Richard Wright’s newly uncut novel offers a timely depiction of police brutality

On the Shelf

The Man Who Lived Underground

By Richard Wright

Library of America: 240 pages, $23

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Many readers know about Richard Wright’s famous 1940 debut novel, “Native Son,” about a 20-year-old Black man who can’t escape a system designed for him to fail and accidentally kills a young white woman as a result. Long considered a pioneering work of African American literature, it was also thought to suffer from constraints on what an author could really say — or be allowed to publish — in Jim Crow America.

Fewer readers know that, in 1942, Wright submitted to his publisher a considerably more radical work. “The Man Who Lived Underground” follows Fred Daniels, a Black man who retreats into the sewers after being tortured by police and framed for a double homicide.

At the time, publishers believed white readers didn’t want to be reminded of America’s history of violence against Black Americans. They wanted something more along the lines of “Native Son,” which sold 215,000 copies in its first three weeks of publication, making Wright America’s leading Black author.

“[‘Native Son’ depicted] Black on white violence or Black on Black violence,” said Library of America editorial director John Kulka. “But white on Black violence was different. We can imagine [publishers] had more difficulty with ‘The Man Who Lived Underground’ and its graphic depictions of police brutality.”

Across nearly 50 pages in the book’s opening chapters, Wright detailed explicit violence by police against a man who eventually confesses to a crime he did not commit. In the 1940s, that made parts of the novel untouchable. Kerker Quinn, the editor of the small literary magazine Accent, called the early chapters “unbearable.” Wright’s publisher, Harper & Brothers, rejected the typescript. It wouldn’t be published in its entirety until this month, nearly 80 years later, in a new edition from the Library of America.

“It just seemed such a departure from ‘Native Son,’” said Kulka, adding that Harper “simply did not recognize ‘The Man Who Lived Underground’ as a worthy successor. They were looking for another substantial work of literary naturalism, not a weird, short, allegorical novel about a man who flees into the city sewers.”

In a companion essay to the novel, Wright said he considered it to be his finest work, written “in a deeper feeling of imaginative freedom” and flowing more completely “from my own personal background” than anything else to date.

But after being turned down by publishers, the author published a truncated version, which appeared first in the 1944 anthology “Cross-Section: A Collection of New American Writing” and later in the posthumous 1961 collection “Eight Men.” Accent also published two excerpts from the story. Excised were the violent first section and parts of the ending that were considered too dark.

Readers had to wait another half-century for the Library of America, a nonprofit that publishes classic American literature in authoritative new editions, to release an unexpurgated version. The story appears alongside an unpublished essay, “Memories of My Grandmother,” which Wright intended as either a preface or afterword.

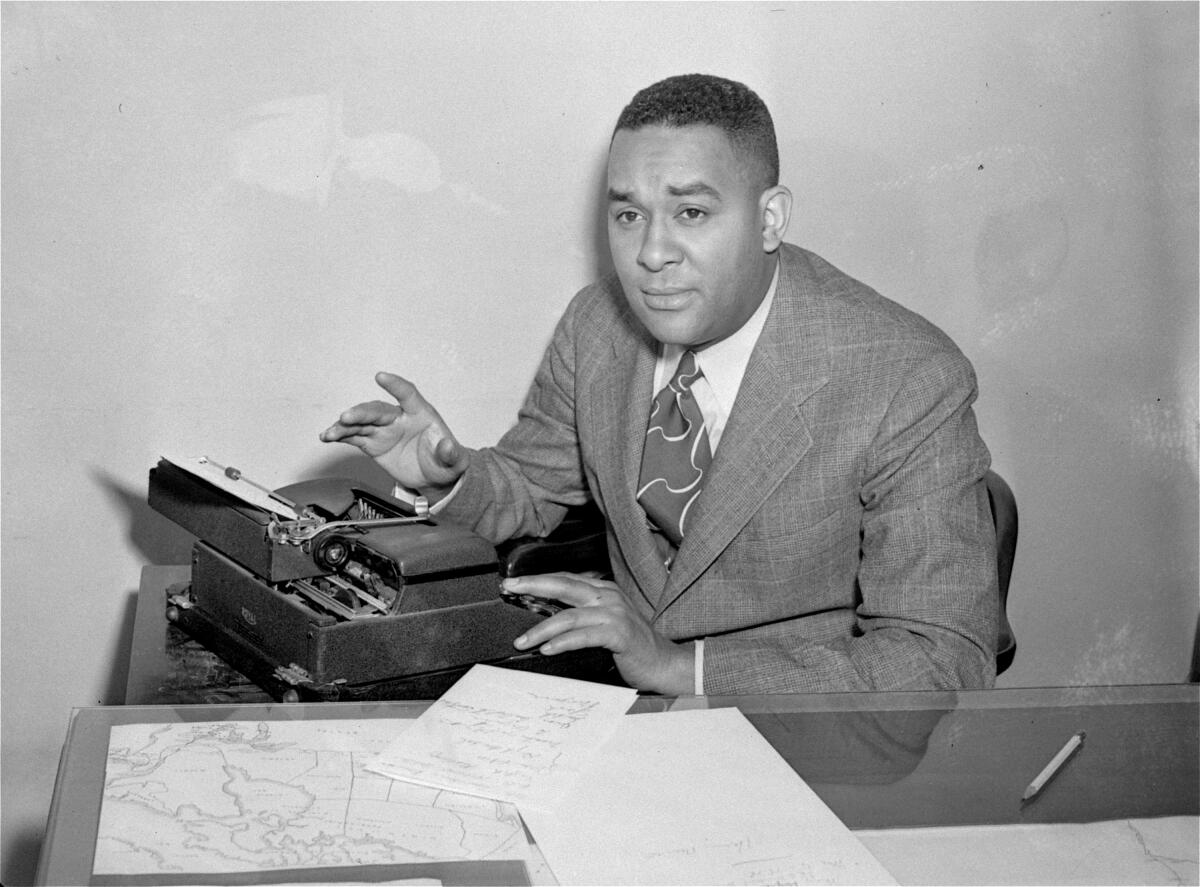

In 1940, Richard Wright published the social protest novel “Native Son,” about one man’s doomed attempts to rise above the racist structures that bind him.

The publisher had restored Wright’s earlier works (which had also been abridged) in a two-volume edition published in 1991. A few years ago, his daughter Julia Wright reached out to the Library of America to see if they could do something similar for “The Man Who Lived Underground.”

“She had been going through the Richard Wright archives at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale,” said Julia’s son, Malcolm Wright, who wrote the new edition’s afterword. “She was having one of those kid-in-a-candy-store moments because it’s just endlessly fascinating to go through all those materials.”

When she came across the original version of the story, “she immediately felt that the world should never have been deprived of it,” said Wright. “It was long overdue.”

It took Library of America editors years of painstaking study of archival typescripts and letters to establish a final edit for the novel based on Wright’s last complete working draft. “They’re extremely careful and meticulous in examining every word of every manuscript when they’re publishing” something new, said Wright.

The decision to release an expanded version came in 2017, years before the Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death. “My mother had long been involved in issues of police brutality,” said Wright. “So she [thought] ‘This is something that we as a family can do to help raise the profile. Little did she know that it would take several years for the project to come to fruition and that by the time the book was out, the country would have begun to take a closer look at all of this.”

“She was really the catalyst behind this project,” said Kulka. “She had recognized long ago the importance of the novel-length version with its graphic depictions of police brutality and also the novel’s artistic merits apart from those of the short story.”

Wright says the expanded version helps contextualize his grandfather’s eventual decision to move his family abroad, away from the American criminal justice system.

“He was already contemplating: How do I bring a Black child into [this world while living] in the United States? As somebody who had already left the South for the North, he’d already demonstrated a capability to peel back a layer of reality and choose something different for himself. And so he left [America] to give a different future to his family. So you get a foreshadowing within his creative work of standing on the brink of doing something momentous.”

Both “Native Son” and Wright’s autobiography, “Black Boy,” were abridged by his publisher and the powerful Book of the Month Club.

Wright was the first Black writer to have his books selected for the club but only on the condition that he heavily redact language they believed was offensive. “Book of the Month Club had the ability in those days to catapult a book onto the bestseller list,” said Kulka. “It was an offer he couldn’t refuse.”

“Native Son” also contained graphic depictions of violence, some of which were cut by his publisher. Five years later, “Black Boy” was published — not rejected like “Underground” — but cuts were nearly as severe as those that dismembered the latter into stories. Wright was asked to drop the entire second half of the memoir, which detailed his involvement with the Communist Party in Chicago. (The Library of America restored the excised material in both “Native Son” and “Black Boy” for its 1991 edition.)

Memoirs by Kiese Laymon and John Edgar Wideman; essays by Darryl Pinckney and Mikki Kendall; masterpieces from Michelle Alexander and Claudia Rankine.

Now that the work has been restored, a clearer thread can be traced between Wright’s works. “I call it a bridge book between ‘Native Son’ and ‘Black Boy,’” said Marcus Anthony Hunter, a professor of African American Studies at UCLA, of the newly released novel. “I appreciate it as intellectual reparations for Richard Wright because it gives a fuller understanding of his writing agenda. It helps make sense of his creative trajectory.

“You have ‘Native Son,’ about a Black kid who kills a white woman, and then ‘The Man Who Lived Underground,’ where he didn’t do it,” Hunter continued. “I think Wright very intentionally followed ‘Native Son’ up with a Black man being framed for a crime he did not commit. And then followed [that] up with a memoir as a Black man in America who lives as if his existence is a crime. So I see it as a very specific anchor that makes his creative genealogy make sense.”

Kulka calls the novel “a missing link between ‘Native Son,’ a work of literary naturalism, and [1953’s] ‘The Outsider,’ another allegorical novel. And it changes the way we see some of Wright’s friendships and the relationship of this story to others.”

He cited a 1942 congratulatory note sent by novelist Ralph Ellison to Quinn for publishing Wright’s short story in Accent. “I think the novel-length version reveals its influence on Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man,’ another novel with an underground protagonist,” said Kulka. “The words ‘invisible man’ appear in the [Underground] typescript, and Wright discusses at some length in the companion essay the influence of the ‘Invisible Man’ movies.”

Linking Wright and Ellison might also help amend the critical consensus that cast the former as a transitional writer (James Baldwin condemned “Native Son” for perpetuating stereotypes). But never did Wright approach race more directly than in “The Man Who Lived Underground.”

“Fred goes from being at the mercy of these police officers, who can do whatever they please with him, and he descends into the sewer, which is a kind of further debasing,” said Malcolm Wright. “And yet through that process, he starts to grow into something more than himself ... he transcends the barriers of what’s expected of us.”

As the trial of Derek Chauvin continues, the book’s exploration of police violence feels freshly radical and urgent. “He could’ve written those pages for today,” said Wright. “These are scenes that we’ve been done a real disservice for not having been exposed to earlier. The overt confrontation of our race relations has been lacking in our culture for so long.”

“I think an easy argument can be made that nothing has changed [since the 1940s],” said Hunter, the UCLA professor. “The one thing that has changed is that this book gets to exist now while it didn’t then, and maybe that will help us make the future that we all need.”

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.