SAN SALVADOR — The MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs fought on the street outside Eben-ezer Baptist Church for years. Neighbors lost children. Pastor Nelson Moz led prayer services over the crackle of gunshots.

When a young man just out of prison came to Moz in 2012, saying he’d found God and wanted to leave his gang, the pastor agreed to help. Moz put a mattress in his church office so the budding evangelical could stay out of the gang’s path.

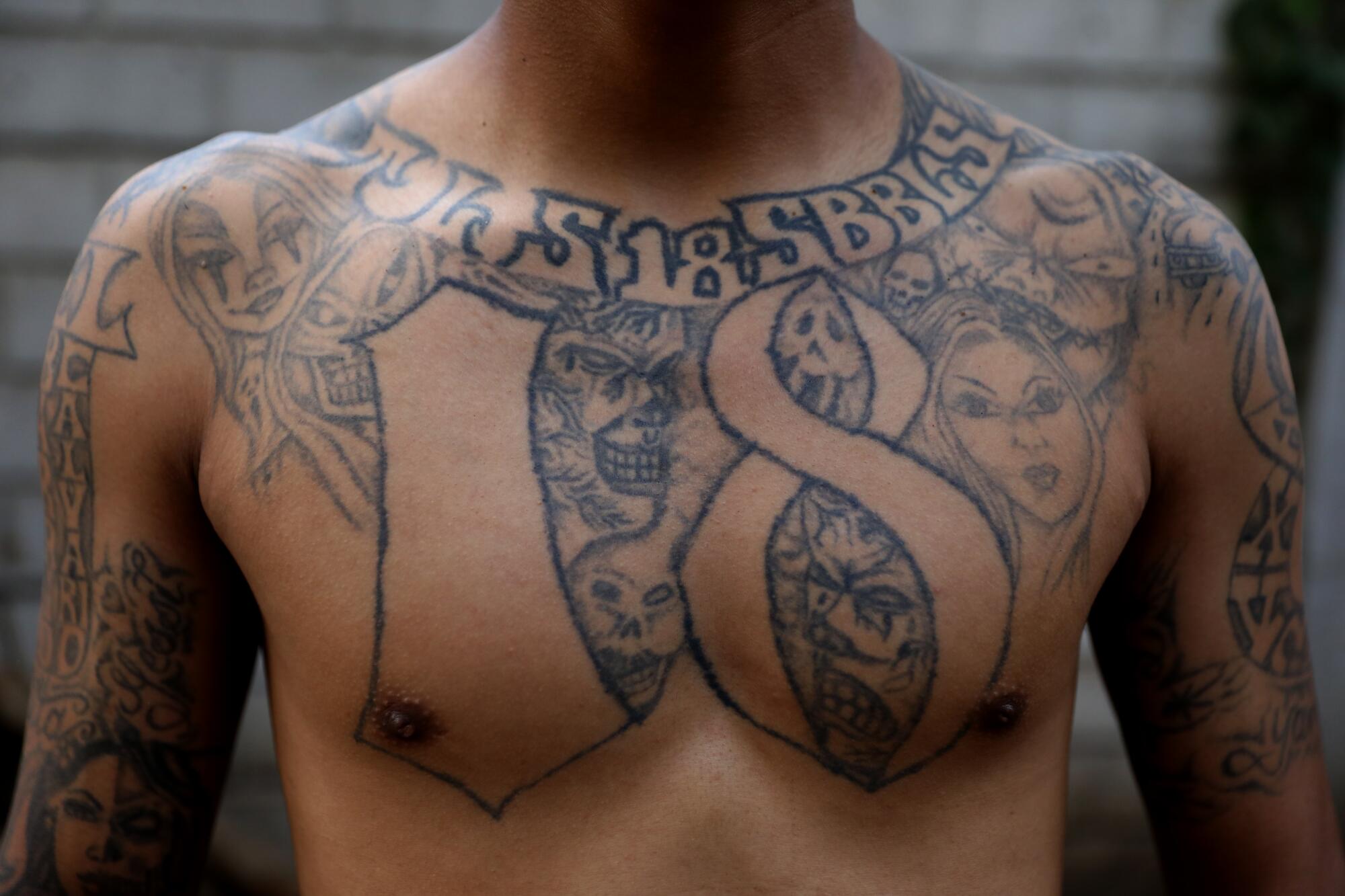

Word soon spread, and others seeking to abandon their criminal lives started showing up at the church, in a working-class San Salvador neighborhood. Mattresses crowded the floor, eventually replaced by bunk beds. The men, covered in gang tattoos, made pastries and garlic bread out of a makeshift bakery in the church’s basement. They walked gang neighborhoods, preaching the Gospel through megaphones.

Twenty-five men at a time stayed at the church. Dozens more filtered through, seeking redemption.

Last spring, it all came to an abrupt halt.

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele declared a crackdown on gangs, directing lawmakers to pass a state of emergency suspending some constitutional rights. Police started arresting anyone who might be connected to a gang, including former members in rehabilitation programs such as Moz’s.

Bukele’s crackdown is a hit with his compatriots. With more than 67,000 people arrested and a sharp drop in homicides, Salvadorans today say they feel much safer. There’s little attention paid to the evangelical pastors who believe gang members can change.

“Nothing is happening; none of them are getting out,” Moz said of his imprisoned parishioners, as he walked past two dusty ovens pushed against a wall in the Eben-ezer church basement.

Bukele is unapologetic for his approach on gangs.

“These pastors are right: God can redeem anyone. God and God alone can forgive their sins and save them,” he tweeted Wednesday in response to an earlier version of this story. “If God forgives them, they will enjoy eternal life. But here on Earth they still must face the consequences of their actions.”

L.A.-born gangs ruled El Salvador

The gangs that have long dominated life in El Salvador formed in Los Angeles. Barrio 18 and Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, were transplanted to El Salvador in the 1990s, when the U.S. deported thousands of Salvadorans. For decades they controlled neighborhoods through extortion and violence.

With his carefully crafted social media presence and populist politics, Nayib Bukele has become one of the most popular politicians on Earth. Now just one question remains: What does he want?

The country fought back with mass arrests, but the gangs ended up organizing in prisons. The government helped to broker a gang truce, but it collapsed, triggering violence that left El Salvador with one of the highest homicide rates in the world. In 2015, it reached more than 100 killings for every 100,000 residents. The government labeled gangs as terrorist groups, but the killings continued.

As prisons filled and pastors proselytized inside, some gang members began converting to evangelicalism, a growing movement in El Salvador that preached the power of repentance.

Gangs sometimes let their members leave if they were sincere about their conversion. The pious lifestyle that churches encouraged let gangs easily monitor their former members, said Jose Miguel Cruz, a gang expert at Florida International University.

“The gang still considers you a threat, a risk, a potential competitor,” said Cruz, who surveyed almost 1,200 active and former Salvadoran gang members and found that adhering to religious life is the most accepted way to leave a gang.

When Moz began housing former gang members at his church, friends warned that he could be arrested. Rumors spread that he was “a pastor for gang members.”

Several families left the congregation, including Moz’s own mother. Others warmed to the newcomers as they saw them living respectfully in the church.

Moz required the men to participate in church activities, expected them to begin removing their tattoos and forbade communication with their old gangs.

Several were killed when their gang felt that they weren’t committed to their new life, perhaps after spotting them drunk on the street, he said.

“We’re very sorry, but this one didn’t walk right,” the gang would tell him.

The ex-gang members would stay in the two-story church a few months, or several years, Moz said. One occupant, Julio, completed a theology course and worked at the church’s convenience store.

At Sunday services, dozens of ex-gang members filled one side of the large room. Those working at the bakery rode bicycles through nearby neighborhoods to sell their bread, wearing shirts with the church’s name.

But the men attracted attention. Police raided the church several times, checking the IDs of ex-gang members and briefly hauling some away.

“It was a time of great difficulty,” Moz said. “But there wasn’t room for fear. It was more the wish, the passion for change.”

Moz worked with pastors at other churches to establish several more halfway houses. He traveled to Los Angeles to visit Homeboy Industries, whose gang rehabilitation program provides tattoo removal, legal services, counseling and job training to thousands every year.

In 2019, the U.S. Agency for International Development began working on a program for people who said they had left or were trying to leave a gang. The agency teamed up with Moz’s church and two others to provide job training and counseling. USAID also supported La Factoria Ciudadana, a rehabilitation center west of San Salvador that worked with about 300 people a month from churches and the prison system.

They had high hopes to expand the rehabilitation efforts.

A state of emergency

In March 2022, a three-day gang rampage left 87 people dead. The violence is widely believed to have followed the collapse of a secret truce between the government and gang leaders, which Bukele has denied ever existed.

Journalists in El Salvador who write about gangs can now be sent to prison. Two brothers defy the law with a story tying President Nayib Bukele to violent street gangs.

The state of emergency that followed suspended civil liberties including the rights to know the reason for one’s arrest and to appear before a judge within 72 hours. Congress expanded pretrial detention and enacted 30-year prison sentences for gang members and those supporting gangs.

Soldiers swarmed neighborhoods, arresting those with gang tattoos or past convictions, or people they considered suspicious. On Twitter, Bukele posted video of prisoners — barefoot and clad only in white boxer shorts — running, crouched, with their hands cuffed behind them in a new mega-prison.

Bukele’s government says the roundups more than halved the number of homicides, from 1,147 in 2021 to 495 last year. Experts agree the number of killings has decreased, but some local news reports accuse the government of overstating the reduction.

President Nayib Bukele faced international condemnation after his supporters moved to fire a third of the nation’s judges and clear the way for Bukele to seek a second term.

Salvadorans now visit neighborhoods that were off limits: Previously, if they lived in one gang’s territory but crossed into the turf of another, they risked being killed.

The crackdown has boosted the popularity of Bukele, whose authoritarian tendencies have alarmed U.S. officials. He’s targeted critics and journalists and his government has ousted Supreme Court judges and intimidated anti-corruption prosecutors. But in El Salvador, the president holds a 91% approval rating, according to a survey by the Salvadoran news site La Prensa Gráfica. He plans to run for reelection next year even though the country’s constitution bans consecutive terms.

In an artisanal market in San Salvador’s historic center, people buy key chains, jerseys and aprons — all adorned with Bukele’s face. One large wall decoration features Bukele, a clock and the words: “The president that’s making history.”

“It’s like a dream, it’s the best thing that has happened,” shopkeeper Ceci Martínez said of Bukele’s gang crackdown. “We’re not locked in, the streets are calm, people go for walks, tourists visit us.”

Martínez said she doubts the sincerity of gang members’ evangelical conversions. She began crying as she told of how her son, Luis David, was killed several decades ago, when he was 18. He had moved into a neighborhood controlled by MS-13. He left behind a nearly 1-year-old child, whom Martinez helped to raise.

“The critics are the ones who haven’t lived what we have lived,” she said.

But the state of emergency has alarmed human rights groups.

Officials have detained hundreds of people with no connections to gangs in indiscriminate mass raids, Human Rights Watch and the Salvadoran human rights group Cristosal said in a December report. Some police commanders appeared to have set daily arrest quotas, the report says, and hearings of hundreds of people at a time have made it difficult for attorneys to present evidence.

Security experts point to the failures of past repressive approaches to gangs.

“This is not a solution to the problem,” said Mark Ungar, a political scientist at Brooklyn College who has researched gang extortion in Central America. “It may be a stopgap measure to stop the bleeding, but you’re not dealing with the inherent causes of crime,” such as poverty or police corruption.

In an interview, El Salvador’s vice president, Félix Ulloa, denied the practice of arbitrary detentions and said that the crackdown “has returned peace to the communities,” insisting that residents no longer fear gang retaliation for reporting crime.

“There’s harmony, you see people smiling now, the same people that had been anguished because their daughter was raped ... because they killed their child when they left school,” he said. “People aren’t living these experiences anymore.”

Ulloa acknowledged that more than 3,000 prisoners have been released because they weren’t connected to a gang or were arrested by mistake. He said the decision on whether ex-gang members should be tried will be made by judges. He added that those running rehabilitation programs should notify officials.

“If you do it in the shadows, hidden, it’s most likely that the authorities will think it’s a refuge for terrorists,” he said.

Several pastors interviewed said that no one in their rehabilitation programs had been released after arrests.

Of the 59 people in the USAID program before the emergency decree, 41 are in prison, as are many who passed through La Factoria Ciudadana. Police also targeted a rehabilitation program run by a U.S. missionary in the Santa Ana region and arrested five young, tattooed men.

‘He was trustworthy, transformed’

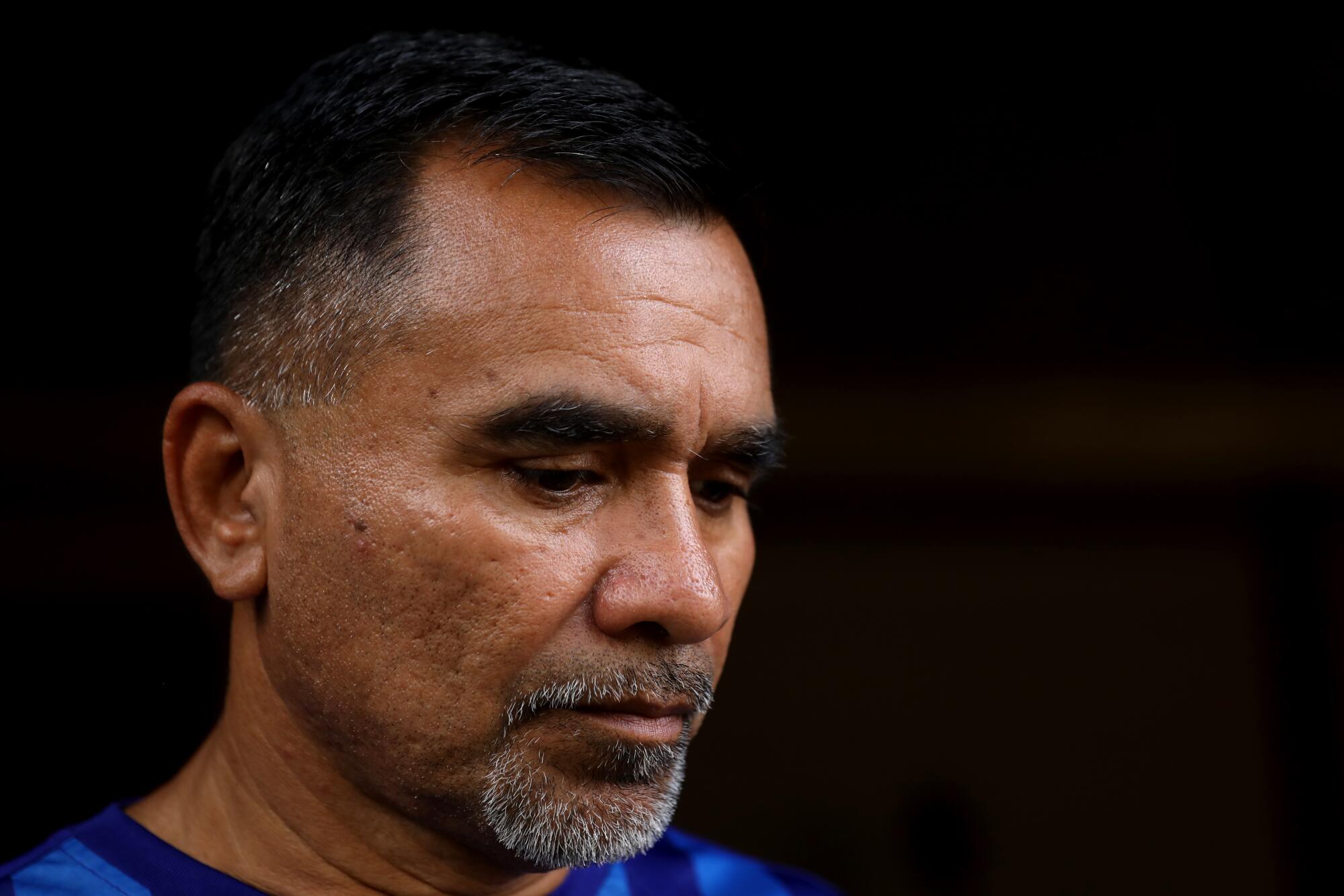

Pastor Edwin Guzmán’s inspiration to reach out to gang members came from an unlikely source: a 1970 American movie, “The Cross and the Switchblade,” starring Pat Boone as an evangelical pastor who ministers in a crime-ridden Brooklyn neighborhood. Guzmán saw the movie years later and said the message stayed with him.

At his evangelical church in San Salvador, Guzmán created a job training program in which former gang members manufactured liquid soap. Everyone in the course was arrested in the crackdown. So were dozens of parents with kids in the church’s after-school program.

Guzmán cried as he talked about Armando, who left MS-13 after he began participating in the church’s youth group in the mid-2000s. At the time, Guzmán let him live in the church and gave him the keys.

“Some were against it, but I said no. I said that if we didn’t believe that God could change these people, then who was going to believe?” he recalled.

Armando was arrested last spring after working as a church handyman for 17 years.

“He was trustworthy, transformed,” Guzmán said. “God had done his work in him. Armando was and is a good person.”

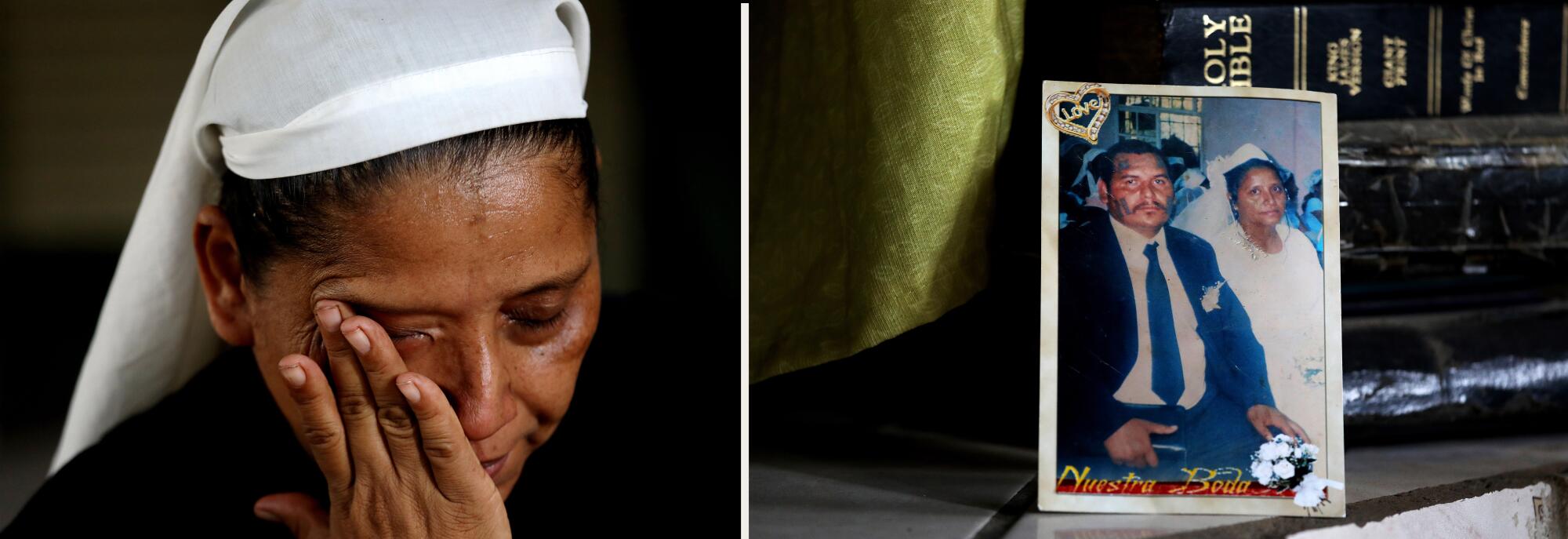

An hour away, in the country’s La Libertad region, José Elvis Reynoza’s one-room evangelical church sits off a dusty dirt road. His family lives next door in a tin-roof home, with the words “The blood of Christ has power” painted on an exterior wall. Two large pregnant pigs laze in an adjacent pen.

Reynoza joined MS-13 as a teenager, became a leader and spent several years in prison. He left MS-13 as a young adult after he began attending church, and for years he led a ministry of ex-gang members who’d preach in local markets.

Reynoza’s tattoos — “Salvatrucha” is emblazoned across his forehead — drew attention. Police often stopped him on the street.

They arrested him at his home in March 2022 as the sweeps began. Officials posted Reynoza’s photo on Twitter, saying he would be tried for belonging to a terrorist organization.

Every 15 days, Reynoza’s wife, Francisca, sends him $100 care packages, hoping they make their way to him. She earns $10 a day at most selling clothing displayed on racks outside their home.

Authorities returned to the house a week after Reynoza’s arrest, asking Francisca if she’d ever been in prison. “Because we’re also taking wives who collaborate,” they told her.

The family has gathered letters from other churches vouching for Reynoza. They worry about his diabetes and, like the families of many prisoners, have gotten no information about his condition.

“When people ask how is the pastor, we can’t say anything,” said Mario Portillo, Reynoza’s 24-year-old son, who has taken over as the church’s pastor. “We don’t have a response.”

Fleeing to Southern California

The risk of arrest was too great for some to stay put. After months of dodging authorities, Nelson Sanchez left behind his wife and three children and fled to California.

Sanchez, 39, had joined MS-13 at 14. When he was released in 2008 after a months-long stint in prison that he described as a wake-up call, he told his gang he was stepping away to search for God.

“We’ll see if it’s true,” they told him.

Shortly after, he said, he was attacked, shot by gang members angry with his choice.

Back then, Sanchez lived by Guzmán’s church, and the pastor let him do maintenance work. He became a youth pastor, took theology courses and helped Guzmán reach out to young people through a neighborhood soccer tournament. In 2019, he began leading his own congregation.

In May, police showed up at Guzmán’s church asking for “Nelson.” Sanchez left El Salvador that month. He turned himself in at the U.S.-Mexico border in June and, after telling his story to a judge, was granted parole, a temporary permission to enter the country.

In his asylum application, he wrote that “the El Salvadoran government is looking for me to take me back to prison and if I fall back in prison there is no doubt in my mind that the MS will kill me.”

Sanchez now lives in Los Angeles with two of his siblings, waiting for his case to proceed.

“To a certain extent I support that the president is yanking the gang problem by its roots,” he said. “But what is not good is that he doesn’t know how to distinguish between the active gang members and the ones who are not active.

“For 16 years I’ve been in a totally different world than the one I belonged to because God gave me the opportunity to repair my life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.