Scarlett Johanssons and Emma Stones of the world — are treated and paid by the big studios.

Until recently, not so much attention has been lavished on the so-called below-the-line labor, such as camera workers, set builders and hairstylists who, far from the glamour of the Emmys, work behind-the-scenes on movies and TV shows.

Tensions between the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, or IATSE, and the major studios reached a new level Monday as union leaders said they would ask their members to give them the authority to call a strike. A strike authorization vote would be an initial step toward what could be an extremely unusual work stoppage for film and TV crews.

IATSE said producers had refused to respond to its latest contract proposals. The two sides had been expected to return to the bargaining table this week. “This failure to continue negotiating can only be interpreted one way,” the IATSE negotiating committee said in a statement. “They simply will not address the core issues we have repeatedly advocated for from the beginning.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

As discussions dragged on past the four-month mark, it became clear last week that talks with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, or AMPTP, had reached a critical juncture since a deadline extension whizzed by earlier this month without resolution on their basic agreement.

The union’s international president, Matthew Loeb, issued a warning to employers over their handling of contract negotiations. An FAQ was circulated to certain locals’ members last week to prepare them for the uncertainties of the coming weeks.

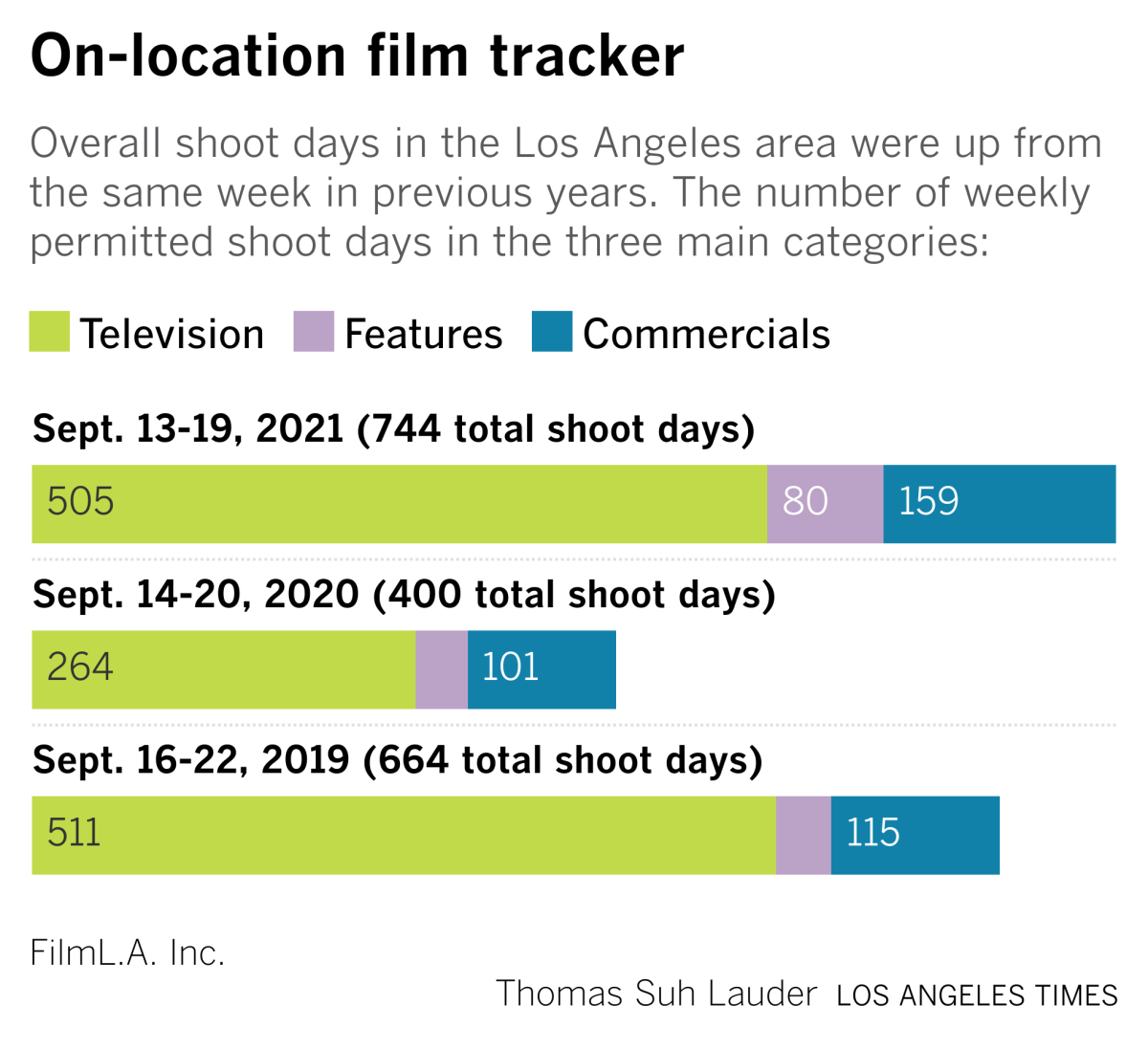

This new escalation is the Hollywood labor force’s latest attempt to flex its power as the industry evolves. Technical unions believe they have more muscle now than they have had in past negotiations. Studios and streaming services, which suffered from production shutdowns and restrictions during the pandemic, are desperate for more content, and sets can’t operate without crew.

“It’s a very interesting time right now, given the fact that we’ve had the pandemic and there’s a lot of pressure for new production to take place,” said Todd Holmes, assistant professor of entertainment media management at Cal State Northridge. “Posturing is certainly a big part of it, but they are in a better position to do something like that than they have been in the past.”

A strike authorization vote won’t necessarily lead to a walkout, but it does mean the union could call for a strike if it comes to that. Producers could also threaten to delay new productions or lock out union crew.

Loeb’s union represents 150,000 crew members in the U.S and Canada, about 60,000 of whom are covered by the motion picture and TV contracts being renegotiated. The 13 Hollywood locals’ demands reflect ongoing frustrations among the labor force at large, including long hours with little rest, discounted rates from streaming show residuals and the need for sustainable benefits packages.

Labor unions typically negotiate contracts every three years, which is hardly fast enough to keep up with the speed at which the business is shifting. Wide Shot readers may be familiar with the “Wallace & Gromit” GIF of the claymation pooch furiously laying train tracks in front of him while riding atop a speeding locomotive. That’s fairly analogous to the way labor is trying to keep pace with the changes happening in the entertainment industry.

“Except, now that’s a bullet train,” quipped one Hollywood labor source not involved in the IATSE dispute.

Here’s where things stand.

What do workers want?

Workers are demanding more time for rest, a bigger cut from the growth in streaming, an increase to wages and improved funding for their health and pension plans.

Crew members have become increasingly vocal about conditions on set, with social media accounts documenting anonymous horror stories. Work days can stretch past 14 hours, and there are countless tales of productions blowing through meal breaks despite penalties for studios. Shoots eat into weekends with so-called “Fraturdays” (overnight shoots that begin Friday and end on Saturday). Shooting days have been further lengthened by COVID-19 protocols that limit how many people can be on set at once.

The acceleration of the industry’s move to streaming is a key flashpoint. The union contends that pay rates and residuals for shows that are streamed are unfairly discounted and that crews don’t get credited pension hours on some shows.

IATSE is also asking the AMPTP for additional funding to its health and pension plans through increased employer contributions as well as new forms of funding to offset the declining residuals from traditional distribution networks. Residuals, the fees generated from reruns, help fund the union’s health and pension plans, rather than going directly to workers.

Crews complain that productions for streaming services pay less than productions for traditional media, an imbalance due to earlier contracts that deemed streaming as “new media,” which was discounted based on the idea that it’s an emerging technology. But labor argues that the “new media” designation is antiquated, with streaming now dominating mainstream entertainment, as evidenced by Sunday night’s Emmys.

What do the studios and producers say?

The producers are represented in negotiations by the AMPTP, which is composed of representatives from all the major studios including Walt Disney Co., Warner Bros., Netflix, Apple and Amazon. The studios, naturally, say the labor group’s demands are excessive. They also contend that entertainment companies have been hammered by production delays and the increased costs of filming caused by restrictions meant to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

In a Monday statement, the AMPTP said it had “listened and addressed” many of the union’s demands, including increasing minimum pay rates for some types of new media productions and covering a nearly $400 million pension and health plan deficit.

“When we began negotiations with the IATSE months ago, we discussed the economic realities and the challenges facing the entertainment industry as we work to recover from the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic,” the AMPTP said. “In choosing to leave the bargaining table to seek a strike authorization vote, the IATSE leadership walked away from a generous comprehensive package.”

People on the studio side of the aisle have suggested that much of Hollywood’s workforce is well-compensated and enjoys generous benefits, including healthcare coverage. However, crew argue that pay stats cited by producers don’t represent the experience of many people in the industry, where compensation varies wildly and some crafts pay close to California’s minimum wage.

Producers are also looking for concessions from the union, people familiar with the talks said. For example, producers want to eliminate the financial penalties they incur if crews miss meal breaks (offering to compensate them instead with an extra hour of pay, which is less than the penalty).

Producers are also proposing increasing the number of hours to qualify for pension benefits. The argument is that changes to the plan would help preserve it and that lifting the hours would ensure that crew work is the main source of income for those making claims. Currently workers can qualify with 400 hours of work.

So will there be a strike or not?

It’s unclear how serious the threat of a strike is. Some prognosticators think it’s possible but unlikely. The last time crews staged a major walkout was during World War II, when the Conference of Studio Unions, IATSE’s bitter rival, went on strike in March 1945 and some IATSE members stopped work in support.

Striking would be painful financially, especially coming so soon after a period early in the pandemic when there was little work. Some privately recall how shows were shut down during the 1980 actors strike and strikes by writers in 1988 and 2007-2008.

Still, there’s a growing sense among rank and file workers that the time has come for locals to band together and demand better treatment after years of frustrations that the pandemic exacerbated. That has probably emboldened union leadership to hold the line.

What happens next?

Each local will vote independently on whether to authorize a strike. All 13 West Coast studio locals will hold a secret-ballot vote simultaneously, electronically via email. At least 75% of those voting need to be in favor to pass the authorization. The union has warned its members that a “no” vote could impact future negotiations.

The ripple effects from previous work stoppages, such as the 2007-2008 Writers Guild of America strike, were felt for years.

Whatever happens in the current dispute, the main points of contention aren’t going anywhere soon. Writers, directors and actors, whose contracts come up for renegotiation in 2023, will surely be closely watching what happens. Pay for streaming is expected to take center stage in those discussions as well.

“I do think it sort of foreshadows what will happen in the future,” Holmes said. “When you look at the other labor unions in the industry, they’re coming up against some of the same issues.”

Stuff we wrote

— Netflix’s foreign-language shows are booming. Wendy Lee profiles Global Head of TV Bela Bajaria, the executive behind the streamer’s global push, who discusses the company’s programming strategy.

— The Emmys happened. Netflix topped all other networks with 44 wins, including top prizes for “The Crown” and “The Queen’s Gambit.” Apple’s “Ted Lasso” was also a big winner. Viewership was actually up this time compared with last year. Sure, it was up 16% from an all-time low, but still ...

— China is purging celebrities and tech billionaires. But the problem is bigger than “sissy men,” according to Alice Su, reporting from Beijing.

— The latest in our comprehensive Explaining Hollywood series: Jon Healey tells us how to get a job in sound design.

— Fed up with TikTok, Black creators are moving on. TikTokers of color say that they feel over-scrutinized and under-protected by the platform.

Number of the week

The salvation of “Manifest,” the drama canceled by NBC and revived by Netflix, has been one of the more interesting stories of the year for TV viewership number crunchers. To recap, its ratings were flagging on broadcast television, but the show proved a strong draw for binge-viewers online. Enter the fan campaign, and ta-da! Salvation.

Of course, it’s more about the numbers than the #SaveManifest tweets. Netflix recently told the Hollywood Reporter that 25 million accounts in the U.S. and Canada watched the show in the 28 days after the streamer released the first two seasons on its platform.

Is that a lot? Enough to persuade Netflix to commit to a 20-episode fourth season. It basically confirms what analysts had already gleaned from Nielsen’s weekly streaming video viewership rankings, which placed the show among its top 10 acquired programs for weeks and weeks, based on minutes viewed. More from THR: “Moreover, Manifest relentlessly stuck around in the service’s Top 10 for 71 days since its debut and was No. 1 in the U.S. for 19 days.”

It’s difficult to compare the old seasons of “Manifest” to Netflix originals such as “Shadow and Bone,” which clocked in at 55 million accounts (reminder: Netflix counts a view at two minutes watched). Netflix’s own shows are released globally, not just here in the states. What happens when Netflix unleashes its own season of “Manifest,” which will surely be promoted relentlessly on the app? This plane couldn’t hit cruising altitude on NBC. Maybe on Netflix it can.

UMG goes public

Universal Music Group, the record label home of Taylor Swift and Lady Gaga, listed its shares Tuesday on the Euronext Amsterdam exchange.

French conglomerate Vivendi, which before the listing owned 70% of the world’s largest music company, is spinning off most of its stake. UMG going public with a $39-billion valuation marks a big milestone that reflects the massive growth of streaming music. It’s a trajectory that my then-colleague Dawn Chmielewski foreshadowed in 2014 with this profile of UMG chairman Lucian Grainge.

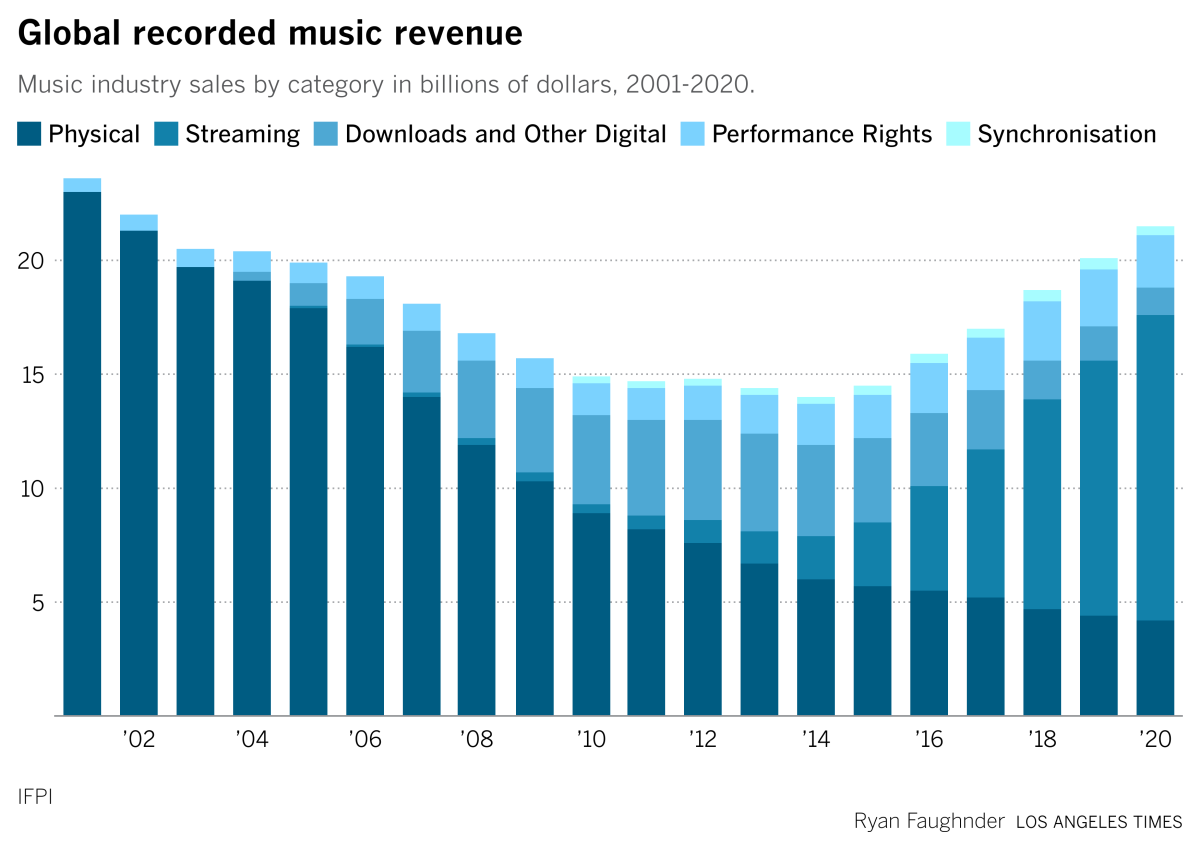

Global recorded music revenue grew 7.4% to $21.6 billion last year, according to the IFPI’s annual report. A full 62% of that revenue came from streaming services such as Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube Music and Pandora. Popular apps including TikTok and Snap, as well as fitness company Peloton, are also proving the value of licensed music, even for consumers who came of age in, or were born after, the Napster era.

You should be reading...

— The unwritten rules of Black television. Most of Hollywood’s writers rooms look nothing like America. Could that be changing? (The Atlantic)

— Everyone’s talking about the Wall Street Journal’s blockbuster investigative series about Facebook.

— Lachlan Murdoch becomes a serial dealmaker at the head of the Fox media empire. The company recently bought assets including Outkick and TMZ. (FT)

— AMC says it will accept cryptocurrencies beyond Bitcoin. I remember when reserving tickets online was considered a newfangled innovation ... (Reuters)

Final shot ...

I haven’t yet started watching Amazon’s “LuLaRich,” the documentary about the rise and fall of multi-level marketing firm LuLaRoe, known for its printed leggings (apologies to my friends at the Screen Gab newsletter). I’m in the midst of a “Sopranos” binge, which I realize is a somewhat embarrassingly early COVID thing to be doing this late in the pandemic. Nonetheless, it’s good to see the capitalist-cult documentary continuum is alive and well!

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.