A Mexican American professor who struggled with impostor phenomenon helps others overcome it

The walls of office No. 311 at Loyola Marymount University‘s College of Business Administration are covered with diplomas and awards. They symbolize the many achievements of Angélica S. Gutiérrez and the hardships she overcame to earn them.

Most academics would feel an abiding and justified sense of personal satisfaction in displaying such testimonials. Yet Gutiérrez, 45, who grew up in an immigrant Lincoln Heights family, has to pinch herself frequently in order to believe that her accolades are real.

Like many people of similar backgrounds who she meets through her research, Gutiérrez suffers from the affliction commonly known asimpostor phenomenon, a condition that Gutiérrez refers to as “impostorization.” It’s the uneasy, ever-present sensation that you’re a fraud, your successes aren’t deserved, and it’s only a matter of time before you’re unmasked as the failure you truly are.

Typically, and ironically, it tends to afflict high achievers. In the United States, impostorization also tends disproportionately to affect women, people of color and immigrants or their offspring.

“I do research and I’ve realized that there are quite a few people who feel that,” Gutiérrez said. But, she added, many Latinas and Latinos live the reality of impostorization “when they find themselves in an environment where people don’t look like them.”

The sense of being an impostor often goes hand in hand with the feeling that you must work twice as hard and be twice as successful in order to prove your worthiness in a society that is quick to doubt people like you. The American Psychological Assn. estimates that up to 82% of people in the United States suffer from the condition, which can lead to increased anxiety, depression, less risk-taking in careers and professional burnout.

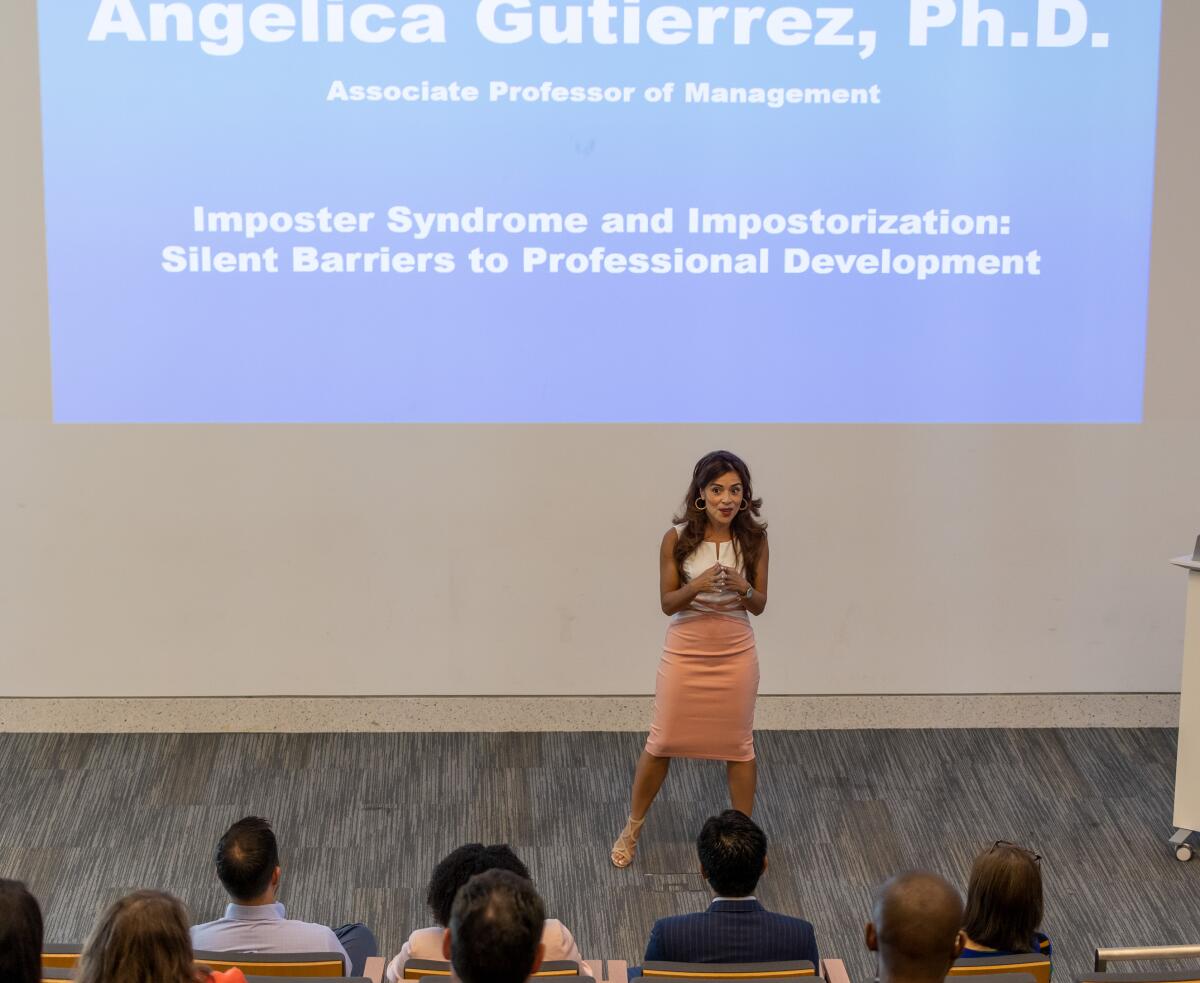

As an associate professor of management at the Jesuit private university on L.A.’s Westside, Gutiérrez helps students of similar backgrounds overcome their own insecurities.

“What has helped me a lot is reflecting on my achievements and remembering that everything I do will help the people who come after me,” she said.

A town in California and another El Salvador look at each other with mixed emotions, a combination of gratitude and guilt.

Among those younger people struggling with self-doubt when she met Gutiérrez was Alyssa Nevárez, a 24-year-old of Mexican heritage from Redwood City. At LMU she earned her bachelor’s in Communications & Chicanx/Latinx Studies in 2021 and a master’s in Business Management degree two years later.

She took Gutiérrez’s class in Management & Organizational Behavior in the fall of 2022.

“Throughout my academic journey at a predominantly white institution, she was the first Latina professor I encountered outside of my Chicanx-Latinx Studies department,” Nevárez recalled.

“The often unspoken norms and culture of the corporate world posed challenges for me, but Professor Gutiérrez’s guidance strengthened my confidence,” she continued. “Professor Gutiérrez understood where my struggles and anxieties came from, because she faced similar challenges when she began her career. When I reached out to her for advice about my future aspirations, she urged me to aim higher, recognizing my potential.”

By most measures, Gutiérrez is academic star. She’s regularly invited to corporate and university conferences on business administration. She frequently gives presentations on “impostorization,” a term she coined from her research and that will be the focus of a forthcoming book.

In 2015, when Gutiérrez was 37, she was selected as one of the planet’s top academics in the field of business administration by Poets & Quants, which annually publishes “The World’s Best 40 Under 40 Business School Professors.”

“Angelica S. Gutiérrez of Loyola Marymount University could be said to be driven by her own drive to overcome obstacles and a genuine desire to help students do the same,” Poets & Quants wrote. Her students say she has “a passion and zeal that is contagious” and that “more than just teaching, she fosters a thirst for knowledge and success in her students.”

Her LMU colleagues likewise hold Gutiérrez in high esteem.

“Her style is very engaging, interactive, and dedicated to ensuring that her students are active learners,” said Dayle M. Smith, professor of leadership and organizational behavior and dean of the LMU College of Business Administration. “Angelica goes the extra mile and she will always be there to support her students.”

Yet in her field, and in her place of employment, Gutiérrez still belongs to a minority. At Loyola Marymount University only 9.8% of professors are Latino or Latina, according to the Institutional Research and Decision Support of LMU. Nationally, 27.8% of business administration academics are Latino, according to The PhD Project.

Gutiérrez has written around 30 academic articles and essays, several of which focus on impostorization. Although the theoretical basis of “imposter phenomenon” derives primarily from psychology and related fields, Gutiérrez focuses on its relationship to corporate practices, social environments and workplace policies aimed at ethnic and other types of “minorities.” Gutiérrez introduced and defined her concept of impostorization in an article published in September 2021 in DiversityIncBestPractices.com.

“I use the term to describe the way in which the environment makes us feel impostors,” she said, adding that she hopes the term will gain traction with other academics and become a preferred term for the condition.

The concept of impostor phenomenon dates to the 1970s when two American psychotherapists, Suzanne Imes and Pauline Rose Clance, defined the phenomenon and began to do research on the subject.

“The phenomenon is very old,” said Elisa Jiménez, psychotherapist and executive director of the nonprofit California Mental Health Connection, noting that it is not yet considered a syndrome because it is not a diagnostic category within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the mental health manual.

Jiménez said that impostor phenomenon is frequently misidentified “as anxiety, depression or low self-esteem, although everything is linked.”

The Santa Ana High School student will study biology in the fall of 2021. But first she had to help her father get out of an immigration detention center.

But the condition goes deeper.

“People with the impostor phenomenon believe that what they are doing is not enough; no matter what they do, they think that they have achieved it by luck,” said Jiménez. People who experience it typically feel ashamed of their successes, and battle “little voices” in their heads telling them they’re unworthy.

“You have to make connections and communicate those fears, find the right people and share those secrets,” Jiménez said.

The pathway that took Gutiérrez to UCLA, where in 2000 she graduated cum laude with a 3.5 GPA and a bachelor’s in political science, then to the University of Michigan and finally to UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, began in Lincoln Heights, where she lived until she was 17.

That was where three primal influences shaped her childhood and adolescence: family, school and her Roman Catholic faith. It also was where some of the lifelong doubts she still harbors first crept into her young consciousness.

Her mother, Imelda Saucedo, emigrated from Durango, Mexico to California in the 1970s. Her father abandoned the family when Gutiérrez was 7, she said. By herself, her mother had to raise Gutiérrez and her younger brother, who were separated in birth by barely a year.

One day not long ago, dressed in jeans and tennis shoes and accompanied by a reporter, Gutiérrez returned to Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, where she attended elementary school. The visit churned up a sea of emotions. Amid the chirping of birds, she talked about receiving the sacraments there, and celebrating her quinceañera. Her family’s home was only about 350 yards from the school, a seven-minute walk.

“It also brings back some sad memories for me,” Gutiérrez said, speaking of her elementary school years. “I remember crying a lot, I suffered a lot because I didn’t understand the [English] language. I wasn’t doing well in class, I was failing subjects, I couldn’t do my homework, so I struggled a lot. I never really thought that I was going to be able to graduate from here.”

José Zelaya, the Disney Television Animation’s only Salvadoran designer and digital animator, as a boy dreamed he would “work for Mickey Mouse.”

Her personal problems weren’t confined to the schoolyard.

At that time, her mother was earning money by splitting time between babysitting, working a few hours for an insurance company and cooking, ironing clothes and cleaning for neighbors. The family’s finances were tight because Gutiérrez’s mother was determined for her two children to attend private school.

Gutiérrez did her part by recycling cans she collected from friends during lunch break. She and her mother foraged for more recyclables in parks on weekends. “I never felt sorry. My mom always instilled in us how important it is to work and get ahead,” she said.

From the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, her family’s neighborhood, up a hill on Galena Street, south of Ernest E. Debs Regional Park, was plagued by gang violence. Police cars and helicopters were omnipresent.

“As soon as the sun went down the shooting began,” she recalled.

Gutiérrez’s mother, who didn’t speak English and had been forced to quit school after sixth grade to go work in a factory, pressed the value of education on her children.

“I want you to study something, so you don’t have to kill yourself as much [working] as I have done,” she’d tell her children upon returning from work with blistered hands.

But before he left the family, the children’s father disagreed that higher education for his daughter would pay off.

“Why are we going to put her in school?” he griped. “She’s just going to get married, she’s going to have children, it’s not worth making any effort, or investing time in her.”

So as not to contradict her husband, Gutiérrez’s mother taught her daughter to read, write and do math at home — but entirely in Spanish. By second grade, the girl’s struggles with English had created a domino effect.

“It is obvious that your daughter has a learning disability, because she does not participate, she does not speak,” the principal and a teacher told Gutiérrez’s mother through a translator. “You are going to have to put her in another school, where they will have special resources for her,” they warned.

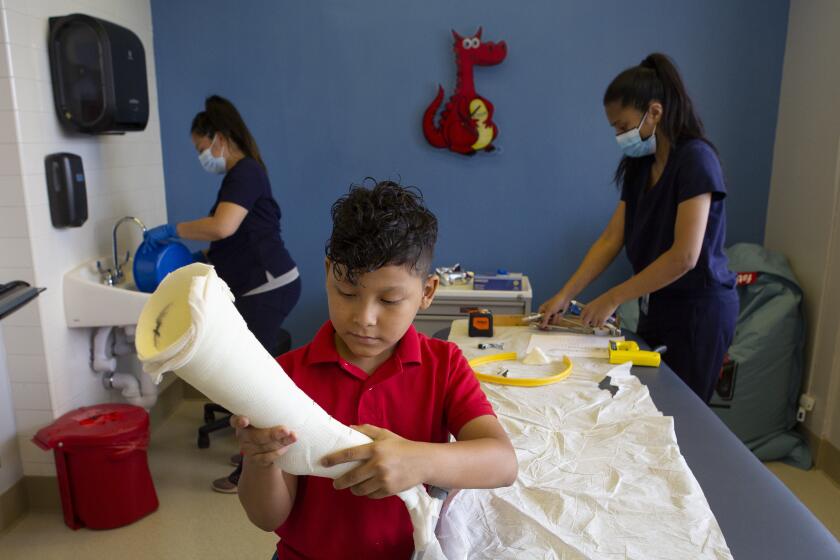

A Mexican boy was born with one leg 11 inches shorter than the other. A remarkable surgery and steadfast friend helped him to walk on his own.

Though she continued to struggle in school for some time, Gutiérrez was able to persevere with the help of two women: her mother, and a high school teacher who constantly encouraged her ambitions and pushed her to join the student council.

During high school, Gutiérrez had been planning to enroll in a community college, take two classes and work full time to help her family financially. But her future turned around when she was awarded a scholarship by TELACU, The East Los Angeles Community Union — a pioneering institution founded in 1968 to serve disadvantaged communities.

“We saw in her a lot of potential, commitment, and a vision not only to help herself, but also others,” said Priscilla Lizárraga, vice president of TELACU. “She is a model, in everything she does she is paving the way for those who come behind.”

Armed with her scholarship, Gutiérrez enrolled at UCLA. In 2007 she became an assistant professor at the university, a position she held until 2012, the year in which she earned her doctorate.

At the time she was hired at Loyola Marymount, the dean was Dennis Draper, a finance professor, who recalled her as the “perfect candidate.”

“We knew that she had a sensitivity to students, we knew that the way she worked with people was challenging and supportive, which is what you really want in a good faculty member,” Draper said.

“She could do all of those things, she could do them effectively, and I knew that immediately in 2013,” he added. “And the last 10 years have proven that to be true.”

In April 2022, Gutiérrez returned to UCLA, her alma mater, at the invitation of the Latino Alumni Assn. Wearing an impeccable purple suit, Gutiérrez, who stands just a fraction over 5 feet tall, made her way to the podium to talk about “the art of the deal.”

“I am super excited to come back home, I spent so many years of my life here,” she told the packed auditorium, launching into her talk with her usual high-energy style.

“I use my hands a lot,” continued Gutiérrez, an accomplished speaker who has given presentations to staff at Mattel, Abbott Laboratories, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Harvard Medical School, among other institutions.

At a prior time in her life, Gutiérrez thought it would be nearly impossible for her to even graduate, let alone become the person giving the lecture.

Her first semester at UCLA, in the fall of 1995, was convoluted and traumatic for Gutiérrez. Although she was only 19 miles from her mother’s home, it was the first time she had lived independently. She felt lonely and sad. There were few other Latino students in her classes.

“It wasn’t difficult academically,” she recalled. The problems were “more emotional and psychological, being away from my loved ones. I felt like a foreigner, like I didn’t belong.”

In more than 40 years of teaching university classes, research professor Concepción Valadez has observed that the environment where students come from greatly influences the development of impostorization. The most alarming effect, she said, is that young people who don’t seek help to set aside those damaging and inaccurate self-perceptions may end up giving up and dropping out.

“It’s not just a problem of the community itself, but it’s a problem of the country,” said the UCLA Department of Education researcher.

Valadez said that many Latino students arrive at university thinking that they are not prepared. They are afraid of failing, and feel they don’t belong in their new environment, where often they are in a minority. They get frustrated when they don’t obtain the same good grades they did in high school.

It’s important for such students to realize that what they may view as a permanent setback is likely only a temporary challenge.

“It is not forever,” Valadez said. “Don’t accept that it’s a label for life, don’t let others put that mark on you that ‘you can’t.’”

That’s the message that Gutiérrez now delivers in her own classroom and by visiting schools and community centers.

“I try to go give presentations and tell them a little more, because it makes a big difference to see a Latino or a Latina,” Gutiérrez said. “It’s important to motivate students and make them feel like they can succeed.”

Darnell Brown, 23, a native Angeleno who graduated from LMU in May with a master’s degree in management and now works for a telecommunications company, said Gutiérrez helped him overcome his own feelings of impostor syndome.

“It definitely hits a bit at first, especially when you start to settle into these high positions and realize that there are less people who look like you or wear your skin color,” said Brown, who is African American.

Brown said Gutiérrez continues to offer him support in his new career as a sales and marketing coordinator.

“I’ve realized learning to conquer these feelings is part of the road to strengthening your confidence as a person and that you will always be your worst critic,” he continued. “The second you realize you truly deserve to be where you are at, all the hard work you’ve put in, and everything your family/friends may have sacrificed to get you where you are, I believe you’ve already taken the first steps to overcoming it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.