Review: Author Karl Ove Knausgaard, famously extreme realist, goes supernatural

On the Shelf

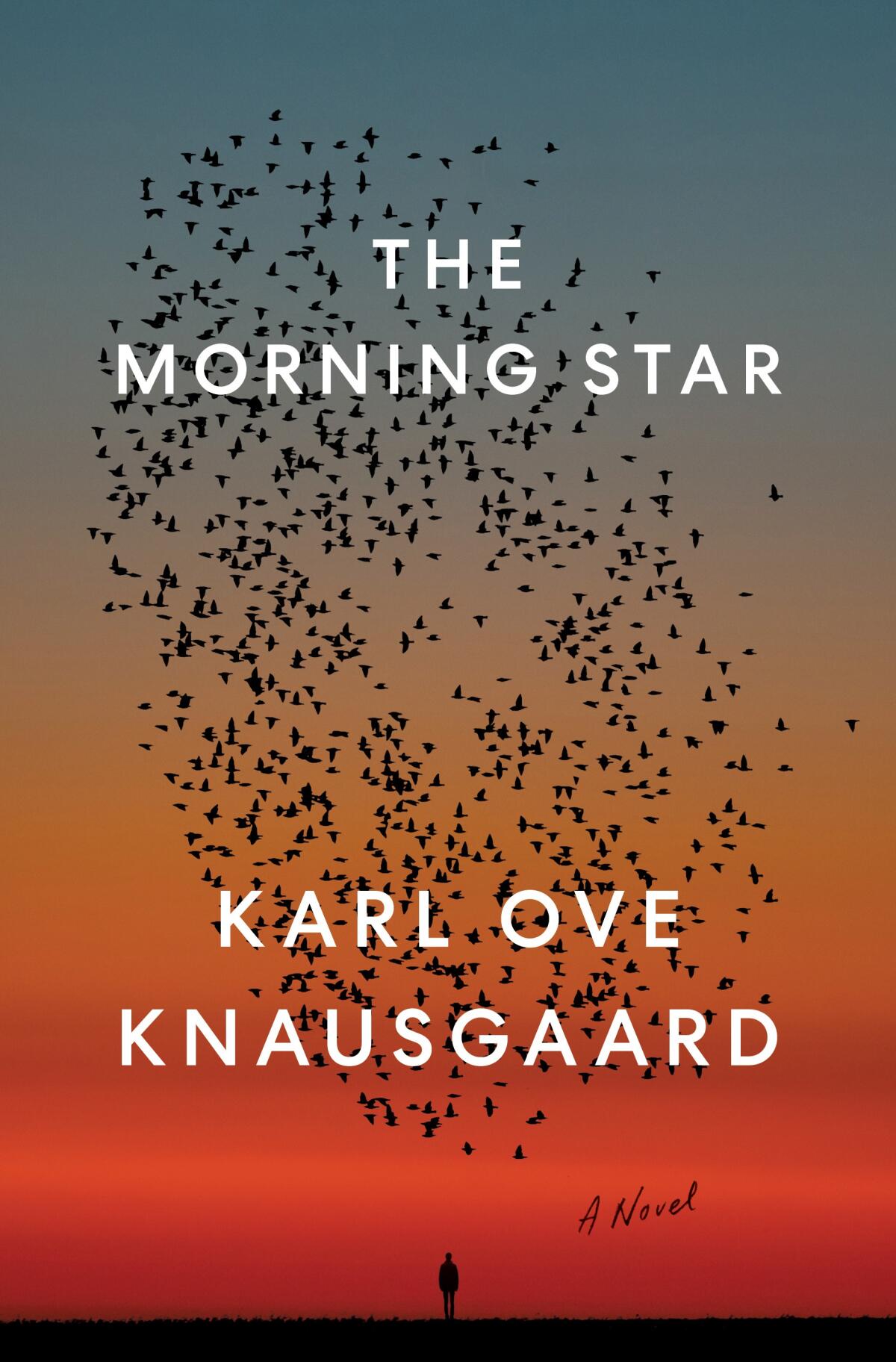

The Morning Star

By Karl Ove Knausgaard

Penguin Press: 688 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Perhaps it’s a coincidence that Karl Ove Knausgaard’s new novel ends on page 666, but don’t bet on it. “The Morning Star” finds the bestselling Norwegian author in strange and unsettling new territory. At first, it seems familiar: As in his great six-volume autobiographical novel, “My Struggle,” major subjects include bourgeois anxiety and malaise, the stock-in-trade of middlebrow fiction. This time, however, we see them through a glass darkly, and as the pages turn, “The Morning Star” reveals itself to be the evil twin of “My Struggle.” It’s an uncanny, polyphonous, diabolical work that gives Knausgaard’s brand of banal realism a mythical-fantastical twist.

The action takes place over two late-summer days around Bergen, Norway. It’s “hot as hell”; lawns are “yellow and parched”; catastrophe feels imminent. Arne’s artist wife Tove is having a psychotic break; Kathrine, a priest, is questioning her tepid marriage; Turid, a nurse, works nights on a psychiatric ward while her unfaithful husband, Jostein, drinks and rails against an unfair world. Knausgaard’s nine narrators are all working through something: alcoholism, career disappointment, crises of faith and despair.

Meanwhile, a giant new star has appeared in the sky. Is it a supernova? A biblical portent? “Something terrible was going to happen,” thinks Kathrine. “It’s only Armageddon,” says Jostein. “It had to come sooner or later.” Connected, perhaps, are the erratic behavior of Bergen’s animals and sightings of monstrous figures — half-human, half-beast — in the woods. Sinister irruptions, bad omens, visions of fire: Is something evil going on? Are the dead really dead?

“In the Land of the Cyclops” is the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard’s first essay collection in English, a refreshing shift from his epic, “My Struggle.”

While the domestic hallmarks of his recent fiction — doing the dishes, kids squabbling over iPads — remain intact here, Knausgaard also mixes in both strong elements of horror and some of the more grandiose religious themes of “A Time for Everything,” his early novel about angels. In doing so, he reveals himself to be a surprise master of the uncanny. We see a cleric forced to bury the double of a man she just met; an organ donor, dead on the operating table, whose eyes open...

Big swaths of the novel take place in the liminal spaces between consciousness and sleep, drunkenness and sobriety, life and death. Our narrators lose concentration; they only half-sense things. A dead kitten seems still to be warm. An enormous bird in the woods appears to bear a child’s face. Knausgaard gradually induces in the reader the same kind of discombobulation by having different plot lines run at different rates. As they slip further out of joint, any impression of simultaneity or normal chronology is subtly but deliberately undermined.

As longtime fans might expect, behind the prose lies a wealth of hardcover learning, from the Bible and the Augsburg Book of Miracles to Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Heidegger. Lars von Trier’s films seem to be an influence, particularly the unpleasant “Antichrist” and the depression-disaster epic “Melancholia.” Dante is a key touchstone too, from linguistic echoes — hot weather is, naturally, an “inferno” — to the way someone flushes the toilet in order to watch it “all whirl away into the underworld.” In a delirious late chapter, one of our heroes drinks from the river Lethe and loses his memory (as in the “Purgatorio”).

And although Dante’s religious crisis is transposed here into a series of late-capitalist midlife crises, at least some of Knausgaard’s characters are humble in the face of the unknown, acknowledging the gulf between what we believe and what we know. At the end of the novel comes a long essay concerning beliefs about death in different civilizations, deepening Knausgaard’s theme (if not quite successfully integrating it into the narrative).

The putative author of that essay, Arne’s neighbor Egil, is the character most in tune with the metaphysical heart of the book, speaking to the author’s darker philosophical purpose: “[T]he world is the physical reality in which we live, whereas our reality is in addition to everything we know, think and feel about the world. The point being that the two layers are quite impossible to tease apart. The kingdom of the dead was once a part of our reality. But it’s never been a part of the world.”

Daniel Loedel’s ghostly debut novel, “Hades, Argentina,” features an exiled resistance fighter who revisits crimes, including his own, in Buenos Aires.

The storytelling gift that kept readers enthralled by “My Struggle” remains powerful. Like Stephen King, another inspiration here, Knausgaard stays shoulder-close to his characters, his paragraphs mimicking the erratic interleaving of their thoughts. And they all give good copy because, in all their mean-spirited, shame-filled, petty glory, Knausgaardian archetypes are nauseatingly compelling. Perhaps the best, most unpleasant variant here is Jostein, whose misanthropy emerges on a bender that tallies, at a rough count, 10 beers, six Jägermeisters, four glasses of wine, two vodka Red Bulls, two gin and tonics and a whiskey. “No one could ever tell how drunk I actually was,” he boasts. “It had to be one of my most useful talents.” (He’s wrong, of course.)

In places, “The Morning Star” may feel too close to Knausgaard’s previous work. The marriages and parental conflicts are in the same key as “My Struggle” — some details of Tove’s mental breakdown directly mirror Linda’s in Book 6 of the earlier series. And Knausgaard’s odd decision not to try too hard in distinguishing between the voices of his narrators has the consequence that they all sound more or less like him. “Everybody knows I’m writing it anyway, so why should I pretend like I’m not?” he remarked in a recent Vulture interview. Hundreds of pages in, as new characters continue to be introduced, readers may crave some variation.

Knausgaard said in the same interview that “The Morning Star” is the start of a new series — and indeed, a late cliffhanger leaves many doors open. So perhaps it’s premature to examine the shape of the book. Even so, the write-now, edit-never approach doesn’t seem wholly successful. At times, the novel feels like a collection of short stories hastily sutured together with a supernatural plot device. Nevertheless, Knausgaard remains a writer of supreme interest. This is a thoughtful, highly readable novel, packed with ideas and exciting flourishes. And in any case, his rate of production is such that a year from now, we’ll already be poring over Volume 2, reassessing everything we thought about the first one.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

Arrowsmith is based in New York and writes about books, films and music.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.