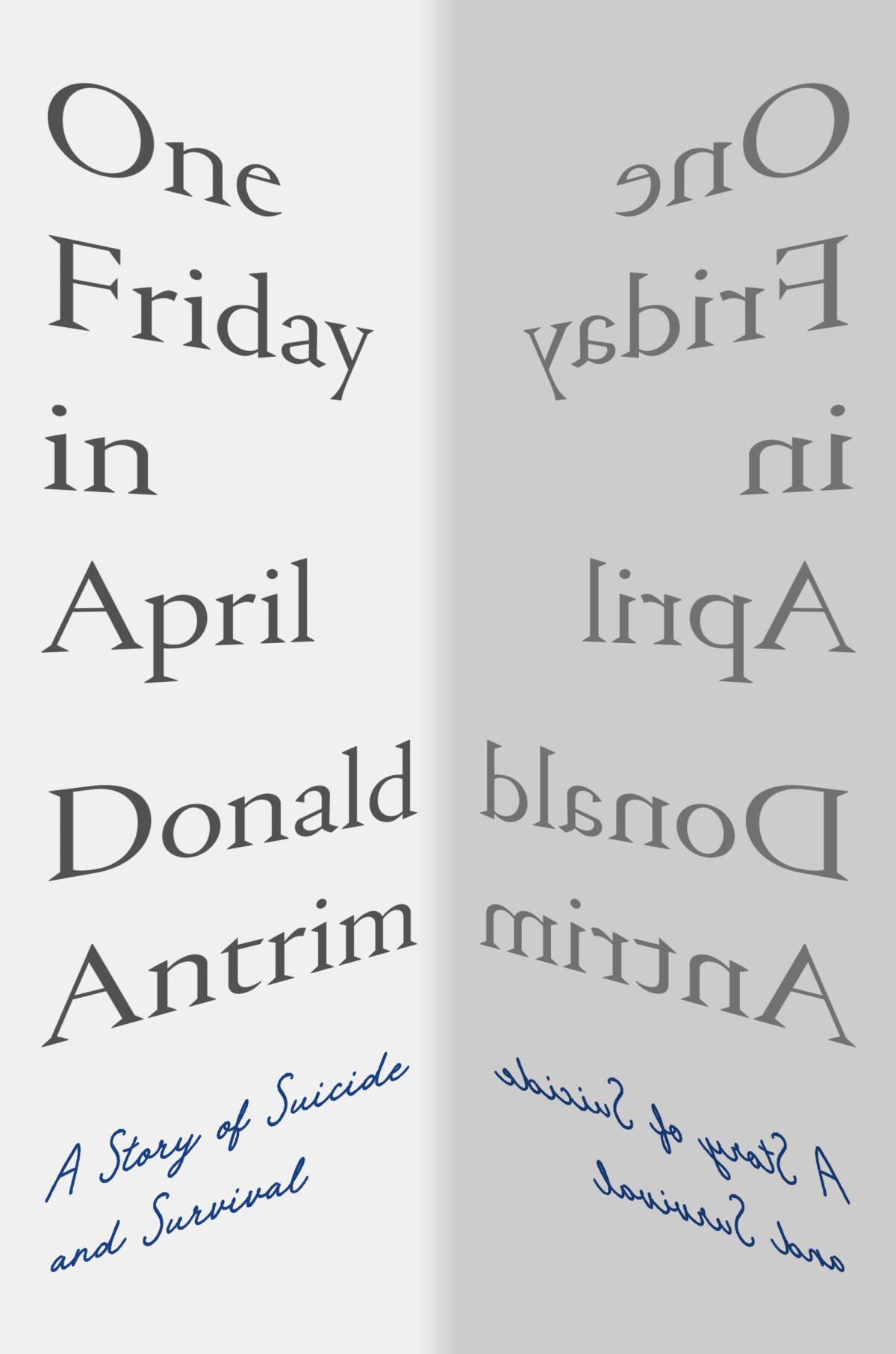

Review: Donald Antrim struggled with suicide for years. In a brilliant memoir, he redefines it

On the Shelf

One Friday in April: A Story of Suicide and Survival

By Donald Antrim

W.W. Norton: 144 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

At the end of “One Friday in April,” Donald Antrim frames a domestic scene: his wife, Marija, plays the piano while he sits “on the living room sofa, writing to you.” It’s a small moment, intimate yet generous in the way it seeks to include us. It also seems to represent a point of closure — or as near as Antrim’s brief and devastating memoir gets to one.

The author is in the same home where he lived in 2006 when, suicidal, he spent a Friday “afternoon and evening pacing the roof of my apartment building in Brooklyn, climbing down the fire-escape ladder and hanging by my hands from the railing, then climbing back up with sore palms and lying on the roof, in a ball.” Years later, every night, he and Marija see that fire escape “outside the bedroom window, its dark outline against the city sky, the metal steps going up or down.”

We might wish to read this as recovery or reconciliation, but Antrim has other ideas. “What will you remember?” he implores in the book’s closing sentences. “What will you write in a letter to a friend you can trust?” It’s a full circle moment that resists closing the circle, not least because it ends with question marks. Resolution is not what Antrim has in mind.

“One Friday in April” evokes, as vividly as any book since William Styron’s “Darkness Visible,” the ongoing present tenseness — or present tension — of suicide, which Antrim describes as a condition in and of itself. “When telling the story of my illness,” he observes, “I try not to speak about depression. … A depression is a concavity, a sloping downward and a return. Suicide, in my experience, is not that. I believe that suicide is a natural history, a disease process, not an act or a choice, a decision or a wish.”

He’s interviewed Neko Case, Jeff Tweedy and Maria Bamford about depression. With his new memoir, “The Hilarious World of Depression,” John Moe looks inward.

Antrim has excavated similar territory throughout his career; his 2006 memoir “The Afterlife” — whose publication was a precipitating factor in his breakdown — examines his fraught relationship with his mother, while many of the stories in his collection “The Emerald Light in the Air” (2014) portray characters who are disrupted or unbalanced, doing their best to remain alive.

With “One Friday in April,” however, he has embarked on an essential reimagining: suicide not as act or outcome but as illness, chronic and debilitating, even when it doesn’t end in death. “My sickness lasted years,” Antrim goes on. “It continued after that Friday on the roof, and went on for more than a decade, through long hospitalizations and more than fifty rounds of electroconvulsive therapy, once known as shock therapy. It lasted through a decade of recovery, relapse, and recovery.”

In revealing so much at the beginning of the memoir, Antrim telegraphs his intentions, which are to explore the experience of his illness rather than its arc. We know he has survived, of course, but the terms of this survival remain conditional, even so many years after the fact. It’s a deft and unexpected approach, diffusing narrative tension in favor of a more inchoate set of anxieties, which only expand the deeper we read. At the same time, this enables “One Friday in April” to move fluidly between recollection and reflection, between what happened and the questions it provokes.

“Is it logical,” Antrim asks, “to imagine that psychotic self-evaluations are cogent? The notion that we choose death over pain, fundamental to our current thinking on suicide, suggests that we choose at all, as if some part of us exists outside the illness, unaffected, taking in the situation and making rational decisions.”

What he’s saying is that, for the suicidal person, there is no cause and no effect, or not in the way we commonly think about it; there is just the habit of being. Such a perspective is both holistic and a fatalistic. The individual cannot be separated from either the situation or the act. “Must we distinguish between brain and body?” Antrim muses. “… Does my heart pound in anxiety, or am I anxious because my heart is pounding? Am I out of breath because I’m scared, or am I feeling scared because I am in cardiac and pulmonary distress?”

All of this comes together in his account of electroconvulsive therapy, which Antrim believes preserved his life. He consented to the treatment at the urging of David Foster Wallace, who had undergone ECT in the 1980s; Wallace insisted that it was “a safe and robust treatment, that the doctors knew what they were doing, and that I should not be afraid that I would lose my memory or competency.” The bitter irony is that Wallace himself would commit suicide in 2008.

His wife told Claremont police that the novelist and humorist who wrote ‘Infinite Jest’ hanged himself Friday night. He was 46.

Antrim’s writing here is brilliant in its indirection and compression. Because he receives general anesthesia, he is literally absent from the process, which he narrates in second person to highlight that interior distance. “The anesthetic trickles down the tube,” he writes. “You can smell it. It has a sweet smell. You count backwards, one hundred, ninety-nine, ninety-eight, and then the anesthetic reaches your blood, and a second passes, and you feel that you are falling — and then blackness.”

It’s a fascinating move in which the processes of healing cannot be represented or recalled. In the wake of this liminal experience, Antrim reaches not a conclusion so much as a way of thinking outside the binary. “As long as we see suicide as a rational act taken after rational deliberation,” he writes, “it will remain incomprehensible. … But if we accept that the suicide is trying to survive, then we can begin to describe an illness.”

So what is there in the end, if not resolution? A strategy for engagement, for reframing suicide as comprehensible — paradoxically — by rendering all our easy explanations moot. “The purpose of suicide is death,” Antrim insists, “not what we may think of as rage, revenge, or atonement for sin. To the extent that the suicide acts, it is but a falling away.” Suicide, in other words, is its own country, and we must approach it on its own terms.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.