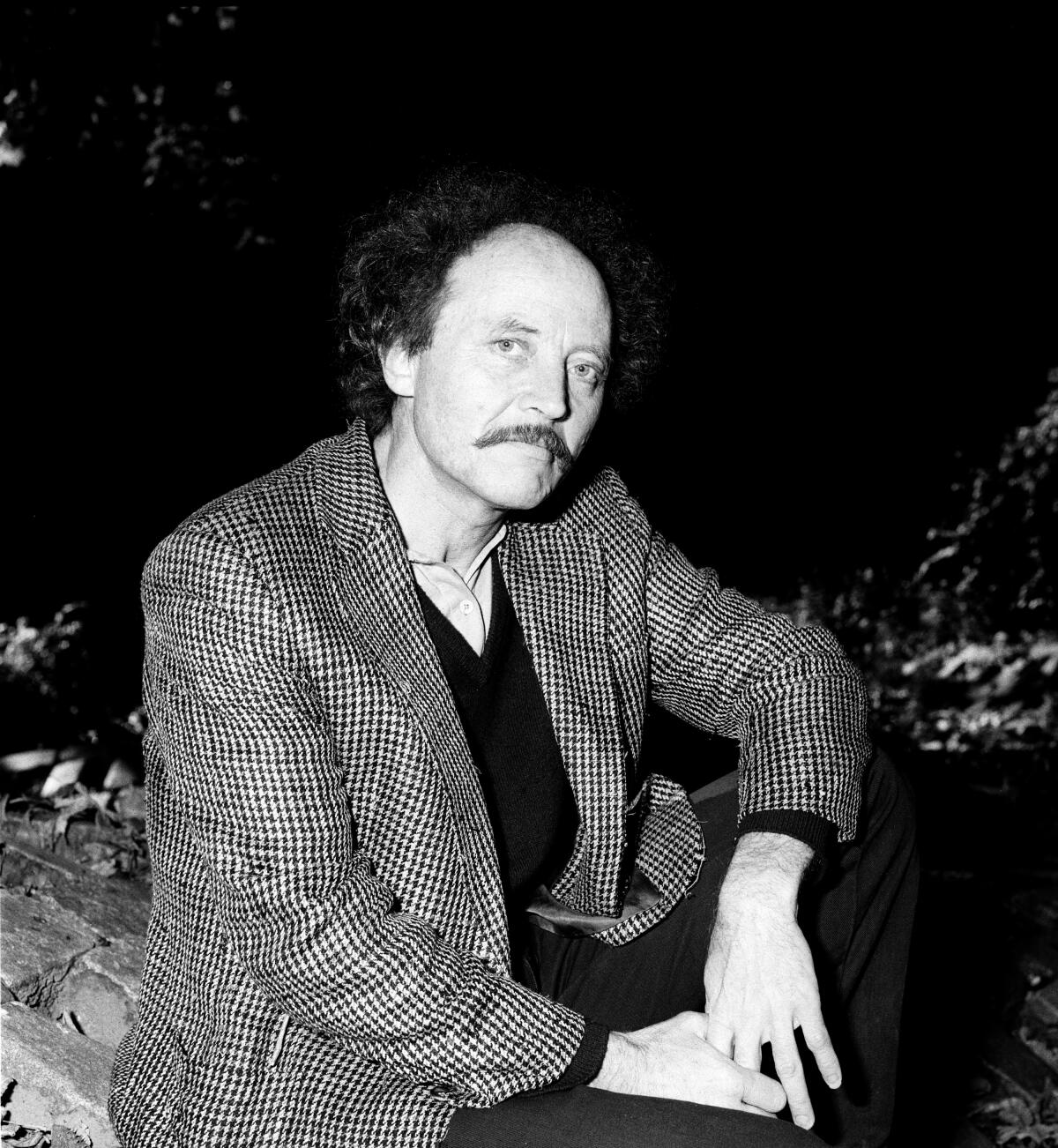

Appreciation: Sylvère Lotringer made book publishing safe for dangerous ideas

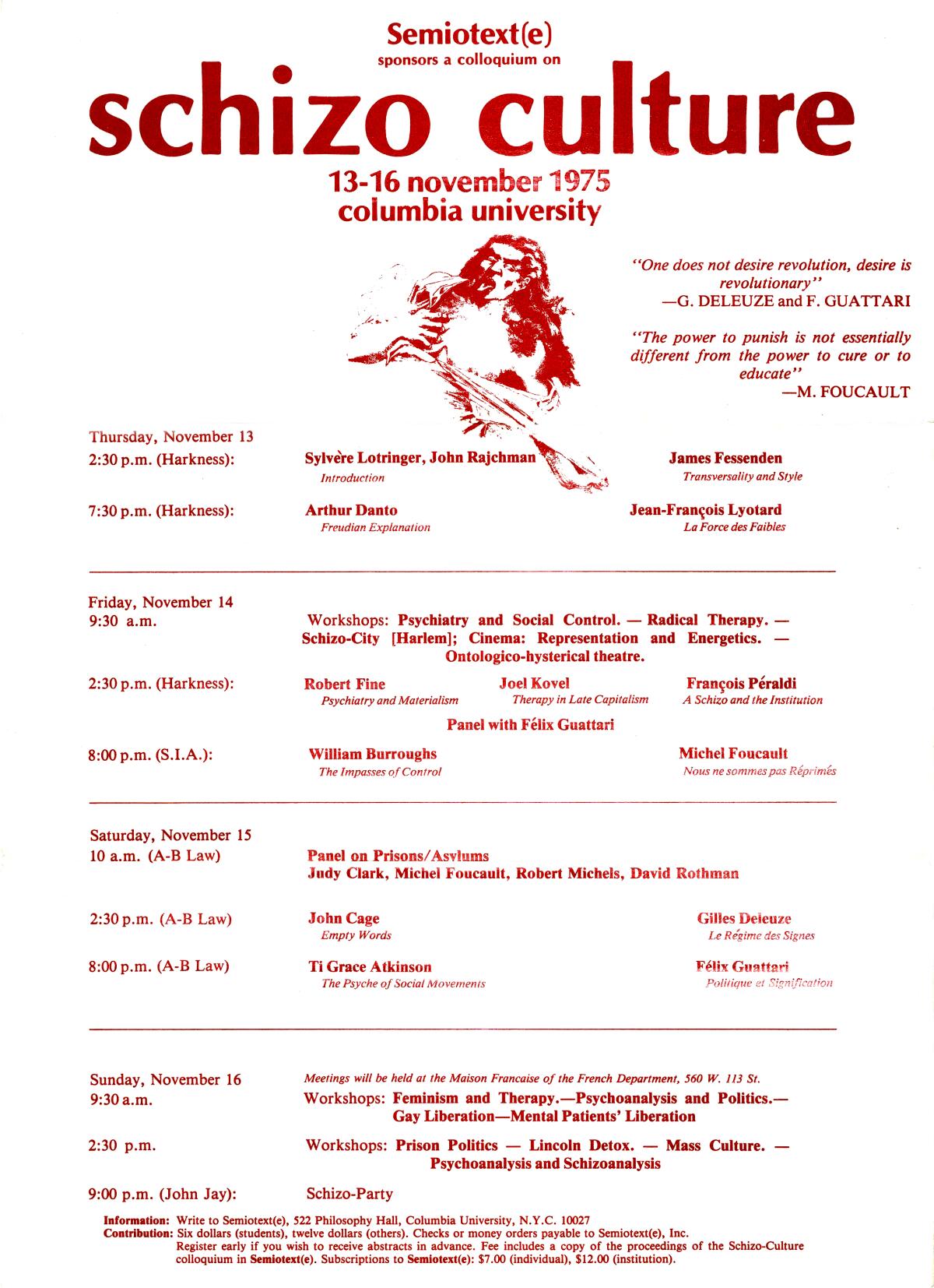

I never knew Sylvère Lotringer, although I admired him. By the time I started hanging around the fringes of the New York art and writing world, he had already removed himself from active involvement in the journal Semiotext(e), which he founded at Columbia University in 1974. I was aware of the basic narrative, which began with the Schizo-Culture conference Lotringer had organized in 1975, bringing together French semioticians with Manhattan scenesters: Michel Foucault and William S. Burroughs, Gilles Deleuze and John Cage. Two years later, the event—a chaotic cultural free-for-all—was commemorated in a special issue of “Semiotext(e).” After all this time, it remains an exhilarating reminder of the kind of ferment a publication can provoke.

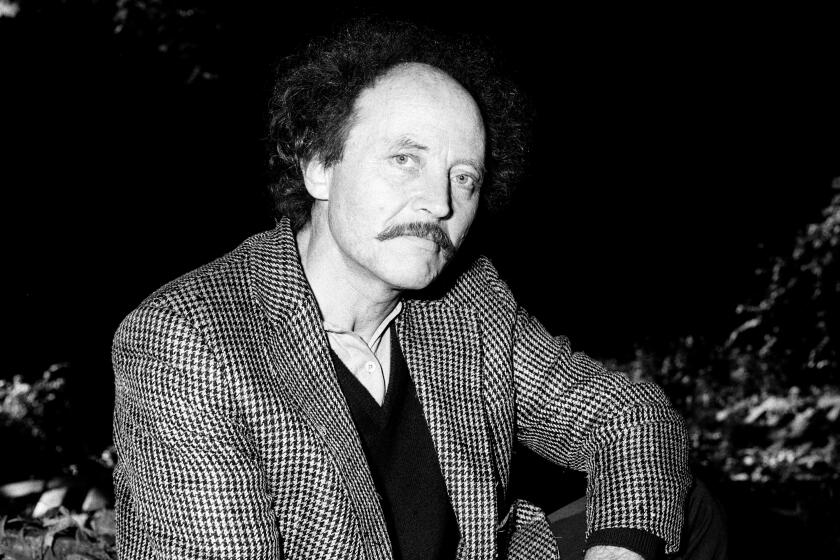

Semiotext(e) was all about those sorts of provocations, whether as a periodical — issues continued to appear sporadically into the 1990s — or as the independent publisher it became. By the time Lotringer died on Nov. 8 in Mexico at age 83, he had seen his anarchic project evolve, unexpectedly, into an institution: innovative, confrontational, gleefully anti-commercial. “Never give people what they want,” he once observed, “or they’ll hate you for it.” That might have been a mission statement or a manifesto, so perfectly did it evoke the flavor of his work.

Lotringer was best known as the founder of the influential magazine Semiotext(e) — as well as for being name-checked in Chris Kraus’ ‘I Love Dick.’

That work included writing — Lotringer was the author of books and monographs about Antonin Artaud, Nancy Spero and David Wojnarowicz, among others — and also editing; he launched Semiotext(e)’s Foreign Agents book imprint in 1983. The impetus was twofold: to introduce French theorists to American readers (the first title was by Jean Baudrillard) while also stripping away the critical apparatuses that fenced in — or tamed — incendiary ideas.

“Footnotes or other academic commentary were conspicuously absent,” Lotringer would later recall. “Their place was in the pockets of spiked leather jackets as much as on shelves.” This was publishing, to borrow a phrase from the Scottish novelist Alexander Trocchi, as “the invisible insurrection of a million minds.”

I was one of those leather-jacketed readers, with little interest in the mechanics of the academy. Those small and slender Foreign Agents titles struck me with the force of secret messages, inscribed in a language I was desperate to understand. My favorites overlapped my fascinations: Derek Pell’s “Assassination Rhapsody,” an absurdist deconstruction of the Warren Report; and “Behold Metatron, The Recording Angel,” by Sol Yurick, best known for his novel “The Warriors,” which portrayed a phantasmagorical New York beset by cultish gangs.

Published in 1985, “Behold Metatron” was more a book of reflection than of narrative, a nonfiction work that offered a prescient vision of a world transformed by data. “The old philosopher’s stone,” he wrote, “could convert base metals into gold. Now humans, real estate, social relations are converted into electronic signs carried in an electronic plasma. The dream of magical control has never been exorcised.”

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

Like Yurick, Lotringer was smart enough to remain a moving target. In 1990 he again expanded Semiotext(e) with the Native Agents series, which he co-edited with his then-wife, the writer Chris Kraus. Among the titles they showcased were Cookie Mueller’s “Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black” and Ann Rower’s magnificent “If You’re a Girl.” These remain among the most transcendent and transgressive works of personal narrative I know.

“It seems weird how all the embarrassing female type stories seemed to be popping into my mind, and then my writing,” Rower confesses on the first page of her book. “… I want to make a collection of them and call it ‘If You’re a Girl.’” It’s a meta moment, or it would be, except that Rower has no interest in that sort of game. When a friend asks if her book will be about pre-pubescence, she goes “immediately on the defensive”:

“No, I said, … it’s, you know, a state of mind.”

With this voice, offhand yet also pointed, Rower highlights the impulse behind Native Agents, which Kraus would describe as “a new form of female subjectivity.” That this echoed — or mirrored — the work of the postmodernists was part of the point, a strategy for putting their radical notions of subjectivity into play outside the walls of the academy. Perhaps the apotheosis of such an aesthetic is Kraus’ 1997 epistolary autofiction “I Love Dick,” originally published as a Native Agents title and later adapted for Amazon TV. The irony of that move, from Semiotext(e) to Amazon, edge to center, only validated the imprint’s sensibility, its intent not only to blur but also actively to eradicate the lines. Theory, personal narrative, television — they were all part of the cultural landscape, available to be appropriated, mashed up, mixed and matched.

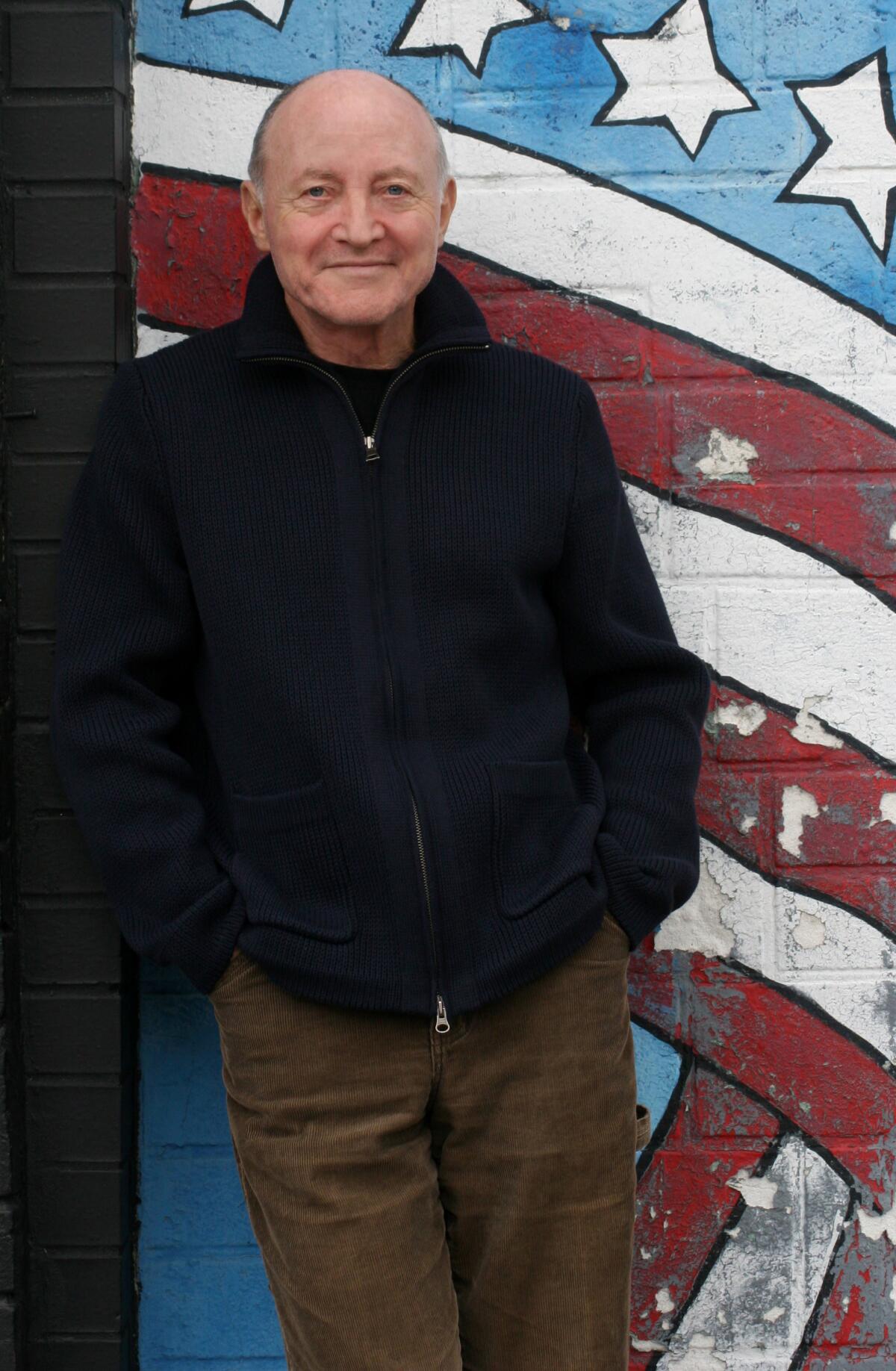

Lotringer understood this. He saw art-making as a collective practice in which collaboration can yield unexpected results. This meant letting others edit the journal: Jim Fleming, whose Autonomedia imprint distributed Semiotext(e) books for more than two decades; Peter Lamborn Wilson, who, in his 1991 exegesis “T.A.Z.,” developed the idea of the temporary autonomous zone, a liberated area (Burning Man is one example) that allows us, for a moment anyway, to push back against the hierarchies of control. The issues they helped put out, particularly “Semiotext(e) USA” (1987) and “Semiotext(e) SF” (1989), remain exhilarating in their resistance to convention, their intention to enflame. Kraus became Semiotext(e)’s co-editor, in a partnership that outlasted the marriage, and in 2001 she and Lotringer moved to Los Angeles, where they reinvented once again.

Jill Soloway and Eileen Myles are no longer together, they revealed from the stage at the Billy Wilder Theatre at the Hammer Museum on Wednesday night.

In the aftermath, I lost track of Lotringer, although many of the books he edited continue to occupy my shelves. Lynne Tillman, David Rattray, Eileen Myles — these and other writers changed how I thought of narrative and publishing and the ways an artist navigates the world. Something similar might be said of Lotringer, who had an imagination and a vision large enough to encompass them all. “At this point,” he said in 2015, “the art world is hardly different from any other corporation, except that it is more directly enmeshed with finances. It has created for itself a world of glamour and luxury unequalled anywhere else.” Yet rather than despair, he considered this an opportunity: “Resistance,” he concluded, “begins at home.”

Ulin is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.