Board votes to ban critical race theory in Placentia-Yorba Linda school district

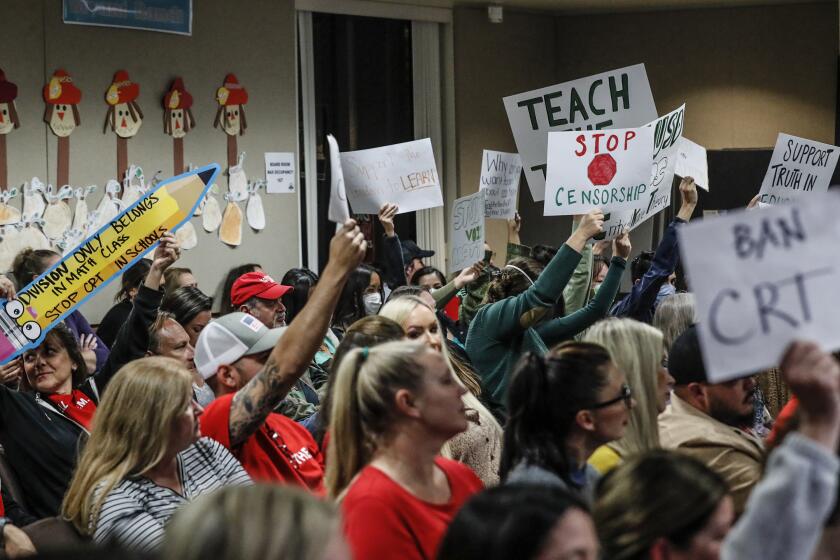

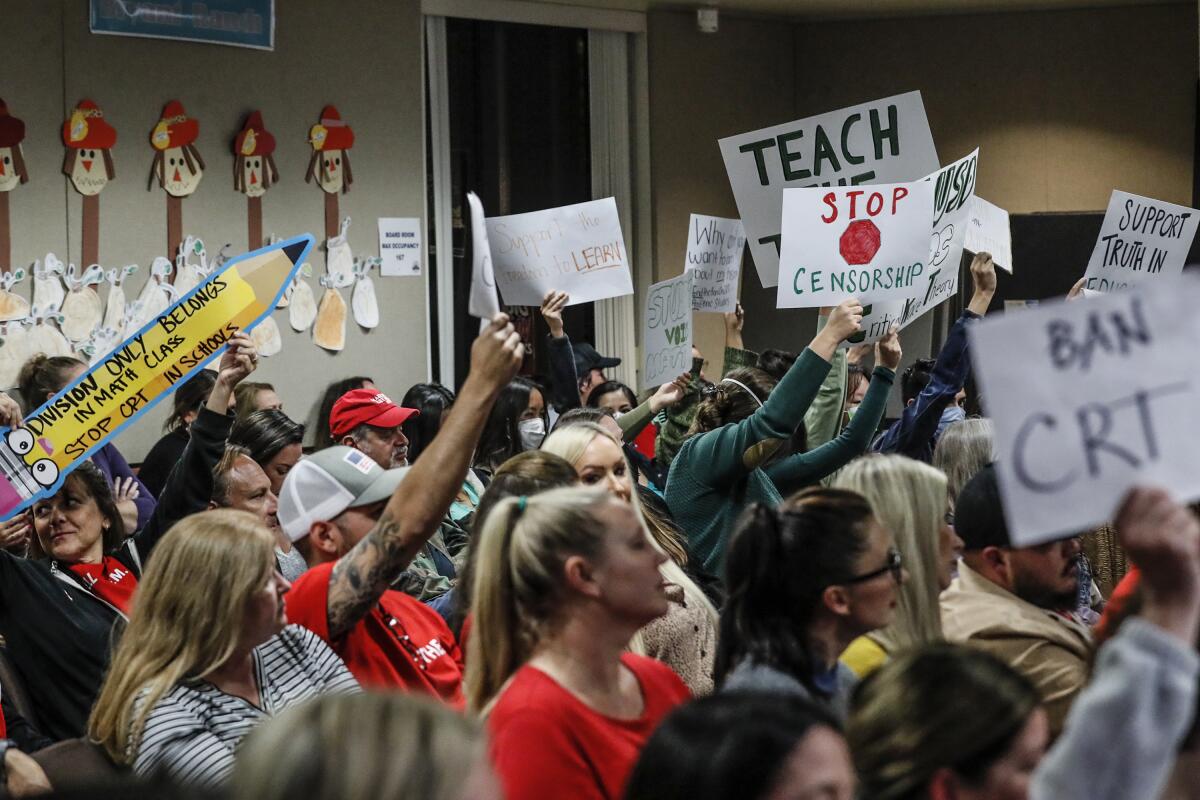

A divided Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District board voted late Tuesday night to ban the teaching of critical race theory in its classrooms, ending months of contentious debate in the Orange County school district.

The 3-2 board vote came after pointed comments from trustees, two of whom called the measure censorship. Supporters, however, said parents should be the ones who decide what to teach their children about race.

“I don’t want my politics, I don’t want your politics, I don’t want anybody’s politics in [classrooms],” said board member Leandra Blades, who supported the ban. “I do believe in teaching kids to think critically. But there are so many classes ... there are so many things you could teach your kids at home. If you really are passionate about these subjects, then teach them.”

Approved after an hour of in-person public comments — with more than half expressing opposition — the resolution encourages culturally relevant instruction and states that the district “values all students and promotes equity and equality.” But the school district will “not allow the use of critical race theory as a framework to guide such efforts.” The resolution also states “other similar frameworks” will not be used to guide teachings on race, but these teachings were not identified.

Blades argued against statements from other board members who said the resolution was politically driven and would censor educators. Last year, Blades faced calls to resign after attending the rally outside the White House on Jan. 6, 2021, that preceded the violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Board President Carrie Buck, who opposed the ban, said teachers and students were largely against it.

“This is the first time in the 12 years I’ve been here that I’ve had 105 students send me an email or call me or send me messages saying, ‘Don’t do this,’” said Buck.

Board member Karin Freeman, who also voted against the ban, called it “misleading” at best and an abridgement of free speech and censorship at worst.

“This change creates obstacles and impediments for students’ success,” Freeman said. “If students aren’t able to have access to rigorous coursework, the impact will be real.”

An Orange County school district’s debate over critical race theory exemplifies how a hard-to-define academic concept has become a proxy for uncomfortable conversations about racial injustice in the U.S.

It is not clear if the district has recorded instances where critical race theory has ever been taught in a classroom.

But the resolution comes at a time when an increasing number of states have passed laws that ban or restrict the teaching of critical race theory in K-12 schools. The resolution does not say whether educators will be punished if they discuss it in their classroom. The board discussed a process where, if parents are concerned that critical race theory is being taught, they can complain to the school principal, who will then investigate.

Critical race theory is a university-level academic framework that seeks to examine how racial inequality and racism are historically embedded in legal systems, policies and institutions in America.

The once obscure academic theory has been pilloried recently by Republican activists and lawmakers who seek to restrict how race and racism are taught in classrooms — saying that it teaches that white people are racist oppressors and people of color are the oppressed. Democrats say the campaign against it is meant to restrict broader discussions about the country’s history.

The speakers Tuesday night reflected the deep divide. The vast majority of students who spoke criticized board members who support the ban, saying it would limit critical thinking and discussions among their peers. And in one particularly passionate comment, a pair of eighth-graders from Kraemer Middle School presented a petition signed by more than 550 middle school students — about half the school — who opposed the ban.

“Teaching race-related topics is not about blaming any one group. Instead, it is trying to understand different perspectives, especially those different from our own, so we can understand how past history affects our current society,” one of the eighth-graders said. “This is critically important for us, as the next generation, to not repeat past mistakes.”

Another student, who said they have appeared before the school board four times to oppose the ban, said she has been yelled at by parents who say she doesn’t know what racism is and “that I hate my country.”

“If you say teachers are oppressing white students, then ban racism,” the student said. “Ban something substantial.”

One student vowed to do everything to reverse their decision.

Parents who spoke in favor of the ban said they believed it was already being taught in schools and their children would be harmed by the teachings. One parent called for teachers to sign copies of the ban so the consequences “are very clear from the get-go” and they be kicked out of schools if they were caught intentionally teaching it, like students who violated masking mandates during pandemic restrictions.

“We need to preserve our history and not blame anybody and move forward and stop dividing this country,” said one parent who supported the ban. “Everybody wants to pick a side. Stop picking a side and pick the side of the future.”

The district has had a prolonged debate over the topic of critical race theory, at one point spending hours over how to define it in the proposed resolution. Other school districts in Orange County have also debated ethnic studies and critical race theory’s role in the course.

Ethnic studies is now required for future graduating California high school students. A look inside what students talk about in ethnic studies classes.

Ultimately, the district settled on the definition put forth by the California Board of Education, which describes it as “a practice of interrogating race and racism in society.” Critical race theory recognizes that race is a social construct and acknowledges racism is embedded within systems and institutions that perpetuate racial inequality.

The American Historical Assn., a membership organization of professional historians that defends academic freedom, wrote to the school board in January expressing its concerns about the resolution.

“Critical race theory is usually not taught in K–12 classrooms. Why explicitly mention this theoretical construct and not others, since there is a nearly infinite universe of theoretical approaches that are currently not taught in the district but might be objectionable to different people for different reasons?” executive director James Grossman wrote, adding that American history curricula and textbooks have long distorted the past, such as portraying Confederate leaders as heroes and omitting the role of racism in American institutions.

Grossman questioned whether critical race theory has ever been a part of the district’s curriculum.

While California lawmakers have largely advocated for deep discussion about race in the classroom by requiring ethnic studies for all California high school graduates starting in 2030, some school districts have become battlegrounds for contentious anti-critical-race-theory activists.

In July, the Orange County Board of Education hosted a forum for parents to ask questions about the state’s new ethnic studies curriculum.

A panel of scholars was put together by the conservative-majority board, but one prominent panelist, Theresa Montaño, who advised the state board on the ethnic studies curriculum guidelines, declined to attend.

Montaño, a professor at Cal State Northridge, said that critical race theory is not discussed in K-12 classrooms, but discussions of race remain an important subject matter for all children.

“No amount of censorship or school district resolution will erase the reality of racial inequity, racial trauma and systemic racism,” Montaño said of the board’s Tuesday vote.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.