Fall Preview Books

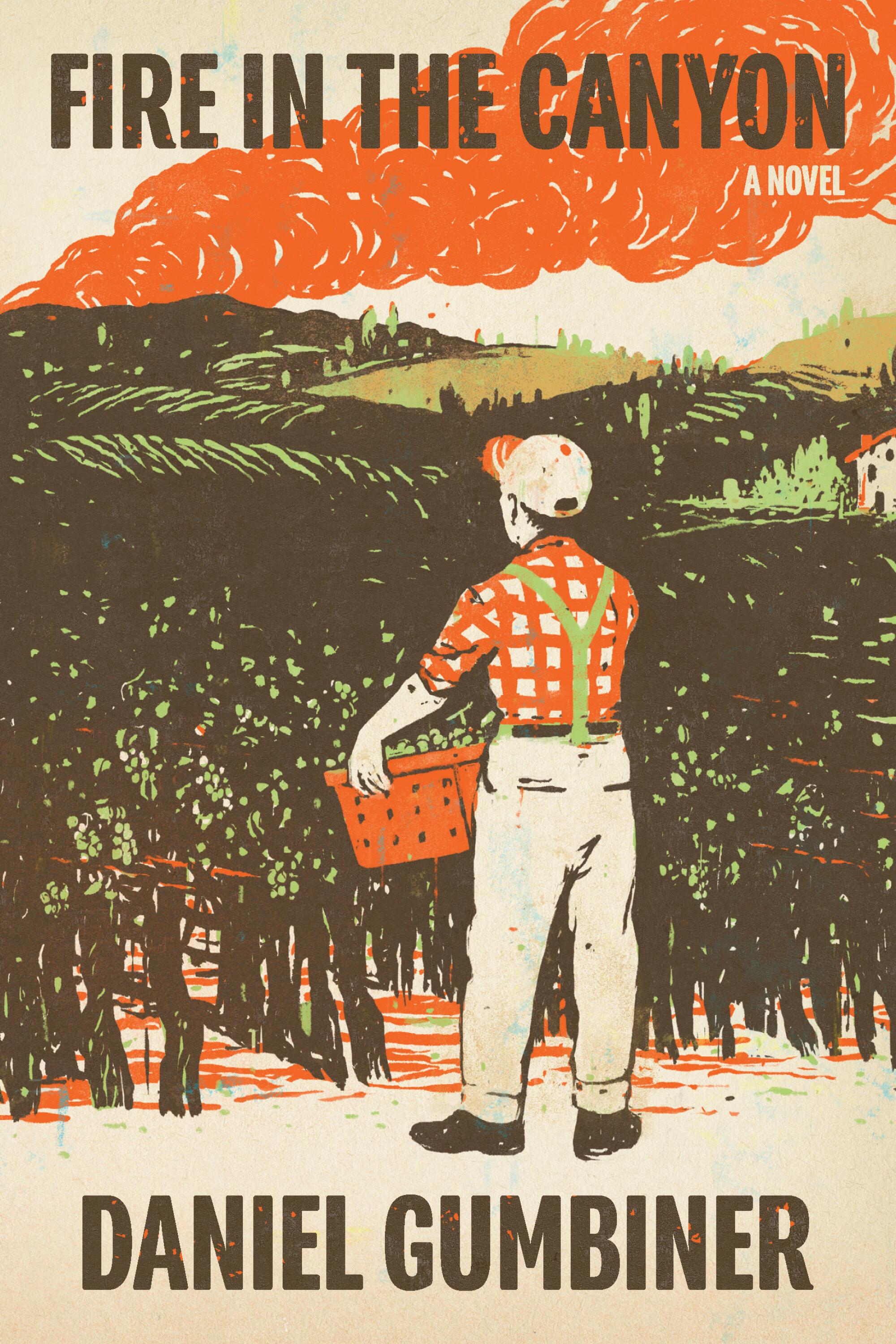

Fire in the Canyon

By Daniel Gumbiner

Astra House: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The novel “Fire in the Canyon” opens with a view: Pot grower turned winemaker Ben Hecht surveys the few acres of land he owns in the Sierra foothills — a grape orchard, a few sheep. This is where it started for the author too.

“I wrote that first scene of him moving through the farm and populating it with everything that was there,” author Daniel Gumbiner explains in a Zoom interview from his home in Oakland. The foothills, where he spent a good deal of time growing up, were “a kind of mythic place from my childhood.”

“Fire in the Canyon,” out in October, certainly has mythic overtones. It is a kind of Steinbeck saga with more modern catastrophes in mind; instead of the depredations of the Dust Bowl and the Depression, the Hechts face the twin crises of economic precarity and climate change. But just like Gumbiner’s debut, “The Boatbuilder,” which was longlisted for the 2018 National Book Award, his follow-up is a novel of people more than ideas.

Gurba’s essays, collected in ‘Creep,’ showcase an unblinking gaze at gender-based violence and other cruelties, which the author would rather be known for.

“I kind of follow my nose and pay attention — it’s learning to move through the world as a writer,” says Gumbiner, who also edits writers as head of the Believer magazine.

Early on in the novel, fire breaks out and destroys part of the family farm. Gumbiner says he was more interested in exploring the aftermath than the disaster itself. “The fires are very extensively covered in the moment when they’re occurring by national media, as they should be,” he says. “Then the media departed, and there’s all these other stories that are transpiring, the day-to-day minor dramas. That tends to be what I’m more drawn to in my fiction.”

Gumbiner says he begins by “finding the thing that drives my curiosity” and then navigating through the narrative fog in search of connections. A Sunday boatbuilding class and conversations with its teacher inspired him to write “The Boatbuilder,” in which a tech industry refugee addicted to opiates finds a way back to life through studying with a reclusive master of the craft. His second novel grew, in part, out of an interest in winemaking. He struck up conversations with various vintners — and kept coming back to one friend who had survived a large wildfire.

“He said one of the first things that happened was that he was put into a relationship with all these people around him,” says Gumbiner. “And some of these became lasting relationships. The seeds of the book in my mind became the way that fire could change the trajectory of a community or an individual’s life.”

The Hechts are not exactly on solid ground to begin with. Ben and his son, Yoel, are estranged after the father’s cannabis business ended in jail time. His wife, Ada, is a novelist whose books have paid down the mortgage. The fire destroys her latest manuscript and threatens to burn up Ben’s second chance at a vocation. But it also gives him a second chance with Yoel, who returns to help rebuild. There is much to be repaired — family, livelihood, land. The fire is the catalyst, the farm their crucible.

Lydia Millet, whose latest novel, “A Children’s Bible,” tackled climate change, reads new fiction on climate and argues against calling it a genre.

“All the characters are flawed,” says Gumbiner, “but through those flaws and under the right conditions, people can do great things. It’s a comfort to me that there is a place for everyone, and everyone, even in their weaknesses, can be of use.”

Repairing what has been broken is not just a theme in Gumbiner’s novels: It’s also his job as editor at the Believer. Founded in 2003 as an alternative to the snarkier East Coast literary journals, the beloved Bay Area magazine was published by Dave Eggers’ McSweeney’s before being sold in 2017 to the University of Nevada Las Vegas (around the time Gumbiner came on as managing editor). Last year, as its literary program foundered in the wake of a Believer editor‘s resignation, UNLV folded the magazine and sold its archive to a website that specialized in sex toys. After much uproar, it was resold — back to McSweeney’s — with Gumbiner at the helm.

“It was wonderful to see how much it meant to people,” the author says, noting the Kickstarter effort that funded the repurchase. “It was really moving, sort of like watching your own funeral and seeing what people say — but then getting revived.”

The “stress and sadness” of the magazine’s recent years is something he doesn’t want to minimize in touting “Version 3.0.” But the community effort to revive it, and the ongoing struggle to redefine it, feels like regeneration after a fire. “I think one of the things I’ve learned is that you have to let it change,” says Gumbiner. “You want to retain some of the structure, its tone and feel, but you also have to let it take its new shape.”

After being sold by UNLV to a digital marketing company, the Believer magazine has returned to its original longtime publisher, McSweeney’s.

With the help of contributors new and old, Gumbiner is rebuilding a magazine community. Not unlike his characters in “Fire in the Canyon,” who are learning to cope with climate change, his staff is adjusting to a depleted landscape. He could be speaking of both when he says, “All of us are dealing with this cloud that’s hovering over all of us … and that has affected the story of the way we see the world and understand our lives and our place in it.” Gumbiner is repairing his patch of the world, and he isn’t alone. It’s a long road ahead.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.