Gary Shteyngart’s cozy, dystopian, soap-operatic immigrant COVID paradise

On the Shelf

Our Country Friends

By Gary Shteyngart

Random House: 336 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The fall leaves were turning, the sweater weather brisk, and I was waiting for Gary Shteyngart in front of a popular restaurant in Hudson, N.Y., to talk about his new book, “Our Country Friends.” The novel features a Shteyngart-esque writer, Sasha Senderovsky, his family and friends, a famous Actor, a Hudson Valley compound and, last but not least, the pandemic.

Shteyngart had described himself over email so I could spot him: “small, furry and have a confused expression on my face most times.” Facing away from me, wandering around a vintage clothing rack, was a short man with a halo of chaotic gray hair. As I started toward him, the real Shteyngart came up from the opposite direction. Trim, well-groomed, sharply dressed and wearing the kind of watch that watch people apparently notice, here was Shteyngart the author. The man who had manifested as Senderovsky wandered off.

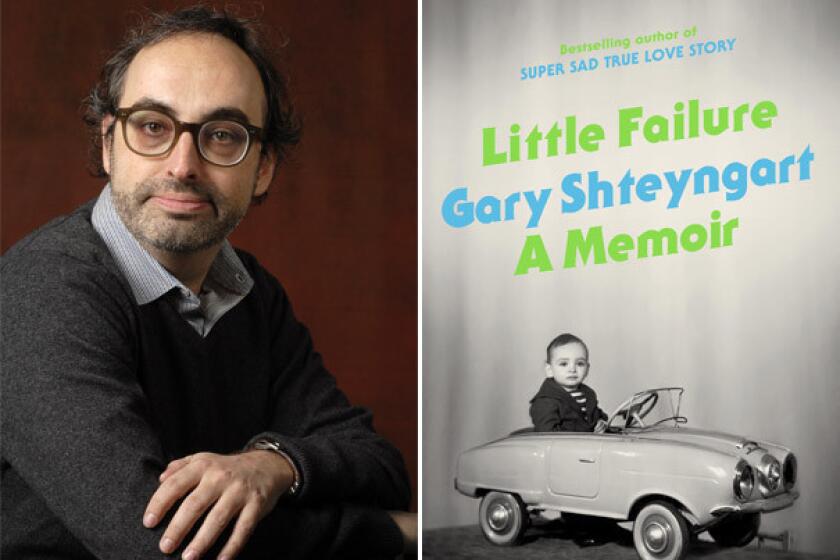

And yet Shteyngart says Senderovsky is his fictional avatar. Senderovsky lives in a home much like Shteyngart’s in the Hudson Valley; they both have a sheep farm nearby, a few right-wing neighbors and a groundhog called Steve. They’re both married with a school-age child. But Senderovsky’s career is in trouble, unlike Shteyngart’s. The real author’s bestselling books include the novels “Absurdistan” and “Super Sad True Love Story” and the memoir “Little Failure.” Funny, melancholy and often socially prescient, they are acclaimed for viewing the American condition through a lens that’s uniquely askew.

“Nobody reads Senderovsky anymore. He’s kind of a done deal,” Shteyngart said. “Maybe one day I’ll be too. Maybe this will be the time, maybe this is the end.” At our outdoor table, he was speaking in a rush, jokes and serious ideas jostling one another. He took a sip of his cocktail — we’d ordered cocktails with lunch, in the spirit of the book’s boozy retreat.

“I love people who are still trying to negotiate any kind of relevancy for themselves,” he continued. “Writers, like ballerinas and artists, have to have an expiration date. Then it’s somebody else’s turn. Unlike Senderovsky, I have a nice tenured job at Columbia, so I’ll never be on the street. Which is the ultimate immigrant thing.”

Russian-born American writer Gary Shteyngart delivers the memoir ‘Little Failure,’ in which a would-be maudlin childhood becomes an ecstatic depiction of survival, guilt and perseverance.

As his biography still notes, Shteyngart was born in Leningrad in 1972. He grew up in Queens in a community of immigrants; the characters in the book come from South Korea, Russia and India. Decades later, their friendships aren’t about where they came from but their shared American history. As they recount their sometimes conflicting memories of roommates, an unfulfilled crush, ups and downs and that one unforgettable party, the past bleeds into the present.

Shteyngart, who is eager to point to real-life inspirations for his fiction, advisably brushed off questions about these characters. Each is based on several people, he said, although I’m not entirely sure I believe him.

At midlife, one is recently a tech millionaire, another a jet-setter with inherited wealth; Senderovsky has been a success but faces failure. The last of the dear friends is a failed adjunct professor working at his uncle’s restaurant.

“I think all the other immigrants feel very guilty about what happened to him and think, is it patronizing to want to help him? What can we do for him? He’s the cross that they all bear,” Shteyngart said. “So many immigrants aren’t successful. We hear only about the Sergey Brins.”

Senderovsky’s friends are all invited in the spring of 2020 to wait out the pandemic at his home in the country. He’s also invited a former student starting a slightly troll-y career, as well as the handsome, famous (unnamed) Actor, who’s attached to the TV deal Senderovsky desperately needs to happen. (In case you’re inclined to confuse this aspect of Senderovsky with Shteyngart, the real author consults for “Succession” and has projects in development — and the Actor is too old to be based on his former student James Franco.)

“Our Country Friends” has all his usual humor and absurdity, but it’s deepened by a new empathy. Seeing things from different characters’ points of view helps; Shteyngart toggles among them smoothly and rapidly, sometimes in a single paragraph. In addition to the lifelong friendships, there are sexy and awkward liaisons, blossoming love, secrets and betrayals. “The main thing I was reading when I was writing was Chekhov,” Shteyngart said. “Everyone’s in the countryside and voicing regrets about what happened, and they’re all in their middle age, if not older. They’re like, ‘I wanted this, but I became that.’”

Braced by the cocktail, I asked Shteyngart a question I’ve never asked an author before: “So … how’s your penis?”

In a recent issue of the New Yorker, Shteyngart wrote about the ordeal of having a botched circumcision at age 7 after his family moved to America. The “covenant of pain” culminated belatedly, during the pandemic year of 2020, in a cascade of crises he describes in the essay in excruciating detail.

“Thank you for bringing it up,” he said. “It’s interesting. Some interviewers are interested, and others are studiously avoiding the question. There’s no pain anymore. There’s just a discomfort. It sends signals every once in a while. It says, ‘Hi, you’re Jewish.’”

If anyone can teach you writing, maybe George Saunders can?

I’m fascinated by his generation of Russian-Jewish-American writers. I tell him I remember seeing banners in Los Angeles in the 1980s imploring us to “Save Soviet Jewry” by helping his people immigrate.

“It was really nice for them to do that. On the other hand, the month after I came here, I had a part of my penis cut off,” Shteyngart said. “Getting me out of the Soviet Union was nice; the genital mutilation, not so nice.”

I laughed. “You’re making me laugh at your pain,” I said. “I’m sorry.”

“That’s all I do as a writer,” he replied.

He was undergoing terrifyingly painful treatments when working on “Our Country Friends,” with a side of hallucinations. These made their way into the text: In addition to typical Shteyngartian scenes, like an unsexy hookup at an abandoned children’s camp, there are some surreal visions and nightmares. There is darkness in this story — which is, on the whole, a happy, sylvan version of the pandemic.

“Being here was a privilege, an absolute privilege,” said Shteyngart, who usually spends most of his time in New York City. “The guilt that all the characters feel comes from a very personal place. I grew up in Queens, where all of the horror was happening.” For a time, New York City’s most diverse borough was also the nation’s epicenter of COVID-19 fatalities. “That’s where all the characters are from. That’s where half of my best friends are from.”

The contrast in the novel between Queens and what he’s called his “dacha” was no accident. “It’s class. It’s ethnicity and race. All of these things obviously play a role in who gets to survive a pandemic in America.”

Neither is the Hudson Valley a never-ending idyll. Throughout our lunch, our table was plagued by yellow jackets. They came for the fruity cocktails, stayed for the mapo tofu and the fried chicken. Shteyngart put down a plate and accidentally murdered one. Another drowned in a water glass. When we left, the waitstaff told us they hoped the yellow jackets would go with us, because they hadn’t been bothering any other tables.

It felt a little accusatory, as though the neurotic author and critic had manifested the wasps. It was surreal and improbable and a little bit absurd — a moment worthy of Gary Shteyngart.

Coming in November: Sam Quinones, Ann Patchett, Emily Ratajkowski, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Gary Shteyngart, Natashia Deón — and the list goes on.

Kellogg is a former book editor of The Times. She can be found on Twitter @paperhaus.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.