The 1971 Sylmar quake is keeping veterans homeless in L.A. in 2020. That may change soon

When Del Gill arrived at the sprawling West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus in 2016, federal officials had just unveiled a master plan for transforming dozens of disused historic buildings into permanent housing for veterans like him.

Four years later, the ex-Marine still lives in a tent.

“I don’t see any ground being lifted or bricks getting stacked,” Gill said, nodding over the fence from San Vicente Boulevard, where he and other homeless veterans bed down every night. “All these old buildings ... they just let them sit vacant.”

That may soon change. This summer, developers plan to gut Building 207, a midcentury Mission Revival-style ward of weathered stucco and terra cotta tile, transforming the former hospital into 59 units of permanent housing for homeless veterans that will one day anchor an enclave of 1,800.

Yet few Angelenos remember, less than 50 years ago, 2,800 veterans lived on the campus. The land was used primarily as housing from 1888 until 1972, when the federal government evacuated residents and shuttered what was then the largest veterans housing development in the country.

If Building 207 is finished on schedule, it will end half a century of decay set off by the 10-second Sylmar earthquake.

“We all own this land, it’s all dedicated [to] veterans,” Mayor Eric Garcetti said of the campus, where officials have tried and failed to rebuild housing ever since. “People are encamped all around this property, and then there’s all these acres inside — if we can’t solve it here we won’t be able to solve it anywhere.”

The multimillion-dollar rehabilitation of Building 207 will be a test case for the West LA Veterans Collective, a partnership between the veterans-services nonprofit U.S. Vets, Century Housing and the developer Thomas Safran & Associates, which contracted to produce the bulk of the community mandated by the plan.

Proposed names like Arroyo Pacific and Vetwood Village and Stearns Baker Park nod to the site’s storied past. But its more recent history — the story of how Building 207 and so many others came to be vacant — is quietly left out.

“We decided early on that we were going to start from today and go forward,” said U.S. Vets Chief Executive Stephen Peck. “We know we know how to do this, that we can create a cohesive campus. We’re creating a real community.”

The community was a hard-won victory for homeless veterans, who sued the VA in 2011 over mismanagement of the land.

But the sudden mass eviction, more than any other policy or event, is what seeded the rot on the campus. It set the stage for the controversial leases and decades of neglect at the heart of the 2011 suit. The removal, its aftermath and the seismic events that led up to it continue to shape the lives of the nearly 4,000 homeless veterans living in Los Angeles today.

::

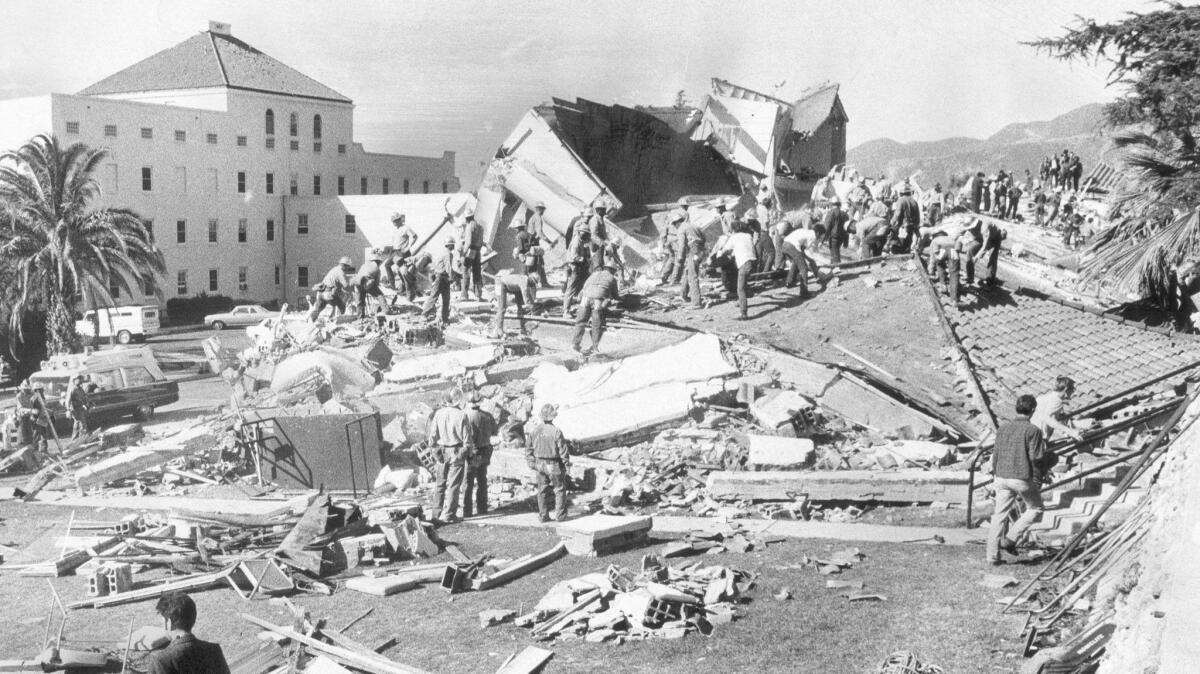

The West L.A. VA’s housing crisis began 42 seconds after 6 a.m. on Feb. 9, 1971, when a 6.5 temblor jolted the slumbering foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains.

The Sylmar earthquake killed 58 people. Forty-nine of them died at the Sylmar VA. Witnesses later told members of the House Committee on Veterans Affairs that two hospital buildings collapsed “in a cloud of dust” while the ground was still shaking.

The Times is launching a new section on latimes.com to bring together our best coverage to date on both homelessness and housing.

“Just collapsed instantaneously?” Rep. Roman Pucinski (D-Ill.) asked, according to congressional transcripts.

“Instantaneously,” San Fernando engineering officer Clifford Lemear said.

“There was no forewarning?”

“None whatsoever,” Lemear said.

Members of the committee summoned UC Berkeley professor Bruce Bolt and other eminent seismic experts to testify at a special hearing convened in Los Angeles nine days after the earthquake. Lawmakers wanted to know how the disaster had happened, and how many more of their buildings might be at risk.

Records show federal officials were initially optimistic about California VA facilities, including the L.A.-area hospitals where survivors were evacuated. The buildings that collapsed in Sylmar had been erected in 1925 — eight years before early seismic engineering codes were introduced across the state — while many others had more modern infrastructure.

But VA engineers had assessed the failed buildings just three months before the earthquake, and declared them to be safe.

Help us inform our reporting about the homelessness crisis in California by submitting your questions.

The ultra-modern Olive View Hospital, located not far from the Sylmar VA, had also suffered significant damage despite being built to the most recent codes. Congress was adamant that the VA take every precaution to avoid future seismic failures, no matter the cost.

“We have to make a tough decision. We either have to abandon those facilities, build new ones, or spend the [money] to restructure them,” Pucinski told the L.A. subcommittee hearing. “We have a lot of hospitals and a lot of veterans and staff who, in the wake of this tragedy, must be protected.... Any way you look, it’s going to cost money.”

Earthquake engineering was “still an art, not yet a science,” expert Henry Degenkolb told the panel. Studies should be conducted with all possible speed, but it was ultimately impossible to know the extent of the vulnerabilities, or how costly they might be to fix.

Congress appropriated millions for the seismic studies, which were completed by private contractors in the months that followed. But the results were not made public.

Instead, records show that on the morning of Jan. 14, 1972, top VA officials converged on the West L.A. campus, where Deputy Administrator Fred Rhodes declared 30 of its 236 buildings uninhabitable, and ordered 1,460 residents evacuated by the end of February.

The homes were not themselves unsafe. But the VA had decided to convert them into medical wards while a new “earthquake proof” hospital was built.

“This has been a very traumatic situation for all of us,” J.J. Cox, the VA’s Southern California Regional Medical District director, told The Times in 1972. “Had we been able to extend the time limit, we would have done it, but we had to make the moves as rapidly as possible.”

At the time, residents were mostly elderly — a man interviewed in 1970 said he’d fought in the Spanish-American War — but a growing number were in their teens and early 20s. Reports indicate that by the time the housing units were evacuated, they were already home to hundreds of Vietnam veterans.

Inside a decade, such men would be L.A.’s largest homeless demographic.

Records show the VA spent more than $8 million transforming former housing into medical facilities like Building 207, the first of which opened that May. All other repairs were deemed “not economically feasible” by the federal government. That decision was reaffirmed a year later, during an appropriations hearing in 1973.

“What this committee wants is specific assurance that if we are going to spend money out of this VA budget that it is not going to be jeopardized,” said Rep. Joseph McDade (R-Pa.). “You have already had to close a series of existing buildings. We don’t want to put additional money in and find out that it is going to be good money after bad.”

The first disputed leases followed within weeks.

::

In May 1973, the L.A. City Council opened discussions to annex portions of the campus they expected the federal government to declare excess. Reports from the time show the Brentwood School was already courting its controversial lease.

That same year, UCLA received a donation for its Jackie Robinson Stadium. A plot in Westwood was tentatively selected, but when homeowners pushed back in 1976, the university turned to “surplus” land on the VA campus instead.

The $83.7-million Wadsworth Hospital opened in March 1977, making the hastily converted medical wards redundant just five years after veterans were evicted. The same buildings that had housed “old soldiers” for decades were leased off or abandoned while hundreds of young ones slept on the street.

The decade that followed saw L.A. overwhelmed by homelessness. Official estimates from the mid-1980s put L.A.’s unhoused population at 30,000 to 50,000 -- though such estimates are considered far less reliable than those made today. At the time, a third were believed to be veterans.

On the Westside, that percentage was closer to half. In Venice alone, UCLA researchers estimated that 33% of the homeless population had served in Vietnam.

Still, plans to restore housing on the vast VA campus foundered.

“We knew that wherever there were homeless, there are going to be veterans,” VA social worker Margaret Ronan told The Times in 1988. Yet, months earlier, neighbors had scuttled a city plan to house veterans in city-owned trailers on the site, which had fewer than 300 shelter beds. U.S. Sen. Alan Cranston wrote to demand a survey of vacant buildings that might be converted to housing, but little was done.

Instead, by the early ’90s, huge encampments of homeless veterans emerged on the edge of the land. Veterans like Gill still live there today.

Outside experts were cautiously optimistic the new West L.A. development could at last reverse that trend.

“Affordable housing is a huge deal and there’s not a lot of it, particularly for veterans,” said Kathryn Monet, chief executive officer of the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans. “We’re pleased to see that the VA is starting to prioritize that.”

Still, there are no current estimates of what the community will cost, or who will ultimately pay for it.

“With a recently approved campus plan, we are currently working to assess full scope of infrastructure, historic preservation, and other costs across the campus — and also the ways that we can partner with VA, government and our community to achieve this vision,” said Peck, the U.S. Vets CEO.

But history weighed heavily on the San Vicente Boulevard encampment.

“Wasn’t this land given to veterans?” asked Gill, the ex-Marine. “I’d love to see them give us back the VA.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.