Stargazing across millennia in ‘Universe: Exploring the Astronomical World’

Enclosed in total darkness, save for the soft outline of our own blue planet curving far below, a man in a puffy white space suit free-floats through space. The black is so deep and endless, and the earth from that vantage point so alien, that he looks positively inconsequential. He could be a bug.

The image isn’t a still from a science fiction film but a NASA photograph of “Bruce McCandless on Untethered Spacewalk” taken in 1984 before the Manned Maneuvering Unit — a veritable jet pack — was discontinued due to its obvious risk. The photograph is profoundly evocative of humans’ relationship to space — our vulnerability, our willful exploration. In “Universe: Exploring the Astronomical World” it joins other such images of the cosmos — some just as literal, others acts of imagination — created over millennia.

Chosen by astronomers, astrophysicists, curators and art historians, the book paints a broad portrait of the ways human beings have studied, interpreted and depicted the universe. “ ‘Universe: Exploring the Astronomical World’ reflects all aspects of that exploration, from the mystical and religious to the purely scientific, the aesthetic, the symbolic and even the psychological,” writes astronomer Paul Murdin, consulting editor, who discovered the first stellar black hole in our galaxy in 1971.

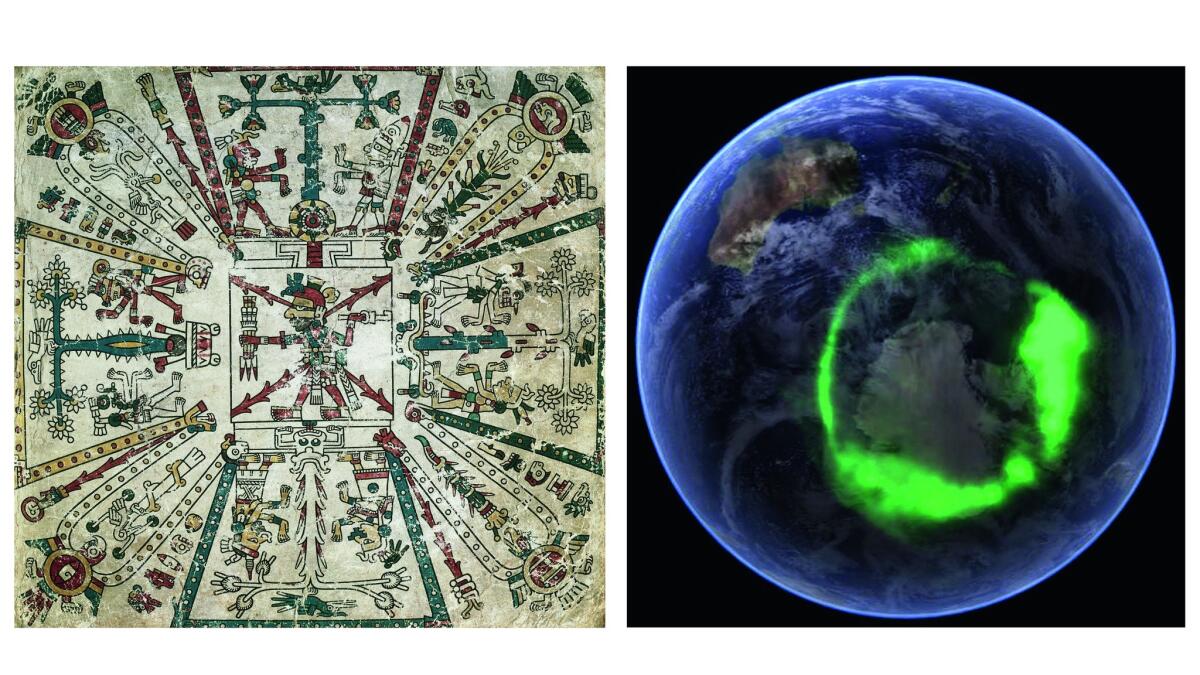

Digital photographs, medieval manuscripts and contemporary art have all tackled this giant subject, and “Universe” includes examples of them all. (As such, it’s as heavy as a meteorite: a big book, for a big topic.) Moreover, explains Murdin, “rather than being arranged chronologically or thematically, the book pairs complementary or contrasting pairs of images to underline continuity, innovation and change.”

Gathered from across the globe, and toggling between various mediums — satellite photographs, modern sculptures, antique engravings — “the images collected … strongly contradict the idea that there is a division between ‘scientific’ and ‘artistic’ depictions of space.”

An Alma Thomas painting titled “Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset” looks straightforward, composed of red, yellow and orange like any literal rendition of a sunset might be. But as it turns out, “Snoopy was the call sign of the lunar module of Apollo 10” as well as the Peanuts cartoon character. Similarly, Katie Paterson’s “Totality,” which on first inspection appears to be an average disco ball, is actually “inlaid with mirrored tiles reproducing almost every solar eclipse documented in human history — more than 10,000 images total.”

Circles recur for obvious, planetary reasons, but so do color, light and awe. A NASA digital photograph of the Southern lights is rich and precise and beautiful; an illustration of a comet in the circa 1550 Augsburg Book of Miracles, which was thought to foreshadow calamity and punishment, may not capture that cosmic event with NASA’s same accuracy, but its elegance is undiminished today.

“As we have learned more about [space] physically, we have also come to interpret it in different ways,” writes Murdin. The telescope, the camera and the rocket ship may have transformed the way that we record the final frontier, but in spanning centuries of work “Universe: Exploring the Astronomical World” reminds us that even our current capacity is limited. These images “are all in their own way records of the same quest: that of understanding the heavens and what they tell us about ourselves.”

“Universe: Exploring the Astronomical World”

Paul Murdin, consulting editor

Phaidon: 352 pp., $59.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.