Veterans’ claims over misuse of the VA West L.A. campus may go to trial

A federal judge has set the stage for a possible trial next year in a lawsuit challenging leases of land on West L.A.’s Veterans Affairs’ campus to UCLA and a private school and the slow progress of the VA’s promise to build housing for homeless veterans.

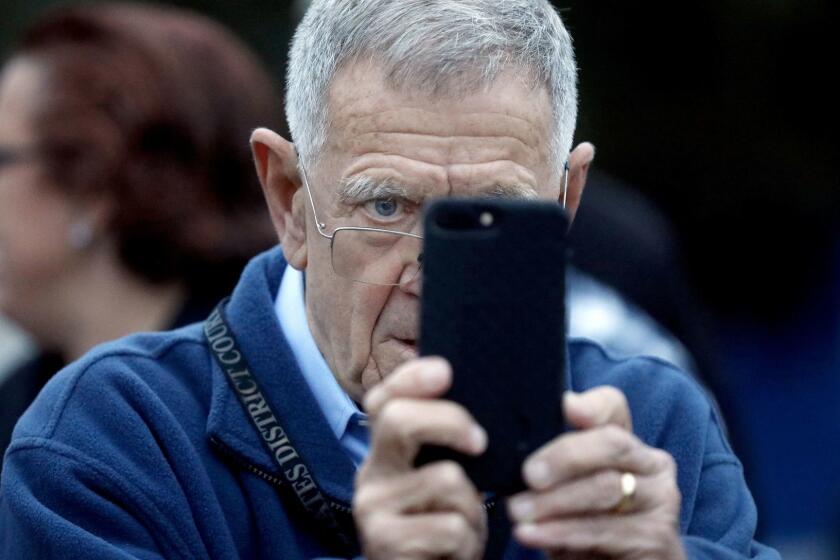

In a tentative ruling he warned he may change, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter denied motions to dismiss key portions of the class-action lawsuit that seeks to declare the leases illegal and compel the VA to expeditiously provide housing for thousands of homeless veterans.

Carter handed out the pre-written tentative ruling following a 3½-hour hearing Monday in which, he said, arguments by lawyers representing the veterans and the VA had caused him to “rethink the entire jurisprudence.”

Without indicating which way he might have been swayed, Carter gave the parties until Sept. 29 to respond to the tentative ruling before he makes it final.

In a quip characteristic of the mercurial judge, Carter warned reporters after the hearing to be wary of describing the ruling with a finality that could turn out wrong.

The split decision, if finalized, would dismiss several elements of the case based on jurisdiction but maintain two main allegations.

The defendant, facing prison for violating his probation, stood in a federal courtroom asking for another chance.

Carter wrote that he was inclined to uphold the veterans’ contention the VA has a fiduciary duty to “evaluate management of leases or land use to ensure that they advance the purpose of providing housing and services that principally benefit veterans and their families.”

He would allow the veterans to go forward with their cause of action alleging that leases to the Brentwood school and a company that operates a public parking lot breach that duty, which is laid out in the West Los Angeles Leasing Act of 2016.

Carter dismissed other claims that several easements over the property for utilities and transportation violate the leasing act.

If adopted, the ruling could lead to a trial over whether to invalidate leases under which UCLA and the Brentwood Academy have built extensive athletic facilities on the VA land.

Zachary Avallone, trial attorney for the U.S. Justice Department, argued during the hearing that the leases were serving veterans by providing exclusive access to facilities at specified times.

Carter’s tentative ruling rejected that argument.

“Under a common-sense reading of the statute, leases for a private school’s athletic facilities and a parking lot for the general public are not designed to ‘principally benefit veterans and their families,’ even if veterans marginally benefit from these agreements,” he wrote.

Carter wrote that the federal government was originally granted the land in 1888 with the stipulation it “locate, establish, construct, and permanently maintain” a branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, which constituted a charitable trust to provide housing for the disabled veterans.

When Congress passed the West Los Angeles Leasing Act of 2016, he wrote, it assumed the government’s duty to enforce that trust.

Carter urged the parties to work out an agreement to avoid a trial, but said he would schedule one for early next year if they do not.

The lawsuit reprises an earlier one that ended with a 2015 agreement by the VA to build 1,200 units of housing on the campus with a commitment to complete more than 770 by the end of 2022. Only 54 of those units were completed by then, and to date 233 are available.

Avallone told the court that the agreement contained no timeline and that the 1,200-unit goal came from the 2016 Master Plan prepared pursuant to the agreement.

The failure to include mechanisms to enforce that agreement was an error, said Mark Rosenbaum, an attorney with the pro bono law firm Public Counsel, one of four firms that represented veterans in the earlier case.

The new lawsuit, filed in November, asks the court to appoint a monitor to enforce any orders. It goes even further in its demands, asking for an order requiring the VA to provide 3,700 units of housing leased off campus.

Rosenbaum argued that the goals in the earlier agreement were insufficient because there are currently nearly 4,000 homeless veterans in the county.

The new lawsuit added the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA) as defendants, alleging that procedures for processing housing vouchers for veterans inhibit veterans’ access to permanent housing. The lawsuit said only 60% of the 9,800 veterans’ vouchers allotted to Greater Los Angeles are in use.

In particular, disabled veterans are excluded access to housing subsidies, they argued, when their disability payments exceed the income limits set by the government.

“The more disabled these veterans are and the more they require accessible VA services by the VA’s own assessment, the less they are able to meaningfully access them.”

It was unclear whether that claim would go to trial under Carter’s tentative ruling which did not address the allegations against HUD and HACLA.

Several times during the hearing, Carter interjected his own deep concern over the plight of all homeless veterans including those living far from the VA on Skid Row.

“How do we get the big picture?” he asked at one point. “We want to be looking at who these people are — a huge number of people without limbs and with traumatic brain injuries.”

At another point he pressed Avallone for details on how much outreach the VA does in other parts of the county.

In an unusual courtroom scene, Carter instructed Avallone to call a temporary housing hotline number on a VA billboard in Skid Row.

On speakerphone to the court, the woman who answered described VA outreach there and in other parts of the city but could not allay Carter’s skepticism with any specific details.

“I am out there a lot,” he said. “I haven’t seen it.”

Reacting to plaintiff’s attorney Roman Silberfeld’s contention that the VA “went astray” in the 1960s and 1970s by eliminating housing for 4,000 disabled veterans, he exclaimed, “What the heck happened? How is it we had 4,000, and in 2023 we have 233?

In an earlier hearing, Carter had disclosed several potential conflicts including that he was a Marine veteran and a UCLA graduate, but would not disqualify himself.

While leaving his final decision open, Carter ended the proceeding with a strong warning that a new settlement would require an enforcement mechanism.

“I’m not signing off with anything that doesn’t have accountability,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.