How ‘Feud’ explores a parade of great pain — Capote’s and the Swans’

Jon Robin Baitz hit the big time as a playwright at a young age, earning acclaim and awards attention for such works as “The Film Society,” “The Substance of Fire” and “The End of the Day.” He went on to pen a string of other successful plays while also expanding into writing for film and television, most notably creating the long-running ABC series “Brothers & Sisters.”

More recently, he paired up with Ryan Murphy for “Feud: Capote vs. the Swans,” the second installment in the uber-producer’s FX anthology series, following 2017’s “Feud: Bette and Joan.”

Baitz, showrunner and sole writer on the new “Feud,” loosely based its eight episodes, which involve famed “In Cold Blood” author Truman Capote’s later years and fraught friendship with a circle of New York high-society women (his “swans”), on Laurence Leamer’s 2021 book “Capote’s Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era.”

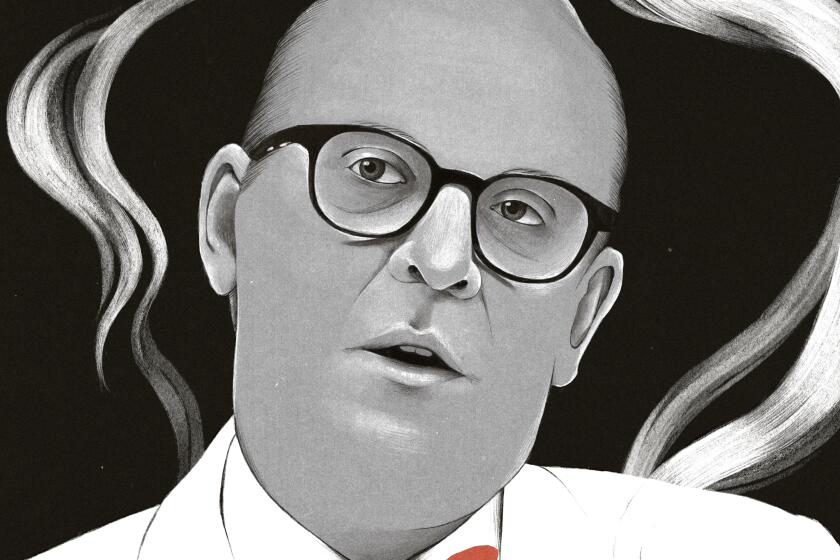

Forty years after his death, Truman Capote continues to draw audiences in for another lascivious story and another dramatic portrayal in ‘Feud: Capote vs. the Swans.’

The series is marked by its sharp writing, directing and period re-creation, as well as by Tom Hollander’s indelible turn as the troubled Capote and the starry list of actresses (including Naomi Watts, Diane Lane and Chloë Sevigny) who vividly inhabit the “swans.”

Baitz, 61, phoned in from his Manhattan home (he splits his time between New York and California) for a leisurely and reflective chat with The Envelope about his latest project.

How did you choose to structure and tell this period of Capote’s life story? How much did you rely on your source material?

We were most interested in this particular time and theme, which is the last part of his life when the chickens came home to roost essentially and he was left in a kind of desperate situation muddled by pharmaceuticals and alcohol, terribly lonely and losing friends. There’s not an incredible amount of literal transposition of material from [Leamer’s] book to the screen. A lot of it is this meditation on friendship that lives between the lines of the book.

The book is very good with a broad spectrum of facts. What’s underneath the facts is a kind of parade of great pain, and I think what Ryan and I were interested in mostly were the consequences [of that]. We really felt this material was a way to explore aging and friendship and loss and the love of friends, yet also, at the same time, my continuing interest in what it means to be a writer who takes life and uses it.

Capote was a notoriously difficult and polarizing but also fascinating figure. How did you approach his portrayal?

With a kind of deep sorrow for him. Some of the people who knew him have commented that it’s a very unsympathetic portrait, but he had become a very unsympathetic man in many respects. Mike Nichols, who I was friends with, said to me that Truman Capote was the only man he’d ever met in his entire life who told lies simply to hurt people. I did think about that descriptor and how you get to be that and the pain it takes to get to be Truman. I thought it was multiplied several times by Tom Hollander’s infinite humanist capacity for empathy.

What a phenomenal performance.

It really is. It was a blessing even though there [have been] other sort of wonderful iterations of Truman. I do believe that Tom’s, even though it’s the least sympathetic in many respects, is the warmest, paradoxically.

Did you discover any surprises about Capote along the way?

I think rather than that happening, I had a deeper sense of what you lose when you become desperate — and whether that desperation includes the self-annihilation of booze and pills, and trying to hold onto a kind of fame that doesn’t particularly exist in the world of the 1970s and ’80s and onwards anymore.

I saw it all as an avalanche of cautionary tales, in the negative space: Hold onto your friends dearly, cherish your friends, respect them and honor them, and try to be the guardian of your own talent — because if you’re blessed with some, the clock is always ticking.

Making it felt like working on a very long and kind of heartbreaking novel.

The Black and White Ball episode was conceptualized as unseen footage shot by Albert and David Maysles, the celebrated nonfiction filmmakers.

I loved the episode in which Capote spends the day with James Baldwin. But that never actually happened, did it?

No, I take great pains to sort of try and telegraph that because there was a lot of ambivalence or jealousy even from Truman toward Baldwin. A kind of strange energy from one gay man [and writer] to another. I think Baldwin was more generous and more involved in his nature but Truman was cruel about Baldwin on paper, which is simply another example of Truman’s uncalled-for lack of generosity.

What do you think you brought to writing this story now that you may not have during your “wunderkind” years?

I think maybe my youthful willingness to be judgmental about characters has been tempered. My instinct about the answer to that, I guess, lies in the depiction of Truman and [friend and ex-lover] Jack and how much love he has for Truman and how forgiving he is. I suppose I come down more adamantly now on the side of humanism rather than special dispensation for the talented. I don’t think genius gets a pass from being kind, and I try to live that way. I find brutal behavior now less exhilarating and more troubling to write about. I think my voice is maybe a little sadder, older, kinder.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.