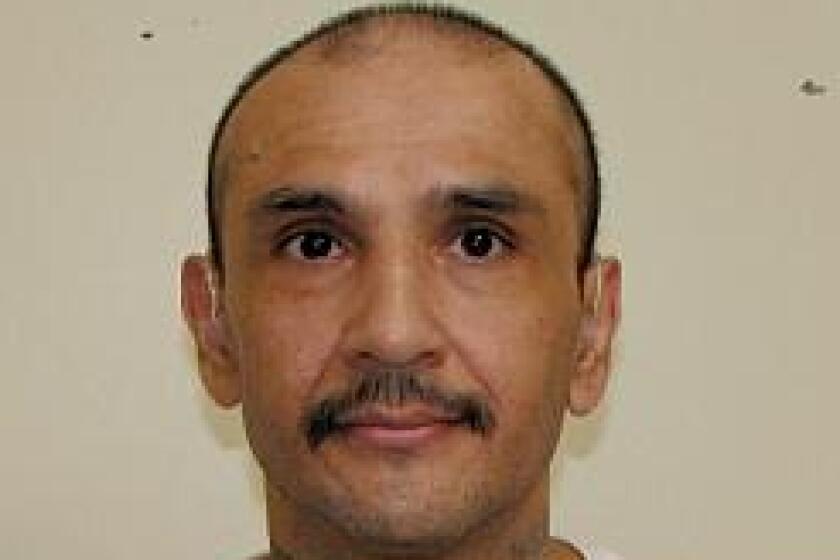

‘Big Evil’ was ‘programmed to kill’ in L.A. Now he’s eligible for parole after plea deal

A notorious Los Angeles killer from the 1990s known as “Big Evil” is eligible for parole after serving more than 25 years on charges that once landed him on death row.

Cleamon “Big Evil” Johnson, 55, pleaded no contest and was convicted Thursday of a sole count of murder in a case stemming from five murders in the early 1990s, when he was the leader of a small but disproportionately violent subset of the Bloods — the 89 Family Swans — in South Los Angeles.

Johnson was once on death row at San Quentin State Prison for two of the five killings, but racist comments made by the lead LAPD detective on the case prompted a judge to decide that Johnson would no longer be subject to the death penalty or life in prison without the possibility of parole if he was convicted at retrial.

The convicted killer has already been in state prison more than 25 years, meaning he is eligible for parole now, though that does not mean he will be granted it.

“I was on this case for 16 years and I’m very pleased with the outcome,” said Bob Sager, Johnson’s defense attorney.

In 2014, LAPD Det. Brian McCartin used a racial slur while out with colleagues at a bar. Only recently did the D.A. office let many defendants know

Johnson’s no-contest plea Thursday came for the killing of Payton Beroit, who was gunned down along with his friend, Donald Loggins, at a carwash on 88th Street and Central Avenue in 1991.

While Johnson pleaded no contest to the Beroit murder, charges were dropped against him in the killing of Loggins along with three others: Albert Sutton, Georgia Jones and Tyrone Mosley.

Johnson’s case has been bouncing around the legal system for decades, with the California Supreme Court tossing his conviction in 2011 over a juror-related issue from his initial trial.

But in 2014 the lead LAPD detective on the case, Brian McCartin, used the N-word when referring to Black gang members while hanging out with a deputy district attorney and a public defender. The information was not turned over to Johnson’s defense until 2018. The comments became a flash point in Johnson’s case. In May 2022, the judge on the case ruled that McCartin’s comments and the four-year delay in turning them over to the defense was unfair to the defendant.

The past caught up to Donald Ramon Ortiz the afternoon of Nov. 19, 2021. It came disguised as a detective, holding a gun in a gloved hand.

“Many unfortunate things happened in this case and it’s discouraging,” said Jon Lipsky, an FBI agent who worked the case in the 1990s.

Though Lipsky said Johnson is a “stone-cold killer,” he also believed that McCartin’s comments and the failure to turn them over expeditiously was a legal violation.

“I believe in the rule of law,” said Lipsky, speaking about the sentence of 25 years to life. “I think it’s a fair and just determination.”

When Ezequiel Romo came home to Panorama City after 18 years in prison, he didn’t like what he saw. He told another veteran of his gang, Blythe Street, he was going to “clean out house.”

Still, Lipsky recalled Johnson as an “anomaly” in the Los Angeles gang world in the 1990s. While serving time at Ironwood State Prison in Blythe for a drug charge in the early ‘90s, Johnson ran his gang with violent efficiency, Lipsky recalled, ordering hits in code on phone calls. The breadth of the killings Johnson and his gang were accused of committing was astonishing, Lipsky said.

“It was unparalleled,” he said.

The single count of murder that Johnson is now legally responsible for is a far cry from what police once accused him of. Police attributed “more than 20” murders to Johnson and his crew, according to a report in The Times in 1998. Johnson himself admitted to 13 murders at the time, Lipsky said

In 1998, Johnson told The Times that he was like an American soldier sent to “Vietnam ... programmed to kill.”

“We couldn’t stop killing our enemies here, either. I was one of them sick individuals. They locked us away, but we needed help mentally,” he said. “I was the epitome of a gang member. I was real. ... Some people worshiped Allah or Jesus. I worshiped Bloods.”

El Salvador’s evangelical churches rehabilitated ex-gang members. The country’s crackdown on L.A.-born gangs like MS-13 emptied programs and filled prisons.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.