Review: His father’s legacy was addiction and neglect. How Obed Silva lived to tell the tale

On the Shelf

The Death of My Father the Pope: A Memoir

By Obed Silva

MCD: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“I take it death can’t be so bad, on account that we all must die,” Obed Silva observes in “The Death of My Father the Pope.” “So why is it that we make such a fuss over life?” The question lingers beneath the surface of this memoir like a stain. Silva himself has come back from the brink more than once: A former gang member (a gunshot at 17 left him paralyzed from the waist down), he is now a professor at East Los Angeles College. “Seven times,” he writes, “I’ve almost died, and I’ll probably have a few more encounters with death by the time I finish telling this story. … But here I am still, for now.”

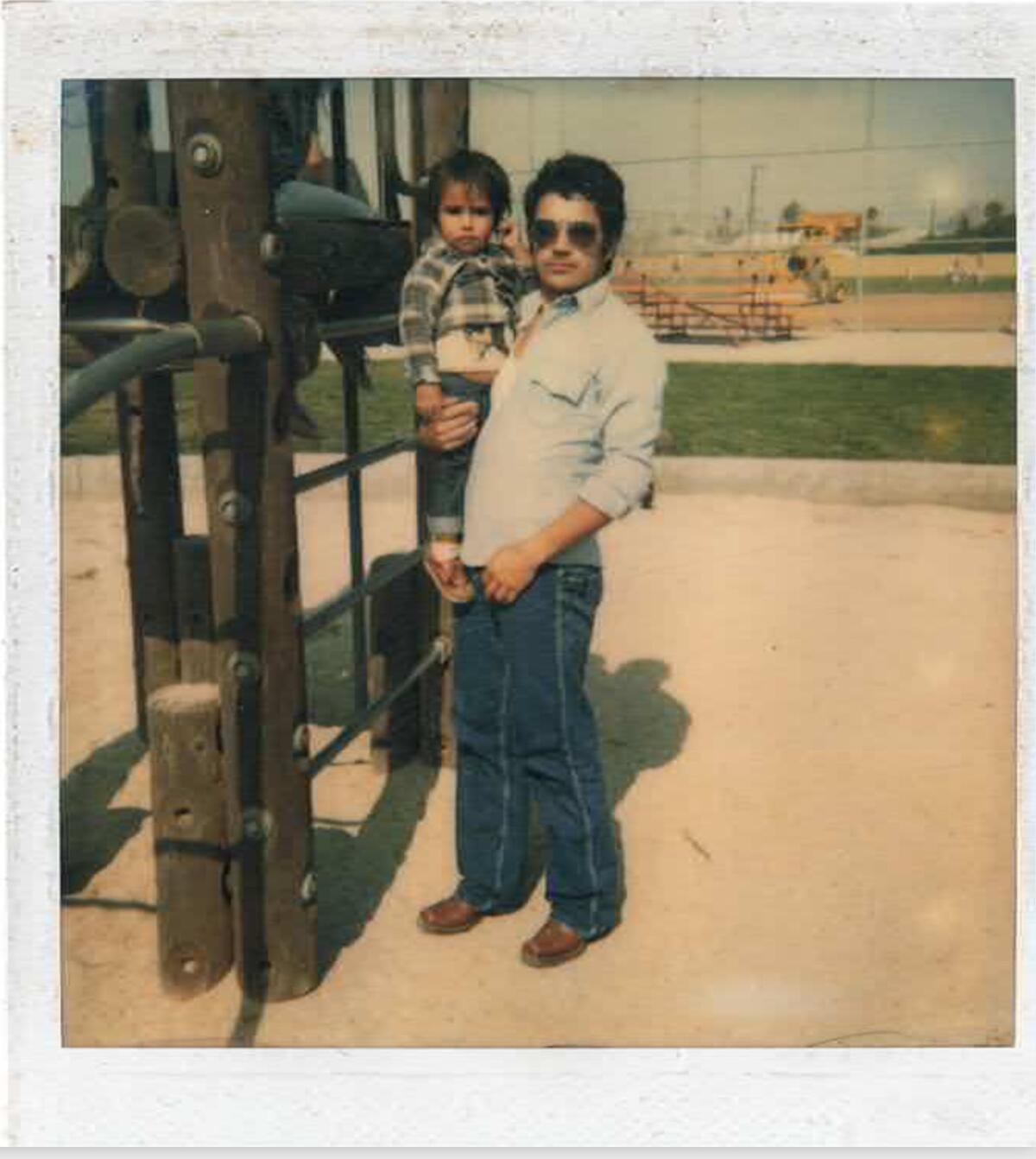

A sense of tenuousness — or, more specifically, of the fluid interplay between death and life — is a key factor in “The Death of My Father the Pope,” which opens with the death of the author’s father, Juan, an artist and alcoholic who drank himself to death in Chihuahua, Mexico, in 2009, at 48. Silva structures the book, his first, around his trip across the border for the wake and burial, but this is no linear reckoning. Instead, the memoir weaves back and forth in time, using memory and language to shade or expose the complexities of the father-son relationship.

Take the word “pope,” which for Silva carries multiple meanings. On the one hand, “In Spanish pope translates to papa, which is the same word used for dad.” On the other, his father was nothing if not larger than life: the Pope to a quasi-literal degree. “It’s all his doing, his work, his magnum opus,” Silva imagines saying to his younger sister. “Your father was the pope, didn’t you know, and everything he did was holy. This is why they cry for him, this is why they mourn his death.”

Silva’s observation is both direct and hyperbolic, which might also be said about “The Death of My Father the Pope” as a whole. The author loved his father but hated him as well, and his response to the death is elation and relief. He only goes to Mexico because of his mother’s insistence. “You need to heal,” she counsels, “and you can’t do that unless you forgive your father. It’s the only way you’re ever going to close those wounds.”

Judge holds the fate of a gang member-turned-Cal State L.A. scholar

Their exchange establishes the essential tensions of the memoir — between the past and present, the sins of the father and the sins of the son. “This woman,” Silva reflects, “who’d raised me all on her own without asking for anything from my father — not a cent — was showing me what real strength looked like. It wasn’t in muscles or in violence or in superiority; it was in meekness and humility, in simply saying I forgive you and moving on.”

For Silva, however, it’s not that simple. “Father, why can’t I cry for you?” he wonders. “Is it that you haven’t left me yet? Is it that I still carry you with me everywhere I go?” Silva makes such contradictions explicit when he views the body — “Remember the monster,” he reminds himself. “Remember the fury” — and cuts his thumb removing a protective sheet of plexiglass. “A drop of blood from my finger falls onto my father’s face,” he recalls, “and lands on his cheek just below his right eye.” Remembering the tattoo of his name on the dead man’s chest, Silva works open his father’s shirt and writes those letters again below the faded ink, this time etching them in blood. “You were my father, and I am of your blood,” he whispers. “I am your son. I am your son. Take it, Daddy, take your blood with you.”

What Silva is exploring is patrimony, which in his case is a minefield of loss. His memories, which keep rising to infuse the present, are fraught: if not always brutal then often charged. Every positive recollection — a trip to Ensenada with his father and half-brother Danny; a visit to Los Balnearios Robinson, a Chihuahua water park — comes tempered with its inverse: the night Silva’s father tried to enlist four friends to help beat his children, the evening that ended in a brothel after he took Silva to score drugs. “This is where I first buried my father,” the author notes. “I buried him here, where I found solace in a conversation with a prostitute. Here is where the funeral took place; here is where I laid him to rest.”

Out this week, ‘The Deeper the Roots’ is an intimate, personal story of defying odds, helping others do the same and making history along the way.

This eulogy of sorts offers little room for grief. “My father loved us,” Silva concedes, “but he loved us in the way that only a sick man can love anybody: indelicately. … He would kiss us one minute, and ridicule us the next. He would hand us a dream with one hand and crush it with the other.”

Eventually, enough became enough — for Silva and also for his mother, who moved with him to California when he was a young boy after suffering escalating waves of violence and abuse. “Since he has caused her much emotional anguish and physical pain throughout her early adult life,” he writes in the acknowledgements, “my mother would like little to do with anything involving my father. By the end of this book, you will fully comprehend why.” The final chapter of the memoir, which details Silva’s conception, presents a creation myth that is the opposite of immaculate, a manifestation not of redemption but of his father’s primal sin.

The power of “The Death of My Father the Pope” lies in Silva’s willingness to address even this; he never looks away. His book is an unrequited love story, told in fragments, through the lens of death. “I wish that I could hug him,” Silva thinks as his father is being buried. “I wish I could feel the stubble on his cheeks.” Instead, he is left with something more elusive but also sharper: vindication.

“How ’bout it, son, we die together,” Silva imagines his father asking, while in his head, he provides the only answer: “You first, Dad, you first.”

In “One Friday in April,” Donald Antrim reframes suicide as a state rather than an act — and marks its toll as vividly as anyone since William Styron.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.