Temecula school district sued over its ban of critical race theory

The Temecula Valley Unified School District faces litigation over a ban it enacted on critical race theory, taking the culture-war battle over classroom instruction about racism to state court.

The suit filed Wednesday alleges that the Temecula board’s ban violates the California Constitution’s guarantee of a “fundamental right” to an education that protects students from racial discrimination. It also alleges that the ban violates state laws that set out mandatory learning standards that include discussions about racism, inequality and how past events are relevant in the present day.

For the record:

10:59 a.m. Aug. 2, 2023An earlier version of this article said that the ACLU filed the lawsuit. Public Counsel filed the suit in partnership with the law firm Ballard Spahr.

Critical race theory examines how racial inequality and racism are systemically embedded in American institutions.

In what he described as a personal statement, Temecula Valley school board President Joseph Komrosky said the district would respond officially “in due course,” while adding, “this suit effectively represents an effort ... to use CRT and its precepts of division and hate as an instructional framework in our schools.”

“I do not believe that CRT or any racist ideology is a suitable educational framework for classroom instruction at the elementary and secondary level,” said Komrosky, who was part of the three-member majority that approved the resolution in December 2022.

The wording of the resolution puts forward a goal “to uplift and unite students by not imposing the responsibility of historical transgressions of the past” and asserts that critical race theory is “an ideology based on false assumptions about the United States of America and its population.”

The suit was filed on behalf of Temecula students, parents, teachers and the local teachers union by the public-interest law firm Public Counsel and the law firm Ballard Spahr.

If the suit overturns the ban, it could have a broad effect in California. Attorneys in other states are also exploring similar litigation, according to attorneys who announced the lawsuit at the offices of Public Counsel in Los Angeles.

Thirty-six states have restricted education on racism, bias or the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history, according to a recent review. California is one of 17 states — including Washington and Delaware — that have moved in the other direction by expanding education on racism, bias or the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history.

In California a small number of districts, including Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified, also have passed bans on critical race theory or otherwise restricted instruction on race.

The Temecula school system has been a recent flashpoint for controversies over what is taught. Gov. Gavin Newsom threatened to fine the Riverside County district $1.5 million for refusing to adopt a state-approved social studies curriculum because there was a mention of San Francisco County Supervisor Harvey Milk, a gay rights leader who was assassinated. The board then reversed course and said it would allow the instructional materials.

The resolution at issue in the suit states that “Critical Race Theory assigns generational guilt and racial guilt for conduct and policies that are long in the past” and “will not constitute the basis for any instruction,” citing the district’s authority to determine local curriculum.

The suit alleges that, through the resolution, the district is depriving students “of the opportunity to engage in factual investigation, freely discuss ideas and develop critical thinking and reasoning skills.” The anti-CRT resolution harms all schoolchildren, the suit states, but in particular “injures children of color and LGBTQ children, stigmatizing their identities, histories, and cultures.”

One female student, a rising high school junior in Temecula, said the impact of the resolution was immediate. Productive conversations about racism, prejudice and bigotry virtually disappeared from her classrooms, she said.

The student, like other plaintiffs, is not named. A letter she wrote was read at the news conference.

Teachers, she added, have been less likely to confront students who make negative comments about students who are different from them. And cultural clubs are now under scrutiny by community members.

“Many club leaders feel unsafe hosting club events or speaking publicly due to the intense polarization of the community,” she wrote in the statement read by Jennifer Scharf, a teacher at Great Oak High School.

The Temecula district serves about about 28,000 students in the city of Temecula and nearby areas. About 39% of students are white, and nearly 60% are students of color — 36% Latino, 10% two or more races, 5% Asian, 5% Filipino and 4% Black.

Donald Trump received nearly 53% of the vote in the 2020 presidential race in the Temecula area.

Board member Steven Schwartz, who opposed the ban, said the resolution “was the cause of student walkouts and was disruptive to TVUSD. It caused a great deal of stress to students and teachers.”

Immediately after the resolution passed, said Scharf, Black students asked her anxiously: Can they talk about the systemic racism they’ve experienced walking around stores or with police officers? Are they allowed to raise their hand when they relate to a character in a novel? Can they speak their truth?

“I told them: ‘You keep telling your story,’” Scharf said.

One parent said she is taking part in the suit because the resolution “robs my son of educational opportunities that he has every right to.”

Before the resolution was passed, her son’s elementary school class watched Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech for Black History Month. He came home from school with questions about race, she said, and the two had a robust discussion.

The next year, after the resolution, there were no lessons around Black History Month, she said.

“I believe the loss of learning will only be compounded as he advances through the grades,” she said.

After the resolution, a rising senior said she arrived to an altered AP U.S. History class: “My teacher said, ‘I’m not sure what I can teach you guys anymore.’” Her teacher showed videos on slavery but avoided a class discussion.

Teachers said they’ve taken extra precautions after facing backlash for speaking against the resolution at board meetings. Scharf put in a second security camera at her house. Dawn Murray-Sibby, a teacher at Temecula Valley High School, no longer posts on social media.

Some of their colleagues have been doxxed, their home addresses and phone numbers posted to the Internet.

“It’s scary,” said Murray-Sibby. “I’m not exactly sure what I’ve gotten myself into, but I know I am on the right side of history here.”

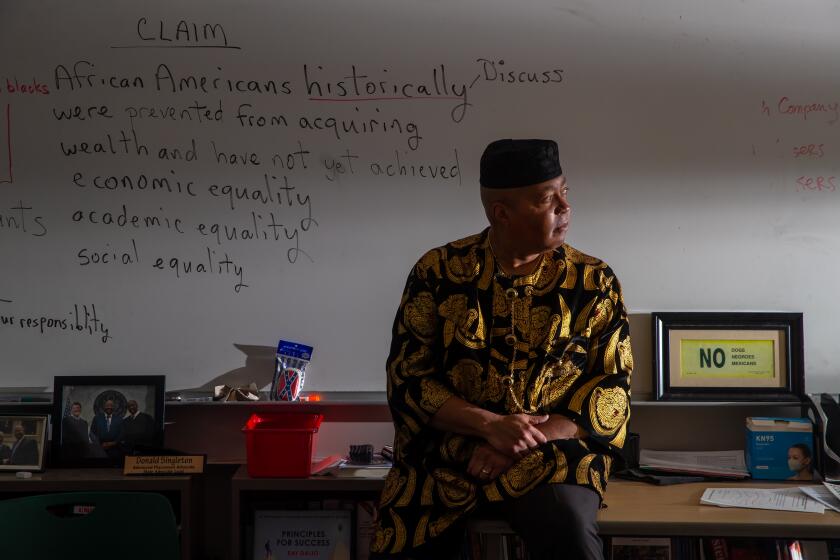

Reparations, Black Panthers — no topics are off limits in this AP class on Black history. Pupils say they’re now more likely to vote and be involved in their communities.

The term critical race theory has become a catch-all phrase and a rallying point for critics who want to limit discussions on the history of racism, systemic racism and racism in the current time. Critical race theory was developed at the college and graduate level to examine systemic racism, including in the present day. While the term critical race theory was, until recently, used almost exclusively in higher education, concepts about racism that it embodied have been on the table for discussion in high school social studies classes for years.

The term has become embedded in the nation’s ongoing culture wars, with critics embracing an anti-CRT stance as a plank in their activism against what they view as harmful liberal values.

The resolution also banned specific elements of instruction.

Teachers will be unable to engage students in discussions on whether “racism is ordinary, the usual way society does business,” the resolution says.

The teaching ban also includes the “doctrine” that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist and/or sexist, whether consciously or unconsciously” and that “individuals are either a member of the oppressor class or the oppressed class because of race or sex.”

Under the district resolution, there could be one strictly limited way to talk about critical race theory. The discussion must play only a subordinate role in the overall course” and must focus on the flaws in critical race theory.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.