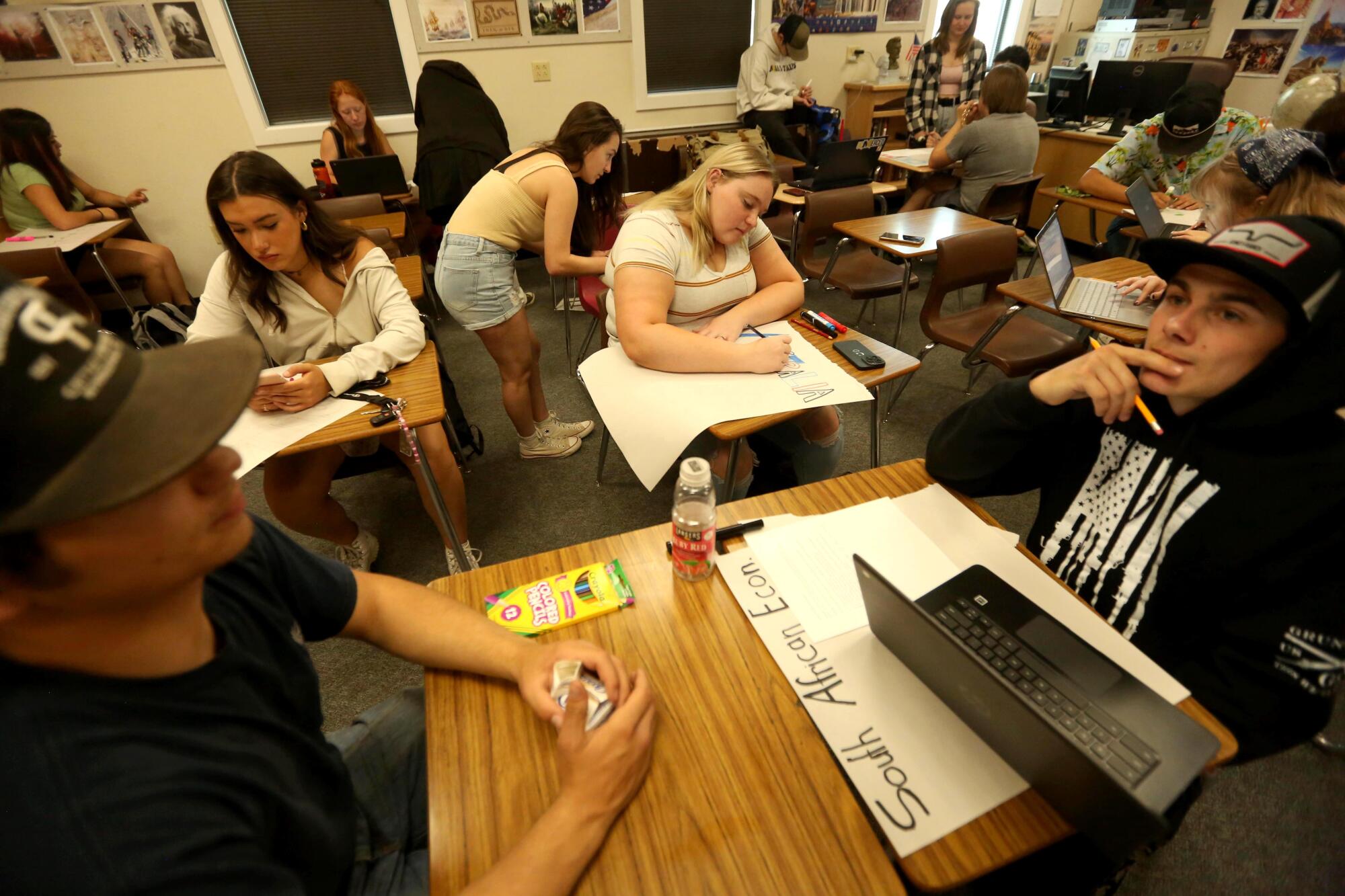

ALTURAS, Calif. — Linda Plumlee struggled to look alert in her economics class.

Her teacher was asking whether the students had heard about the recent closure of Silicon Valley Bank. (They had. On TikTok.)

Plumlee, a bubbly cheer team captain and student body president at Modoc High School, sipped an iced oat milk caramel macchiato. She was exhausted. And she had to go straight to work — at one of her two jobs — after class that snowy spring day.

She was waiting for college acceptance letters. She had a speech competition to prepare for. Homework to catch up on. Scholarship essays to write. And yet another room to finish moving into.

For more than two years, Plumlee, 18, had essentially been homeless.

She’d bounced around this rural Northern California town, sleeping on couches and spare beds and, for a stretch, the back seat of her car — all while organizing blood drives and getting good grades and helping classmates with their homework.

In this occasional series, we explore rural, conservative California through its struggling schools, which are cornerstones of life in small towns.

Like Plumlee, even the most ambitious students in California’s impoverished rural north often deal with extreme challenges, including poverty and neglect, at higher rates than anywhere else in the state.

For Plumlee, academics were a ticket out of Alturas, a cattle-ranching town of 2,700.

“I want a future,” she said. “I want to do something with my life. And I’m the only one who’s going to get me there.”

Plumlee is so responsible that other kids called her mom. Most people didn’t know what she was going through outside of school.

About eight years ago, educators in Modoc County realized they had a serious problem.

Students kept melting down, becoming so angry or disruptive that they had to be pulled from classrooms. The county’s suspension rate was about three times higher than the state average, and students were twice as likely as those statewide to be chronically absent.

“We realized we were dealing with something bigger than behavior,” said Misti Norby, deputy superintendent of the Modoc County Office of Education. “We were like, what’s going on with our kids?”

A rural California school district scrambles to find teachers amid a national shortage. It will not offer transitional kindergarten, despite a new law.

Teachers across Modoc County assessed their students, relying on a fact of small-town life that can be both a blessing and a curse: everyone knows everyone’s business. They did an informal, anonymous tally of what are called adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, which include abuse or neglect; a parent’s death, incarceration or divorce; and mental illness or substance abuse in the home.

About 58% of kids in Modoc County, Norby said, were believed to have four or more ACEs, putting them at significantly higher risk later in life of suicide, substance abuse, chronic health problems and unemployment.

“It was very eye opening,” Norby said. “We now function on: We know they have trauma. Somewhere. Somehow.”

Models consistently show the state’s highest rates of childhood trauma are in rural Northern California, where there is a dire shortage of both primary care and mental-health care providers.

The gun violence and poverty experienced by young people in some urban neighborhoods is well-documented in the media and popular culture. But these issues are as present, if not even more common, in rural areas. While homicide rates are lower, suicide rates are generally much higher in rural than urban counties.

Home to just 8,500 people, Modoc County is one of California’s poorest, with a fifth of the population living in poverty.

People are drawn to the region’s rugged natural beauty, seclusion and cheap housing. But in Alturas, the county seat, many storefronts along Main Street have long been boarded up. The last major sawmills closed three decades ago.

The flip side of seclusion is isolation, which begets boredom, depression and addiction.

Now, when social workers or other county officials learn that a child has experienced a major trauma, they email Norby, who then emails the child’s school district.

She provides no details about the incident. Just a name and the words: “Handle with care.”

One day in early March, Plumlee left campus on a lunch break. Her belongings — clothes, succulent plants, boxes of Cheez-Its — rattled around the back of her 1999 Infinity SUV, which topped out at 65 mph on the highway and was nicknamed the Mom-Mobile by classmates. She was driving to her newest home to check on her dog, a 14-year-old long-haired chihuahua named Boo who had cataracts and seizures.

Plumlee and Boo were sharing a Disney-themed room with a 5-year-old girl. A quote from “Lilo & Stitch” was painted on the wall: “‘Ohana’ means family. Family means nobody gets left behind or forgotten.”

A California lumber town has repeatedly bounced back from adversity —fires, economic downturns, COVID-19. Like the town, Chase Kirby is a survivor.

Growing up, Plumlee didn’t have much of one herself.

She was born in Tulsa, Okla., and her father died when she was young. Her mother, she said, won’t discuss his death. She doesn’t know any details.

When she was 5, Plumlee and her mother moved to Alturas — she doesn’t know what drew them to the town. They stayed in hotels and with friends and her mother’s boyfriends, she said. For a few years, they lived with an older couple, whom Plumlee called her grandparents.

In eighth grade, Plumlee said, she was pulled out of class and home-schooled. But, she added, she was mostly helping take care of her “grandpa,” who was dying of prostate cancer, and doing work around the house.

After his death, mother and daughter took off.

Plumlee convinced her mom to move into a low-income apartment. She said she filled out the application, but her mom — the adult — had to sign it.

She says her mom would be gone for weeks at a time.

In a Facebook message, Helen Plumlee disagreed with her daughter’s account. “We didn’t fight ... I never left her for weeks at a time,” she wrote.

Linda Plumlee’s story was confirmed by school administrators, her high school counselor and two former bosses.

In the apartment, Boo, who weighed all of 9 pounds, usually was Plumlee’s only company, she said. The dog couldn’t fend off an attacker, Plumlee knew, but she could at least bark if someone tried to break in. (Boo died last week.)

Plumlee — who has long, honey-colored hair, wears horn-rimmed glasses and skinny jeans and adores Taylor Swift — bought her own groceries. She cooked her own meals.

At 14, she worked as a ranch hand. She cleaned hotel rooms and watched people’s dogs and bagged groceries at the Holiday Market. She helped her mom pay the bills.

Her grades plummeted.

Often, the struggles of small-town youth are overlooked by policymakers and college recruiters in this “very metro-centric state,” said Lisa Pruitt, a professor at the UC Davis School of Law whose research focuses on rural places and who has taught small-town youth emancipated by a court from their parents’ custody.

Pruitt said a big challenge is the lack of anonymity.

Having everyone know your business can be a double-edged sword, she said, when “the whole community is watching these sort of ongoing train wrecks that families are experiencing.”

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, behavioral issues and suicidal ideations among students have skyrocketed in Modoc County, as in many other places.

Tom O’Malley, superintendent of Modoc Joint Unified School District, said he is also seeing more students who suffer neglect and abuse at home.

There was the third-grader who got a younger sibling dressed, fed and walked to school each day. Kids who show up to class exhausted after being up all night while their parents partied.

“There are kids who come in and we get them food and we take them to a different room and let them sleep for a while,” O’Malley said. “You can’t learn if you’re physically exhausted or mentally exhausted or starving.”

Outside of her close relationships with educators at school, Plumlee mostly kept her troubles private, even from friends, and tried to rely only on herself.

She was a freshman in March 2020 when the pandemic shut down everything.

For a teenager accustomed to chaos, the quiet boredom of an empty apartment was maddening. She completed her two-week homework packets in a day. She deep-cleaned and rearranged the furniture, over and over. She watched 15 seasons of “Criminal Minds.”

She fought anxiety. She was embarrassed to pick up free to-go meals from school by herself, while other students came with their families.

“It was so hard,” she said. “School’s a regularity. Like, the one thing that I have. Somewhere to go. And food. I get breakfast and lunch there, and I don’t have to worry about it.”

In a vast, rural Northern California county with few cases of COVID-19, a public school district reopened to in-classroom instruction, even as most in the state are doing virtual distance learning.

Schools across sparsely populated rural places such as Modoc County reopened their classrooms that fall, much sooner than in urban areas.

During her sophomore year, Plumlee was trying to keep her head above water: Getting her grades up. Working multiple jobs.

She kept her wages in cash in a lockbox under her bed because she was too young to open her own banking account.

Finally, she went to the copper-domed Modoc County Courthouse. She needed control of her own money, to make her own medical decisions and to have full control over applying for college and financial aid.

After proving to a judge that she was living independently and managing her own finances, she became legally emancipated from her mother.

Then, Plumlee said, her mother — whose name was on the lease — kicked her out of the apartment.

Helen Plumlee denied pushing her daughter out. “The emancipation was her idea and I agreed with it because I figured it was best for her to get ready for college,” Helen Plumlee said in a Facebook message. “She did help pay the bills and we split the food stamps.”

Eventually, Linda started couch-surfing. She slept, for a while, in the back of the Infinity, curled up next to Boo.

Plumlee said that what got her up every morning was her life’s goal: going to a four-year university. And getting out of Alturas, which held too many tough memories.

But leaving would be bittersweet.

Alturas was where she and her friends cruised Main Street, cracking jokes and dreaming about the future. It was where teachers and school counselors spent countless hours keeping her spirits up through the emancipation process.

Most stores and restaurants close by 8 p.m. There’s the single-screen Niles movie theater on Main Street — but it only screens once a day on weekends.

Teenagers go hiking, hunting or fishing in the nearby mountains. They party and drink. Or they drive 100 miles to shop in Klamath Falls, Ore. — where the nearest Walmart is.

Their lives revolve around school: sports, band, Future Farmers of America, drama club.

“As much as this town holds some sadness for me, it’s also formed my whole existence as a person,” Plumlee said this spring. “It is who I am.”

She knew she needed to leave to be happy. But she was nervous to even start applying. What if no one accepted her?

In Modoc County, college — for those who want to pursue it — can feel elusive. About 20% of residents 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree, compared with 35% statewide. There are no community colleges in the county, and the closest California public four-year university is Chico State, four hours southwest.

“It’s scary to move,” said Candace Boudreaux, the counselor at Modoc High School. “We don’t have a lot of kids whose parents have gone to school. A lot live on welfare; that’s the reality.”

Boudreaux, 26, grew up in Redding. She was shocked to learn how little of the world some students in Alturas had seen.

She recently went on a field trip with a group of high schoolers. At the Mt. Shasta Mall in Redding, some said they had never ridden an escalator.

Boudreaux, who also is the cheerleading coach, teared up when talking about Plumlee.

“She’s the definition of resilience. So many of the kids here are,” she said.

The 38 graduating seniors in the Modoc High School Class of 2023 were a close bunch.

In mid-May, they tried to picture life beyond the safety, security — and boredom — of their small high school.

Natalie Bunker, 18, planned to go to the University of Nevada-Reno to study radiology. Or journalism. Or education.

She was bracing herself to make the three-hour drive alone and to navigate city streets in her 2017 Mazda CX-3, which she nicknamed Daisy Buchanan after the debutante in “The Great Gatsby.”

“Learning to drive in a big city is a really daunting task,” Bunker said. “Terrifying.”

About half of high school seniors in Modoc County typically go on to college, compared with about two-thirds statewide.

Like many of his classmates, Daniel Strain — who held down jobs at Les Schwab Tires and Holiday Market — planned to stick around Alturas after graduation and train as a certified nursing assistant at a rural hospital in nearby Cedarville.

It was too expensive, the 18-year-old said, to spend a bunch of money on a college degree only to realize it wasn’t what he wanted to do.

“I don’t want to stay here forever, obviously,” he said. “I want to go live my life and have my own adventures.”

Then there’s Justin Walton, the salutatorian and one of Plumlee’s closest friends.

He enrolled at Bushnell University, a private Christian college more than four hours north in Eugene, Ore., where he planned to study accounting.

Walton — a 17-year-old varsity golfer with a flop of curly brown hair — is such a math whiz that the high school ran out of classes for him.

And he’s a new dad.

Sitting in his parents’ backyard in mid-May, he showed off pictures of Baby Elliott, then 9 months old, at prom the night before, wearing a tiny floral boutonniere Walton had made in an agriculture class. The infant stayed at the dance until just past his bedtime.

Walton had been working a lot more — he was a cook at the Lazy B with Plumlee and a cashier at Holiday Market — to support his baby boy, who will stay in Alturas with his mother, with Walton’s parents nearby.

He said he was ready to leave but intimidated by moving to a city with a population of 178,000.

“I know everybody here,” he said. “It’s going be super weird. Even going to Redding, walking through the mall, just walking past thousands of people that I don’t know and will never see again — it’s crazy.”

“I’m freaking out,” his father, Ken Walton Jr., said. “We’re buddies.”

“But it’s part of the process!” his wife Cherie interjected. “We did the same thing to our parents. We left home. That’s just the way the world works.”

On the school van returning from a Future Farmers of America speech competition, Plumlee got an email that took her breath away.

She had been accepted to UC Berkeley.

She had pulled her grades up — studying early in the morning in the school library before class and late at night after work.

All the while, she juggled multiple jobs. At one point, she was working simultaneously at the county registrar’s office, waiting tables at the Lazy B barbecue and teaching senior citizens computer skills at a local nonprofit.

With some prodding by Boudreaux to be more open about her situation, she wrote college essays about the challenges she faced.

Her first thought was that she couldn’t afford Berkeley. Days later, she learned that she would be getting financial aid, along with so many scholarships that her tuition was paid.

“College for four years — that means a stable place for four years,” she said. “I’m not moving for four years!”

Plumlee has never lived near an ocean, but she plans to study marine biology. “I’m not a very spiritual person, per se, but I’ve always felt very drawn to the ocean,” she said. “There’s so much unknown about it.”

And now, she has the love of a family.

Stephanie Wellemeyer, the Modoc County registrar of voters, took Plumlee in this spring after the teenager quit her job at Wellemeyer’s office and opened up about her situation.

Wellemeyer had a family meeting with her husband, their 8-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter. Bring her home, they said. That’s how Plumlee came to be sleeping in the Disney-themed room of the little girl.

On prom night, Wellemeyer’s husband met Plumlee’s date at the door and told him to treat her right. He went full dad-mode, Wellemeyer said, tearing up.

“She needs it,” Wellemeyer said. “She needs somebody to love her.”

Wellemeyer’s daughter cried when she learned Plumlee would leave soon for college. The family told Plumlee to keep her key so she would always have a home to come back to.

Wellemeyer joked that even though they’re from a deeply conservative county, “we’re Berkeley people now.”

Plumlee graduated on a warm Friday night in June. She had decorated the top of her graduation cap with gold glitter and the words: “She turned her can’ts into cans and her dreams into plans.”

In his salutatorian speech, Walton shouted out “my little man,” who was in the bleachers in a onesie with boats on it.

He “has shown me what challenge truly is, but most importantly, that it’s worth it,” Walton said. “He’s my drive to do better as I try to be the best father to him that I can.”

In the audience, Walton’s dad — who said he would miss his son, his best buddy, terribly — was misty-eyed.

Afterward, he caught Supt. O’Malley, a longtime friend, by the sleeve.

“I thought you were supposed to hold him back a year,” Ken Walton joked.

“He was too smart for that,” O’Malley said.

The Wellemeyers cheered as Plumlee walked across the stage for her diploma. Afterward, their children wrapped her in hugs.

Her mother was in the audience, too.

After most of the gym cleared out, Plumlee walked up to Helen. There was an awkward pause.

Plumlee gave her mother a quick hug. They took a photo together. And she returned to her friends.

George Levines, deputy director for data and graphics, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.