A California city that became Little El Salvador feels the pain of separation from its parent

SENSUNTEPEQUE, El Salvador — The people who stayed behind in this Salvadoran hill town, and those who fled to California’s San Joaquin Valley, think of each other with mixed emotions.

Love and pain. Longing and envy. Gratitude and guilt.

Separated by 2,500 miles, Sensuntepeque, in central El Salvador, and the dusty farming community of Mendota, 35 miles west of Fresno, are joined as if by an umbilical cord of financial need and emotional codependency.

Over the last three decades, Sensuntepeque, population 40,000, has sent migrants — thousands of them — to the United States. The San Joaquin Valley has become home to so many Salvadorans that the government of El Salvador opened a new consulate in Fresno this month, adding to those already in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Most Salvadoran exiles were desperate to escape endemic poverty, failing farms and the lingering torments of a long-ago civil war. But the mass outflow left many broken households in its wake.

“That they are so far away, without being able to see them, it is a nightmare, and the family is not complete,” said María Hilda Carballo, 53, whose two daughters left for the Central Valley years ago.

In California’s farm belt, communities such as Mendota, population 11,500, have come to rely on the sweat and muscle of Mexican and, increasingly, Central American migrants to extract profit from the land.

“This is a mini El Salvador,” said Miguel Urías, a native of El Salvador and co-owner of Antojitos Guanacos, a restaurant and bakery chain, and one of many Mendota businesses whose names signal their Salvadoran roots. “From six years ago to now, I see that we are arriving in droves.”

In return for the low-wage labor it receives, Mendota sends thousands of dollars in remittances back to Sensuntepeque and the surrounding departamento, or state, of Cabañas.

A UCLA grad whose college career overlapped with her mother’s researched the joint journey of mothers and daughters pursuing higher education.

In 2020, despite the pandemic, El Salvador raked in almost $6 billion in remittances from the United States, an increase from 2019 of 4.8%, according to the country’s Central Reserve Bank. Cabañas in 2020 received a monthly average of $357 per household, second highest among the nation’s 14 states.

“The economy, without remittances, would not move,” said Edgar Bonilla, who was mayor of Sensuntepeque from 2006 to 2021. According to Bonilla, 75% of Sensuntepeque’s population has relatives in the United States, and at least half of those receive remittances from a California town many never will visit.

Money wired from California has launched businesses, bought homes and filled them up with consumer goods.

“They send remittances to these people every day, the banks are full every day,” says Rosa Barrera, 46, who sells fruit, juices and snacks.

In many ways, the relationship between these kinfolk communities is mutually beneficial and harmonious. But there are strains.

Dollars dispatched from California have turned this corner of El Salvador into a commercial hub — it now boasts 10 banks and financial cooperatives — but also made housing costs soar. Inequities are more visible than in times past.

While more homes in Sensuntepeque now sport flat-screen TVs and late-model cars in their driveways, the region’s roads remain cracked, its schools underfunded, its medical clinics lacking in supplies.

The disruptions go deeper. In the downtown area of Sensuntepeque, whose Indigenous name means “400 hills,” some houses now cost up to $300,000, while a lot of about 2,700 square feet goes for $10,000, said Paul Nimrod Salgado, a real estate agent. Those are princely sums in a nation where the yearly per capita income is $4,000.

And while remittances soar in Sensuntepeque, in Mendota residents face a housing shortage.

“It is very difficult because there are no homes available,” said Sindy Orellana, 19, a Salvadoran immigrant who is looking for a house for her family and currently pays $1,000 to rent a two-bedroom apartment.

The farmworkers and restaurant owners of Mendota take pride in being able to subsidize their far-flung relatives. But some also feel the nagging burden of expectation, of having to work long hours while trying to master a new language.

“To feel stable, you have to pay a very high price,” said Emérita Barrera, who immigrated to the United States in 1994.

::

The 12-year armed conflict between the U.S.-backed, right-wing Salvadoran government and leftist guerrillas supported by Cuba claimed 75,000 lives in a country of only 4.5 million people at that time.

Remittances sent from Mendota have helped the Sensuntepeque area not only recover but attain a lifestyle unimaginable before the war.

In the hamlet of San Pedro, rising out of a scrim of cornfields and dirt streets, old mud huts give way to showy concrete block houses. A sudden blast from a truck’s loudspeaker breaks the subdued atmosphere.

“We have potatoes, cabbages and carrots!” a rough male voice intones. The same vehicle is hawking chairs, mats, plastic jugs and other consumer goods.

“The inhabitants here have the best telephones and televisions,” says Miguel Amaya, 25, a Sensuntepeque resident who works as a driver, watching the street scene unfold. “Do you think these houses are going to be owned by poor people?”

Down a slope, a few paces past a Catholic church, sits a two-story, four-room home with fine wood finishes and gilded columns. Its owner is María Hilda Carballo. One of her daughters, Maria Cindy, 29, immigrated to Mendota, and another, Griselda, 35, to nearby Kerman. They’ve not been able to see their mother since they left home many years ago.

Today, the sisters labor in tomato and almond orchards to scrape together about $200 each month to send Carballo.

Sylvia Mendez well remembers being sent to a “Mexican school” in Orange County. Her parents’ landmark lawsuit challenged segregated schools in California.

“They both help me with what little they make there,” she said.

Carballo’s spacious house was paid for by her brother Julio, who also moved to Mendota. She lives with another daughter and two teenage granddaughters. Previously, she lived in a house made of mud and pieces of wood while raising corn and making cheese to survive.

In the same hamlet, across a stream and up another steep slope, María Gloria Reyes, 49, lives with her husband, five children and a grandson in the $40,000 home paid for with help from her sons, Emanuel, 27, and José, 32, who joined the exodus to Mendota in the early 2010s.

“Seeing the poverty here, they decided to go there,” Reyes said as she tossed tortillas on a griddle.

In the uncertain weeks while her sons made the dangerous trek, Reyes felt despair and a pain in her chest, wondering whether she’d ever see them again.

“You don’t know what can happen on the roads,” she said.

Before their new house was built, Reyes and her husband, Leandro Membreño, rented a hovel made of clay and galvanized metal sheets. These days, Membreño has the luxury of spending more time relaxing in his hammock, but everywhere are reminders of a family apart.

“When you make a meal, you remember them,” Reyes said. The brothers’ favorite dish is the memory of their mother’s chicken soup.

::

I had the dream of doing something different. Many people come risking their lives. We Salvadorans are very strong at climbing our way to get ahead.

— Emérita Barrera

Dogs bark on a dark, cold morning in Mendota. The clock says 5:30 a.m., but the parking lot of Sonora Market already has become an anthill as trucks cruise in and out disgorging farmworkers. They dash into the store and quickly emerge clutching coffee cups and sweet bread.

It’s the daily routine in a community whose residents help stock the refrigerators and fill dining-room tables across America.

Abdul Obaid, a businessman from Yemen, said that the town’s demographic map has completely changed in the 17 years since his family established the Sonora Market and its nearby sibling, the Mendota Valley Food supermarket, both liberally stocked with popular Salvadoran fare.

“The Salvadoran population has quadrupled in a decade, and it is because people go where they feel at home,” Obaid added.

Originally developed in 1891 as a storage site for the Southern Pacific Railroad, Mendota was incorporated in 1942, and its prosperity hinges on the production of almonds, pistachios, melons, tomatoes and corn. In 2019 the county’s farmworkers yielded $1.5 billion in almonds, $962 million in grapes and $660 million in pistachios.

When María Hilda Carballo’s brother, Julio Carballo, left El Salvador in 1994, he was 14 years old. Knowing that he could get work in Mendota harvesting melons and asparagus, he decided to go live with an uncle there.

It’s exhausting work, said Carballo, 42. “You have to go to work very early,” he said. “The cold is very heavy.”

He spent about five years in the fields before he got a business license and became a truck driver. In 2004 he took out a loan of $40,000 to buy his own vehicle and started his company, JCC Transport Inc. Today he owns 25 trucks and is in charge of more than 40 employees.

Now that his entrepreneurial drive has paid off, and his immigration status is covered by the federal Temporary Protected Status program, he said, “I can retire tomorrow.”

Luis Fernando Macías, professor of migration studies at Fresno State, said that the work formerly done by Mexicans in Mendota is now mostly performed by Salvadorans. In the early years of Salvadoran migration, that sometimes gave rise to tensions.

“When I came, it was a bit complicated. The Mexican people looked down on you. There was always discrimination when you went to work,” said Tulio Vargas, 52, a Sensuntepeque native who arrived in Mendota in 1980.

Waves of Salvadoran immigrants have enlivened Mendota’s taste buds, serving pupusas, torrejas, mata niños bread and garrobo soup, named for its main ingredient, an endangered black spiny-tailed iguana.

“Now, it is a community only of Sensuntepeque, purely the department of Cabañas,” said Carmen Chévez, 69, who left El Salvador in the 1990s.

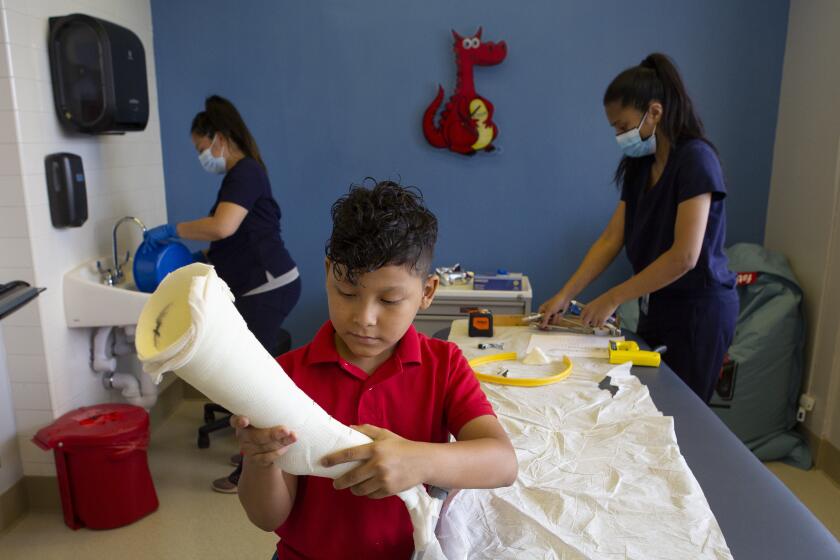

A Mexican boy was born with one leg 11 inches shorter than the other. A remarkable surgery and steadfast friend helped him to walk on his own.

Emérita Barrera arrived in Mendota thanks to a permanent residence request made by her husband. Though she’d studied cosmetology, she, too, started out in her adopted country working in the tomato fields.

After 10 years, she took a hiatus to obtain her GED, became a naturalized citizen, took classes at a Fresno beauty school along with some business administration courses, and eventually opened her own salon.

“I had the dream of doing something different,” she said. “Many people come risking their lives. We Salvadorans are very strong at climbing our way to get ahead.”

The trauma of leaving behind her parents and six siblings still haunts her. Her parents died in 2013, while Barrera was outside her native country. She last visited El Salvador in 2018.

Despite carving out better lives economically, Mendota’s Salvadorans face enormous challenges.

According to the Census Bureau, 40.9% of Mendota’s population lives in poverty. In 2019 the average income per household was $31,237. An estimated 40% to 60% of the population is undocumented.

In the 2015-19 period, the high school graduation rate was 30.8%, and only 1.5% of Mendota’s population obtained a bachelor’s or other college graduate degree.

These statistics do not reflect the story of Jessenia Núñez, who will soon be able to display her law degree.

The daughter of migrant farmworkers from Sensuntepeque, Núñez was born in 1992 in Riverside County. When she was in second grade, her family settled in Mendota and pushed her to go to college — first UC San Diego, where she earned a political science degree, then UC Berkeley School of Law.

“I owe a lot to Mendota, to my parents, to my entire family who have always supported me,” she said. “I watched my parents struggle. They taught me to persevere.”

::

Across the miles, the California farm town and the Salvadoran hill town still dream of each other. Tulio Vargas, still remembers the day he left Sensuntepeque, as an 8-year-old with his mother and two brothers.

“We went out at dawn,” he recalled. “We didn’t want to tell anyone.”

The Salvadoran military government and its ruthless state security apparatus were “disappearing” and killing anyone they suspected of sympathizing with the rebellion. Vargas said security forces were involved in killing his father and a fellow businessman. Fearing reprisals, the family fled.

“We practically left the house abandoned,” he said.

The family initially settled in Belize, but two years later, at age 10, Vargas and a friend moved on to Mendota. Over the decades, he rose to become a farm administrator and, like so many others, sent remittances to his homeland.

Back in the Los Remedios neighborhood of Sensuntepeque, an uncle has managed to hold on to the house where Vargas and his family once lived. Vargas now visits his hometown once or twice every year, though Mendota is home too.

“The truth,” he said, “is that El Salvador is one’s land, whatever it may be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.