SACRAMENTO — Leer en Español

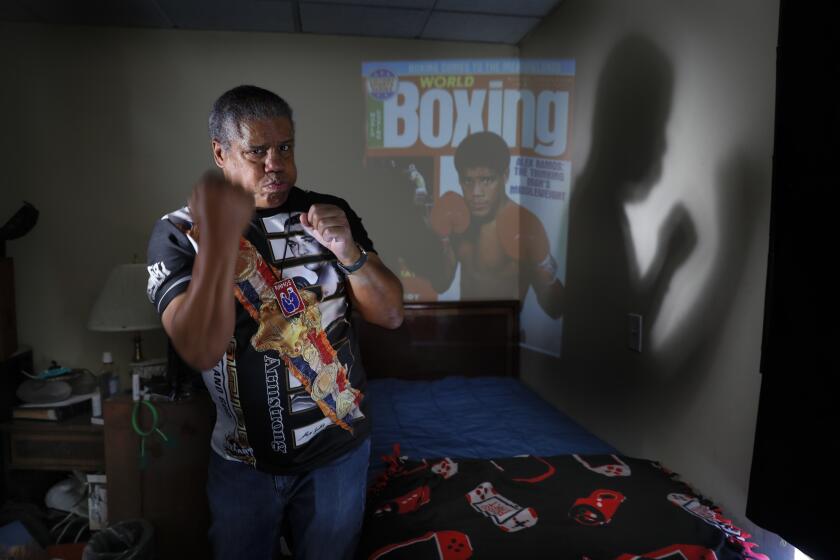

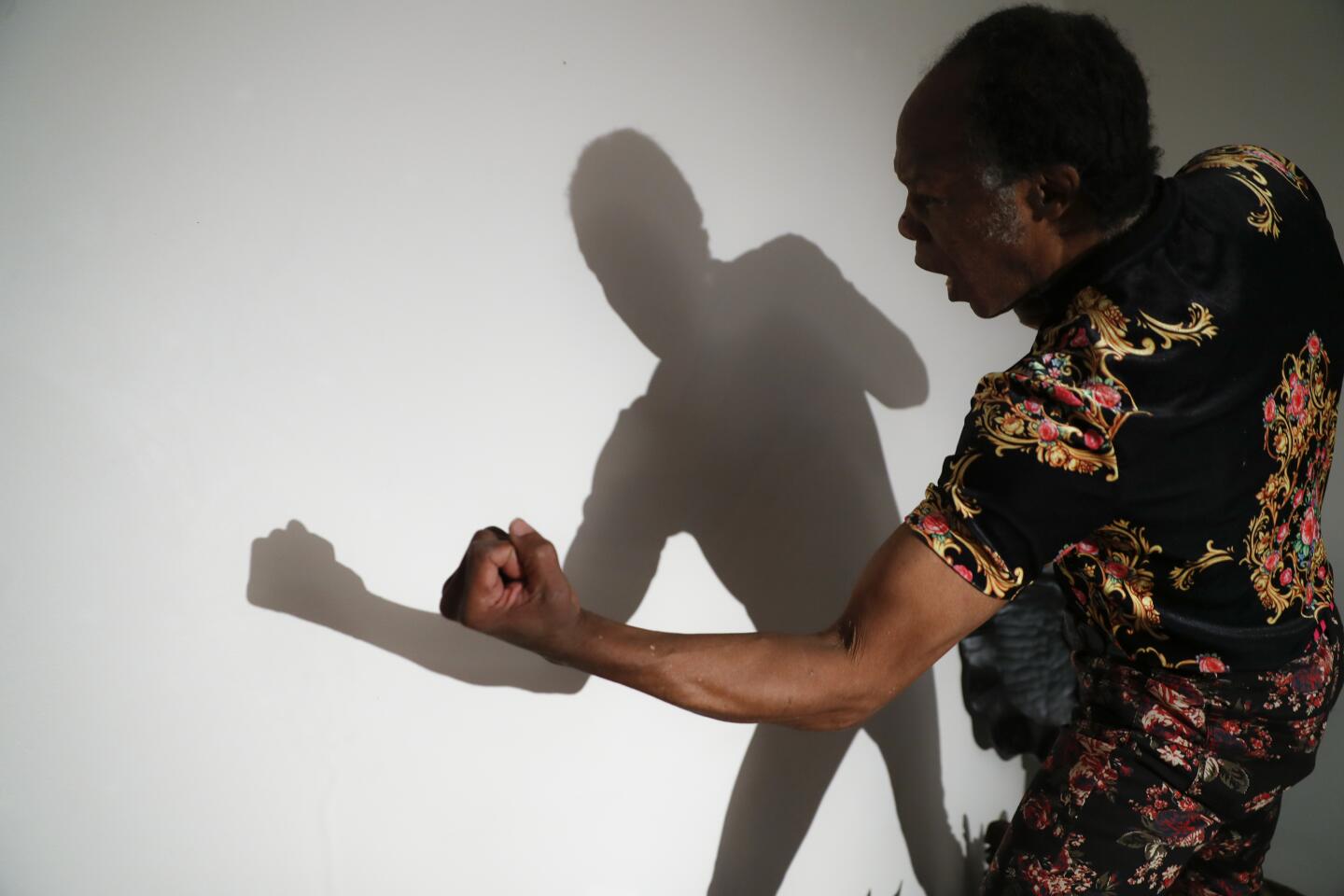

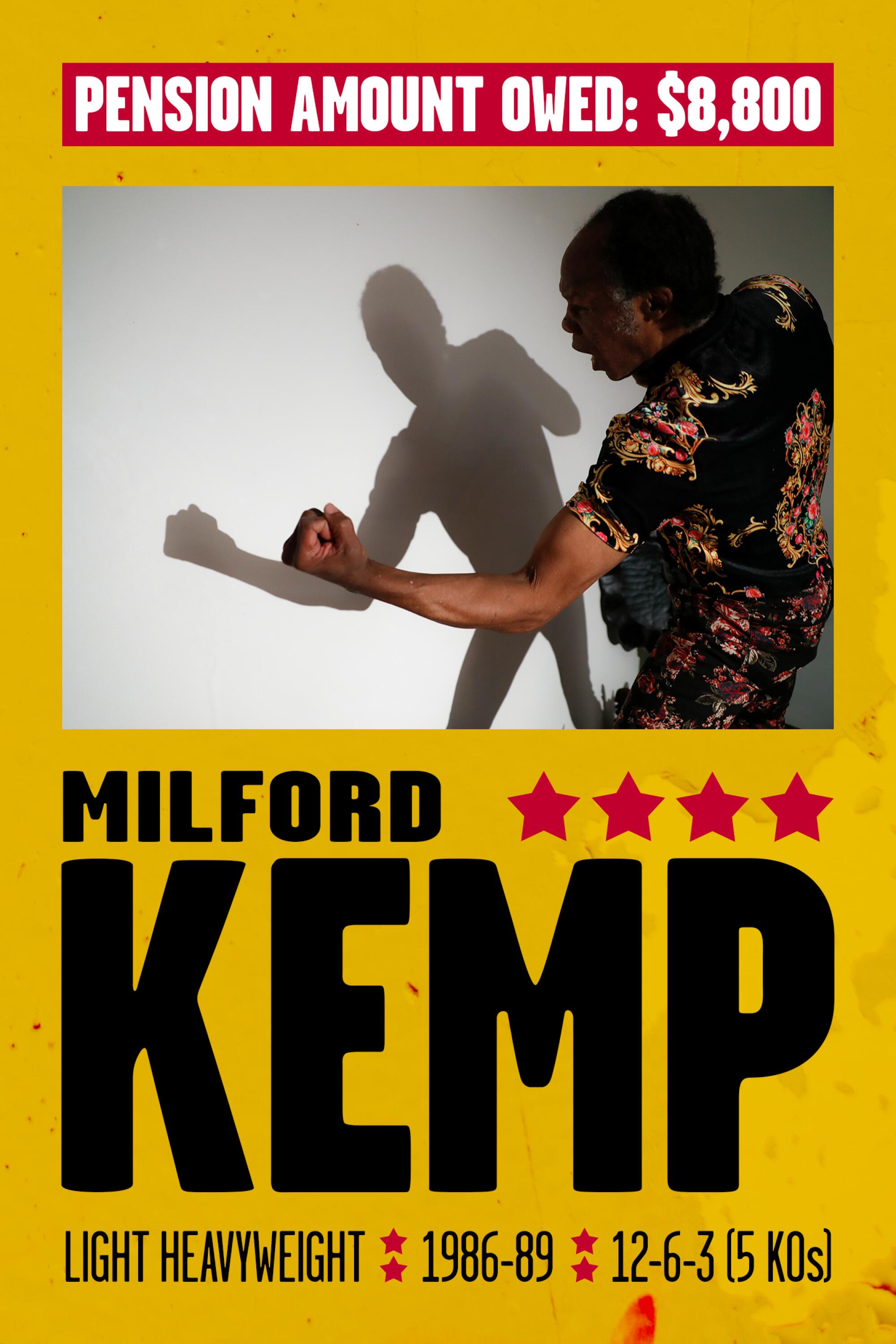

There are days when Milford Kemp’s mind can’t leave the boxing ring. At 69 years old, he relives fights in an endless loop, replaying each blow from memory as his large fists rhythmically reenact his words.

He was briefly known around Los Angeles in the 1970s as the “Ballet Boxer” for his improbable path from college gymnastics and dance to professional boxing. That was before the sport took some of his eyesight. Before dementia robbed him of his short-term memories and stranded him in his perfectly preserved past.

The California Professional Boxers’ Pension Plan, the nation’s only state-administered retirement plan of its kind, was designed specifically for fighters like Kemp — a safety net for the sport’s most vulnerable.

But Kemp said he was never told he had a pension. So it’s remained unclaimed for nearly two decades.

More than a dozen boxers contacted by The Times said they too were unaware they were beneficiaries of the 40-year-old pension program. Many retired boxers said they could not recall ever receiving information from the California State Athletic Commission, which administers the plan, informing them that they qualified or how to apply.

The boxers’ pension plan began making payments to eligible boxers in 1999 and, to date, has provided 235 retired fighters a total of $4 million. Most of that has been paid in the last decade.

But an additional 200 boxers are owed pensions and have not claimed them because, in many cases, they were unaware they were even eligible. And, under plan rules, those unclaimed pensions — which are paid in a lump sum — have been diminishing in value for years, in some cases decades.

“I’m not a hard guy to reach,” Kemp said from his sparsely decorated apartment in Edmonton, Canada, where he sleeps on a discarded massage table he found in an alley. “My phone never rings.”

The Times examined hundreds of state documents and interviewed dozens of fighters, promoters and retirement plan experts about the California boxers’ pension, which includes retirement accounts for more than 1,900 current and former boxers.

When creating the safety net in 1982, California lawmakers said too many fighters were ending up “injured or destitute, or both.” The boxers’ pension, funded by a ticket fee for boxing events, would ensure a “modicum of financial security,” according to language in the state statute.

But a Times investigation found that the pension plan has a long history of falling short of that lofty goal. Among the findings:

- Roughly 200 boxers could have claimed a pension last year, but only 12 of them — 6% — did so.

- The commission has failed to increase the amount of revenue generated for the pension to ensure the plan is adequately funded and benefits do not depreciate over time.

- The plan does not have enough money to pay all unclaimed pensions without reducing the amount of money received by fighters who become eligible in future years — with just $294,000 set aside for the $2.1 million owed to boxers who haven’t been paid.

Experts said the commission has created a sizable unfunded liability and — perhaps more concerning — a disincentive to find boxers who are owed benefits.

California offers pensions to any professional boxer, regardless of residency, who fought at least 75 rounds in the state with no more than a three-year break. At 50, a boxer can claim their pension, which is determined by how many rounds they fought and the size of their purses.

But critics said the commission has not developed an adequate system to inform boxers about their benefits despite years of complaints from lawmakers and state auditors.

Retirement planning experts said a pension plan structured like California’s should mail annual statements as soon as a person is vested. The athletic commission waits until a boxer turns 50 before attempting to contact them for the first time. By then, the vast majority of addresses are no longer current.

The commission said it sent statements last year to Kemp and other boxers interviewed by The Times, but acknowledged that the addresses on file could be decades old.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“That’s a really good way to ensure people don’t get the benefits they are entitled to because by the time you send it you’ve lost contact with them,” said Nari Rhee, director of the UC Berkeley Labor Center’s Retirement Security Program.

The agency’s website includes a link that lists beneficiaries, but until March it was incomplete and replete with misspelled names. The alphabetical list also stopped at last names beginning with “S.” After The Times raised questions, the commission fixed that issue and updated the list.

Three-time world boxing champion Mark “Too Sharp” Johnson thought he wasn’t allowed to apply for his pension yet because his name wasn’t listed when he initially searched the website. He learned from The Times he was eligible beginning last year.

“It’s frustrating,” said Johnson, 51, who is owed a lump sum of $66,000.

Peter Villegas, who joined the athletic commission in 2020 and is now the board’s chair, said that the agency has relied too heavily on promoters and managers to tell boxers about the pension and that “we’re accountable for that.”

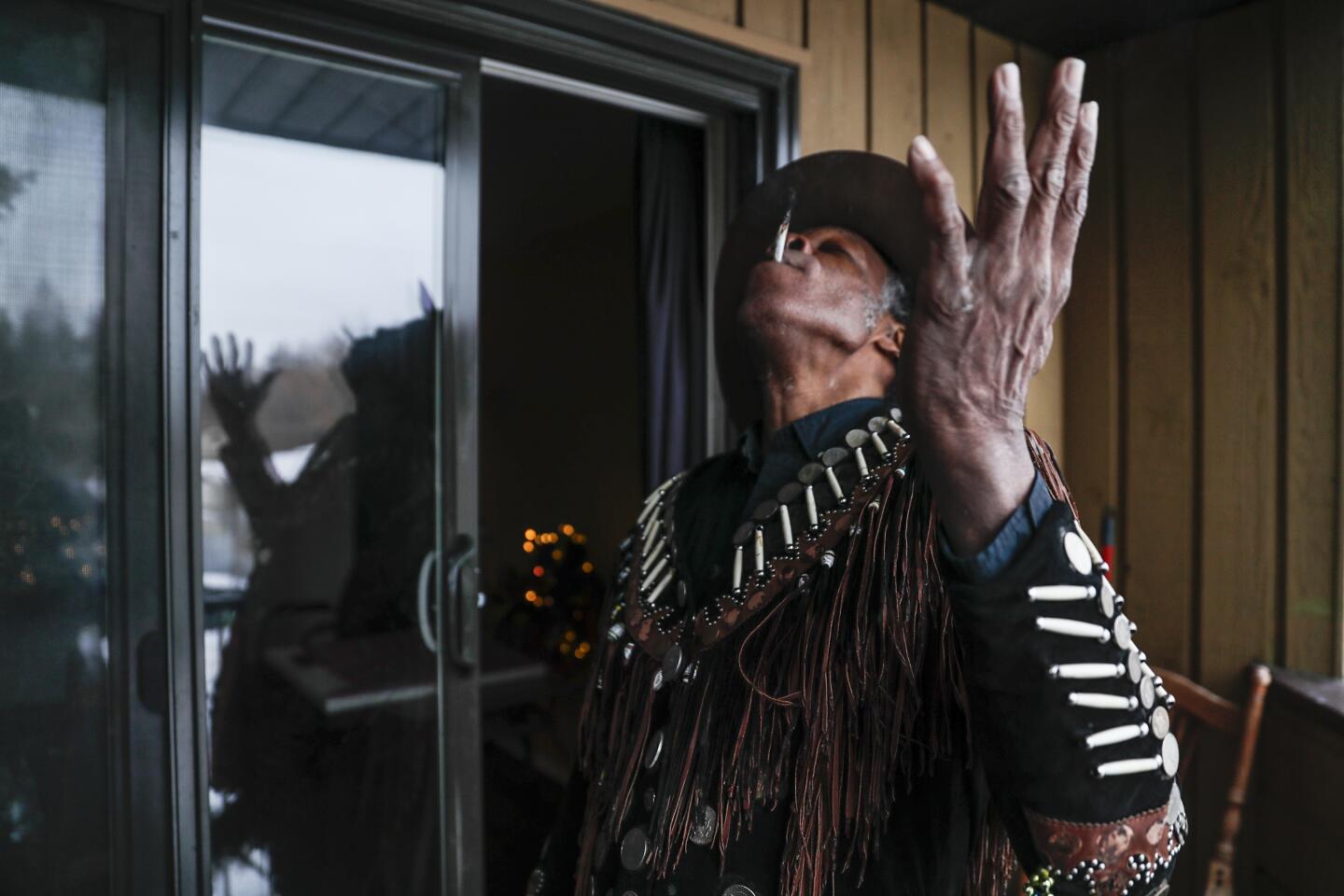

Alex Ramos started a foundation to help struggling boxers after retiring. But he has been unable to tap a California pension program to assist with his own needs.

“Even though we are the only ones doing this, that doesn’t make us experts in this,” Villegas said Monday. “We have to continue to work and do better.”

Andy Foster, the commission’s executive officer, defended the program and its aims while acknowledging its shortcomings, including six years in the 2000s when not a single pension was paid. The regulatory agency is short-staffed, and Foster said there isn’t a “budget for finding people.”

Nevertheless, he is championing proposed legislation to create a pension plan for mixed martial arts, another combat sport regulated by the commission.

“The thing ain’t perfect,” said Foster. “Nobody else is doing nothing. So if we get a C-plus, they get an F.”

It was the taunts of other teens that drove Hector Lizarraga to boxing. At 16, he wasn’t sure where he could learn to fight, but he was certain he needed to master it.

His father had long left and his mother’s death in Mexicali had prompted him to cross the Mexico-California border with his older sister two years earlier. It wasn’t an easy life in America. He didn’t speak English and was adapting to a new high school in Fresno. At the same time, he worked as a laborer picking strawberries and grapes in the Central Valley.

Then came the bullies.

“I thought I needed to learn to fight,” he said. “I thought about wrestling, but it seemed fake, and karate was expensive.”

He found a boxing coach working in the same fields.

“I just fell in love with boxing,” said Lizarraga, who eventually dropped out of high school to make more money working in the fields. But he didn’t give up boxing. He was methodical with his training, studious in the ring. Boxing was more than a whirlwind of punches to Lizarraga.

“It’s like playing chess,” said Lizarraga, whose nickname in the ring was “Papi.”

He left the fields to fight all over the country, winning the IBF featherweight world title during a lengthy 18-year professional career that ended in 2003. But four months after his last fight, his winnings from boxing were running dangerously low. And he realized his future, with little education or work experience, was grim.

He had returned to Fresno, where many people knew him. They called him champ.

“I called a person I knew and said I was looking for a job,” Lizarraga said. “He thought I was kidding.”

The next day, the champ was delivering tortillas.

Hector Lizarraga qualified for the California Professional Boxers’ Pension Plan. It’s the nation’s only state-administered retirement plan for fighters. He’s using the money to invest in his backyard gym.

Lizarraga enrolled at Fresno City College and applied five times for a county job at juvenile hall before landing a full-time position. Taking night classes, he earned his degree and became a police officer in Clovis and then near the California-Mexico border in Imperial. He retired in January, after 21 years in law enforcement, at 56.

“A year ago, I was talking with co-workers and it occurred to me, oh, you know what? The state has something for me in a boxing pension,” Lizarraga recalled in a February interview.

He doesn’t recall ever receiving a statement or any other documentation about the pension, but he had heard about the retirement plan from other boxers. Lizarraga found his name on a list of boxers owed pensions on the athletic commission’s website. He said he assumed the retirement plan would follow the same rule as his other public pension — the longer you wait to apply for the benefits, the more you receive. So he didn’t think he needed to file for it right away.

The boxers’ pension, however, is governed by a set of complex rules that are unlike traditional pensions, which are paid out monthly over a lifetime. Boxers become eligible for their pension when they turn 50 and have three years to claim it. If they fail to do so, most of the money in their account is earmarked for other boxers who have not yet turned 50. The remaining portion is then reserved for those — such as Lizarraga — who claim their pensions late.

The commission’s contracted pension administrator, Benefit Resources, has raised alarms in the past about the impact of too many boxers coming forward with late claims in the same year.

“As they come back and request benefits, we take it from people who are already leaving their benefits behind, and we’re taking from them to pay the people who have come forward,” Benefit Resources’ founder Beth Harrington told the commission in 2019.

Joe Nation, a public policy professor and project director for Pension Tracker at Stanford, said that setup creates uncertainty.

“What happens if every boxer showed up tomorrow and says, ‘I want my money?’” Nation said.

After speaking to The Times, Lizarraga immediately went to work filing for his pension. His first and middle names are reversed in commission records, and Lizarraga said the agency initially told him they had no record of owing him a pension.

California owes benefits to about 200 boxers through the California Professional Boxers’ Pension Fund. How to claim a California boxers’ pension.

Eventually, he reached a staffer who saw the mix-up with his name. He sent over his pension forms in early March and was told it would take up to 45 days to process them. As of this week, had not received his check.

Commission records obtained by The Times show Lizarraga’s pension is $39,000. And he knows exactly where he will spend that money. This month, he opened a boxing gym in his backyard, featuring a covered 12½-by-12½-foot ring and seven boxing bags.

The gym will be geared toward teaching the sport to kids. As a teenager, he could have only dreamed of learning to box using the kind of new equipment he now has throughout his backyard. As a police officer, he thought kids in Imperial County had too little to do and ended up in trouble.

“I see boxing as a way of giving them something productive to do,” said Lizarraga, who was inducted into the California Boxing Hall of Fame in 2015. “I’m planning on using it as a platform to give them goals in life. They don’t have to be professional boxers, but they can learn to exercise, learn work ethic and keep their minds occupied.”

Andy Foster came to the California State Athletic Commission to clean up a mess.

He stepped into the role of executive officer in 2012, just months after the resignation of the previous leader, who’d been censured for mishandling the agency’s finances. The commission was at risk of being insolvent, its budget was thousands of dollars in the hole, and a pending state audit promised more bad news.

The commission, which oversees more combat sports cards than any other state, is funded from gate and television fees for those events, with a smaller percentage of its $1.9-million budget coming from fines and licensing fees paid by fighters, promoters, managers, trainers and others in the sport.

Last year, hundreds of thousands of fans watched 116 boxing, mixed martial arts, kickboxing and Muay Thai events throughout California overseen by the commission, whose governing board is made up of seven members appointed by the governor and Legislature.

While mixed martial arts has surged in popularity, boxing remains the main breadwinner for the commission, accounting for 76% of television tax revenue and 56% of event receipts last year, according to the agency.

Foster, a former professional mixed martial arts fighter and onetime head of the state athletic commission in his home state of Georgia, arrived with a pronounced Southern drawl and orders from the commission’s board to fix the agency’s budget and get more boxers paid their pensions.

“The boxers’ pension fund is financed through ticket sales. What do you think happened during COVID when there were no tickets being sold?”

— Andy Foster, executive officer of the California State Athletic Commission

“That was the priority the commission had at the time and continues to have,” Foster said.

Foster’s passion for combat sports and the safety of its athletes was apparent during several interviews with The Times. He still works out daily and looks like the fighter he was and not the bureaucrat he became.

“I was addicted,” Foster, 44, said of his fighting career, which he ended with a 9-2 professional record. “I would do whatever it took to get back in the cage and get hit in the face.”

Under Foster, the commission’s revenue grew to $2.75 million in 2019. Then the COVID-19 pandemic sent revenue plummeting as fights were temporarily halted and then slowly reintroduced amid new safety protocols. He moved staffers to other agencies to avoid layoffs, leaving five people working at the commission, including himself.

Contributions to the boxers’ pension during the pandemic were equally devastated. Under commission rules, the maximum amount that can be generated for retired boxers at each event is $4,600 from an 88-cent ticket fee.

“The boxers’ pension fund is financed through ticket sales,” Foster said. “What do you think happened during COVID when there were no tickets being sold?”

Commission records show that in 2021, ticket fee revenue for the boxers’ pension fell 50%, to $52,000.

Revenue from ticket fees rebounded last year to $92,000, but the pension’s investments plummeted by nearly 20% to $4.6 million.

Supporters of the pension have long lobbied to increase the 88-cent ticket fee — and the $4,600 cap — to provide the “modicum of financial security” as intended by state statute. The ticket fee has been the only source of revenue other than interest and investment income for the pension since lawmakers overhauled the plan in the 1990s and stopped requiring contributions from boxers.

State auditors said the commission is required by law to increase revenue for the pension based on the consumer price index. The commission concluded in the past that it must create those automatic inflation increases and attempted to pass regulations to do so. However, those efforts stalled and the commission now says it does not believe inflation increases for pension revenue are required by state law.

The only time the commission has raised the ticket fee was in 1999.

“That’s outrageous,” said former state Assemblyman Luis Alejo (D-Salinas), who requested an audit in 2012 of the athletic commission. “The cost of living has increased so much. That needs to be updated.”

Foster said the commission plans to use its own rule-making authority to increase pension revenue from various sources — including by raising the 88-cent ticket fee to $1. But finalizing the action could take more than a year, he said.

California boxing promoter Alex Camponovo said increasing the amount companies like his have to pay will be a tough sell. Camponovo said the boxing industry is still reeling from COVID-19 shutdowns and promoters are already paying high taxes and other fees in California.

“It all adds up in the end,” said Camponova, who runs Thompson Boxing Promotions, a smaller company that is a staple of Southern California boxing.

Camponovo said that boxers need the pension and that he understands the short-staffed commission’s difficult task of locating fighters decades after they leave the ring. Many boxers come from humble beginnings, and “there’s not really an understanding of what a pension means,” he said.

“Very few ask questions about it,” Camponovo said.

Foster said his office has created fliers about the pension that are distributed at weigh-ins and attached to license applications filed by boxers. He has worked with the World Boxing Council to locate retired fighters owed pensions who live in Mexico. Based in Mexico City, the WBC helped the commission pay four boxers a total of $76,000 in 2019 and 2020, according to pension records.

“I’ve been on pretty much every radio show and boxing show there is talking about this thing,” Foster said. “We’ve talked about it and talked about it and talked about it.”

Still, for the vast majority of retired boxers, the onus is on them to learn about their pensions.

The commission has twice been criticized by state auditors for failing to mail annual pension statements once boxers become vested. In 2021, the agency sent statements to 70 of the 465 boxers who had met requirements for a pension, according to the commission. It does not track how many statements are returned to sender.

To locate boxers, a staff member periodically reviews the list of unclaimed pensions to spot names for which there might be an updated email address or phone number. Anything more, Foster said, is beyond what his small staff can do.

The agency also plans to hire a private investigator — using commission funds — to locate boxers with outdated addresses, Foster said. It’s a plan that has been in the works for years and was sidelined during the pandemic.

But, Foster added, “we encourage anybody who is eligible for a pension to contact us.”

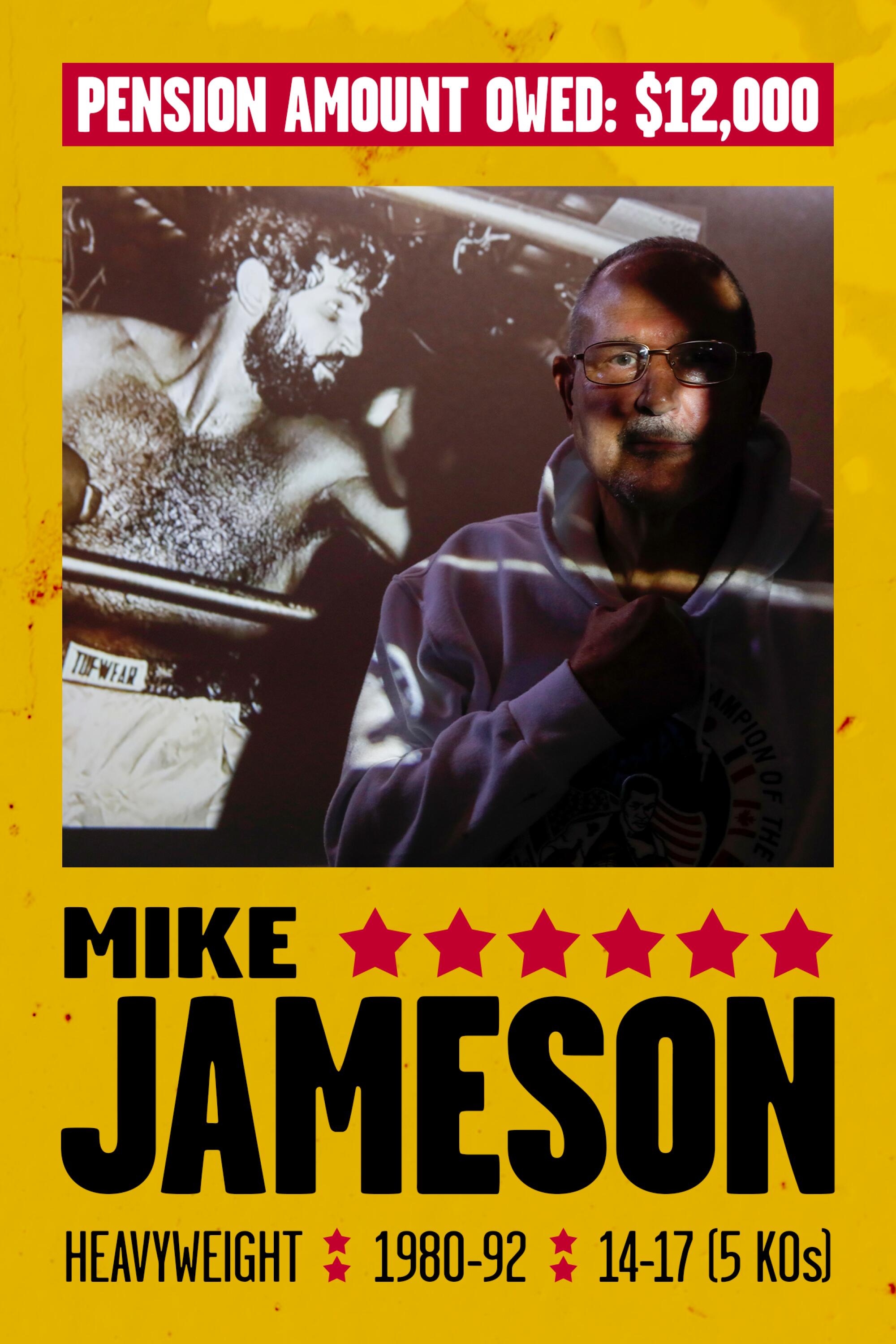

Framed boxing pictures decorate Mike Jameson’s bathroom, his low-lit living room and his cluttered man cave of a garage in San Jose. Yet, he says he hasn’t thought much in recent years about boxing until he heard about the California boxers’ pension earlier this year from a Times reporter — some 18 years after he was supposed to claim it.

“No one ever brought this to my attention,” said Jameson, 68, who went by “Irish Mike” when he fought George Foreman, Mike Tyson and other big-name fighters during his career as a heavyweight journeyman.

“I didn’t know,” he said, before adding, “I’m guessing that’s the point.”

For the last 30 years, he’s lived in the same duplex, which is why he laughs when he’s told the California State Athletic Commission probably doesn’t have an address to send him pension information. It’s the same address he listed after his boxing career ended and he applied for a state license to work in pest control.

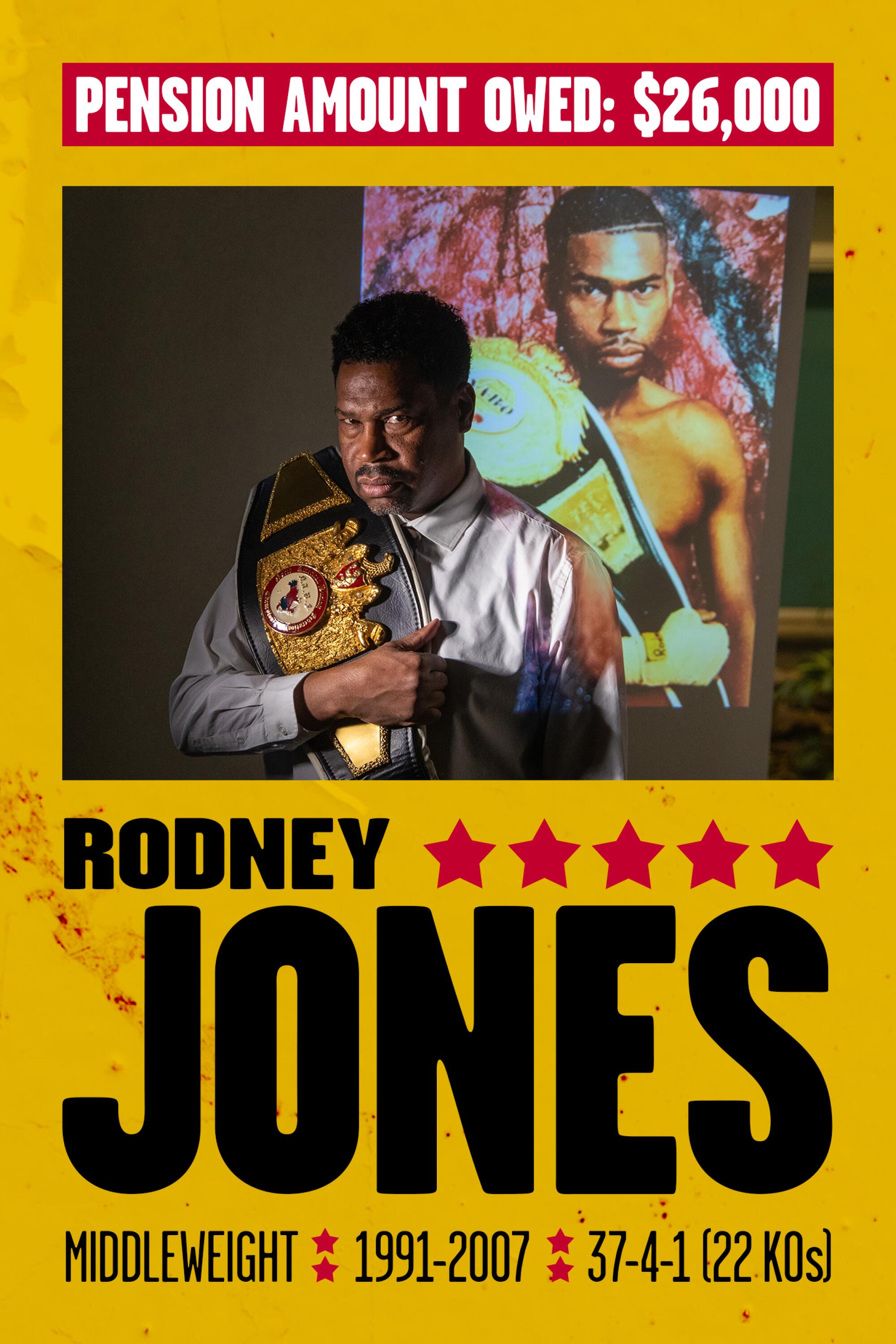

Many boxers also stayed in the cities listed as hometowns in online fighter profiles, making them particularly easy for The Times to locate. That includes Stockton light-middleweight Rodney Jones, 54, who now works as a financial coach in the city where he hung up his gloves. Jones is owed $26,000 from the California boxers’ pension. Other fighters never left California, but said they have yet to receive any information notifying them about their pension.

“This is the first time I’ve ever heard about a California boxing pension,” said Robert Rosiles, 55, a retired boxer from Blythe who now works as a chef in San Diego.

Rosiles fought for four years in a breakneck fashion, logging 28 fights while hopping between Mexico and California before retiring from the sport at 22. He first learned about his $18,000 pension from The Times.

Pension amounts are adjusted annually based on revenue generated from ticket fees and how much is in the plan’s investment account. Boxers receive a share of that money based on the number of rounds fought in California and the purse of each bout.

“Irish Mike” fought George Foreman, Mike Tyson and other big-name fighters during his career as a heavyweight journeyman. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

When a boxer turns 50, that year’s calculation of what they are owed is set, neither increasing nor decreasing regardless of when they claim their pension.

The complex formula rewards successful fighters, including those who fight for multimillion-dollar purses, but the commission said it balances that with ensuring boxers who toil on the undercard receive their fair share. Last year, that included “Sugar” Shane Mosley, a powerhouse fighter from Pomona with world title belts in three weight classes. Mosley’s pension payout was $203,000, the largest paid by the commission, according to records obtained through the Public Records Act.

For the 11 other boxers paid their pensions last year, the average one-time benefit was $17,400.

It’s not just boxers who are eligible to claim a pension. Spouses and other beneficiaries can apply if a boxer has died. But few have, with just 10 beneficiaries ever having been paid a pension on behalf of a boxer who died, according to commission data.

Norman Stein, acting legal director for the nonprofit consumer group Pension Rights Center, said he’s “never seen anything quite like” the way the boxers’ pension is structured.

“I think the biggest issue is what are they doing to locate people,” Stein said. “And why haven’t they done more?”

In the early years of the plan, unclaimed pensions were allowed to accrue interest and grow over time. But the commission determined in 2013 that was not what the plan rules intended. It then retroactively deducted the accrued interest from the accounts of dozens of boxers who hadn’t yet claimed their pension, many of whom said they were never told they had a pension in the first place.

In Jameson’s case, commission records show his balance was $21,500 in 2012 and is now less than $12,000. Those who claimed their pension before the commission’s change received the higher amount, records show.

Jameson said it reminded him a bit of his disappearing boxing paychecks. He may have made $50,000 to fight Foreman, but after paying his manager, trainer and taxes, he said his take-home was $14,500.

“For me, it was about the journey,” Jameson said. “I got to go to all these cool places. Yeah, I got my tail whipped a whole bunch, but I’m not a rocket scientist.”

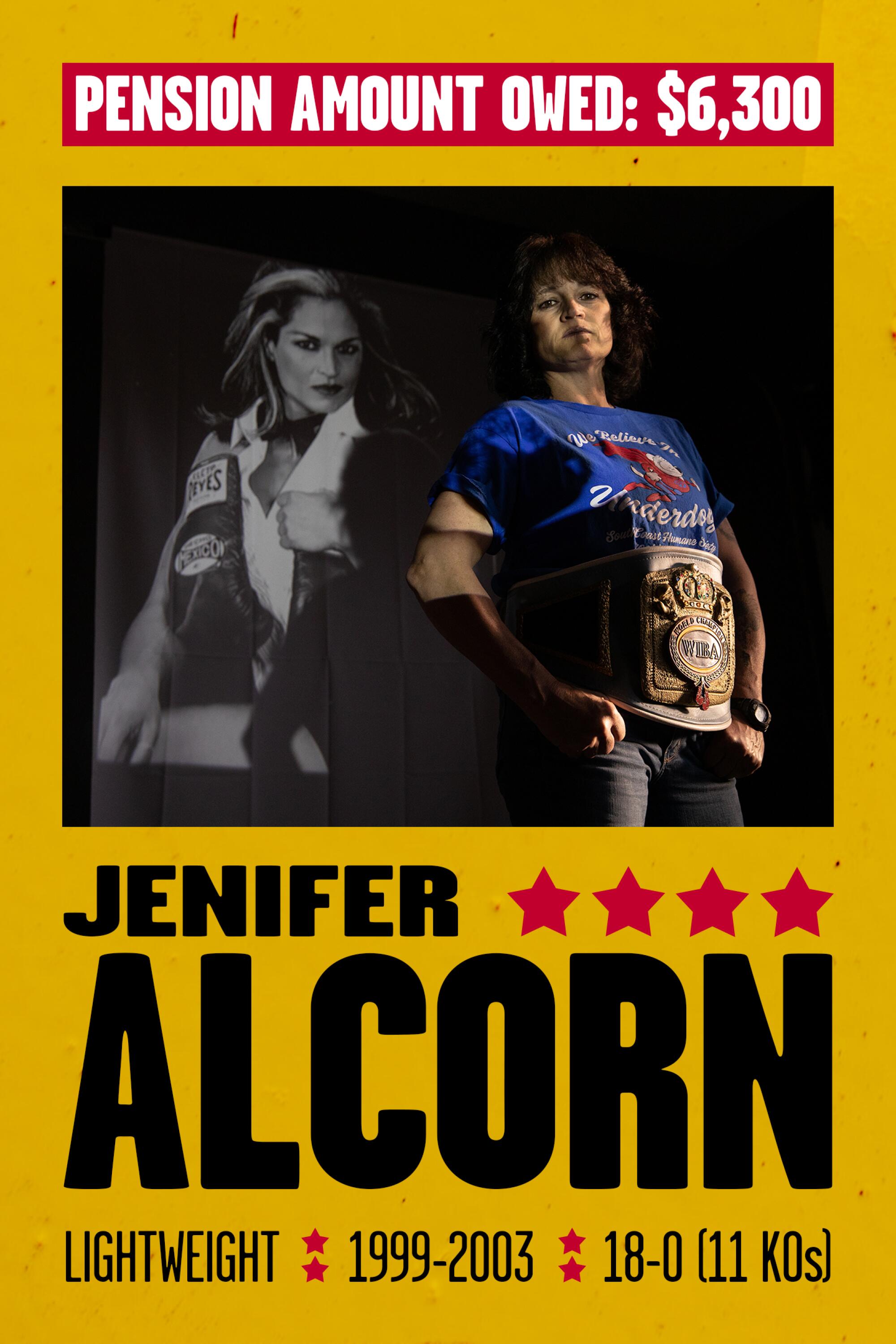

Fresno lightweight Jenifer Alcorn couldn’t contain the curse word that slipped into her surprised reaction in learning from a Times reporter that she had a boxers’ pension.

But elation quickly turned to cynicism. Why had no one told her? Alcorn knows she’s not hard to find. She stayed put for many years after her boxing career ended, building a successful fitness business and teaching the sport to Fresno State athletes as a way to increase mental toughness and focus. Alcorn moved to Oregon six years ago with her husband, never having heard about the boxers’ pension. She’s among the few women owed benefits.

“Quite honestly, it’s very easy to track people down these days,” said Alcorn, 52, who now works as the executive director of South Coast Humane Society in Brookings, Ore., where she has a robust social media presence.

Alcorn found boxing late, turning pro at 27. Her husband, who was in law enforcement, doubled as her trainer, and in between raising a family they worked in the ring. Alcorn was a three-time world lightweight champion, undefeated in her 18 bouts.

“When my kids started participating in athletics, I knew it was time for me to step out,” she said.

She said she sees the benefit of offering pensions to boxers, many of whom come from tough backgrounds. But, she added, telling boxers about it should be a key tenet.

“I don’t count on this money to make my life better, but it’s a nice thing to be able to add to the bank account for my grandchildren,” said Alcorn, whose pension is $6,300, commission records show.

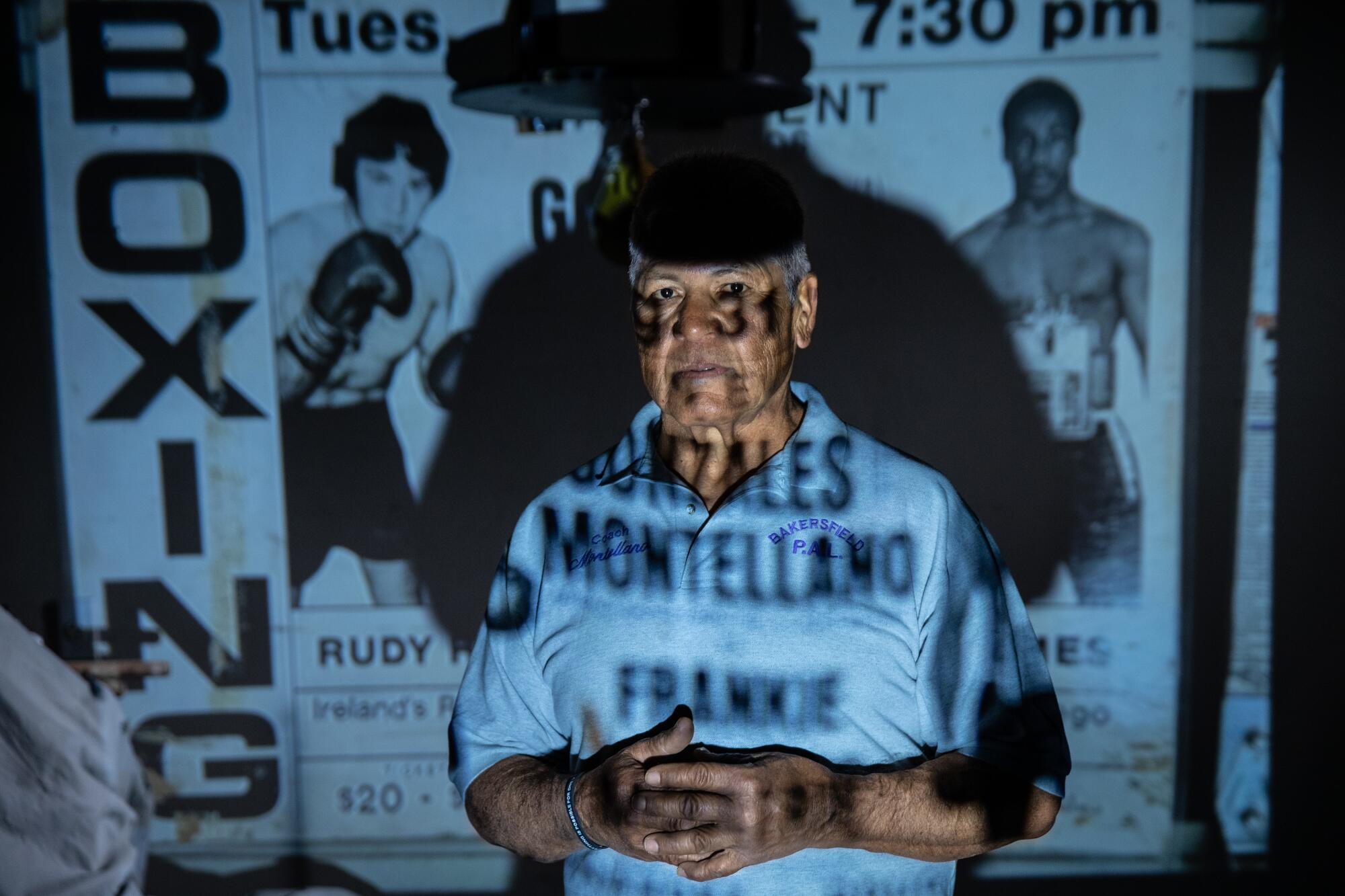

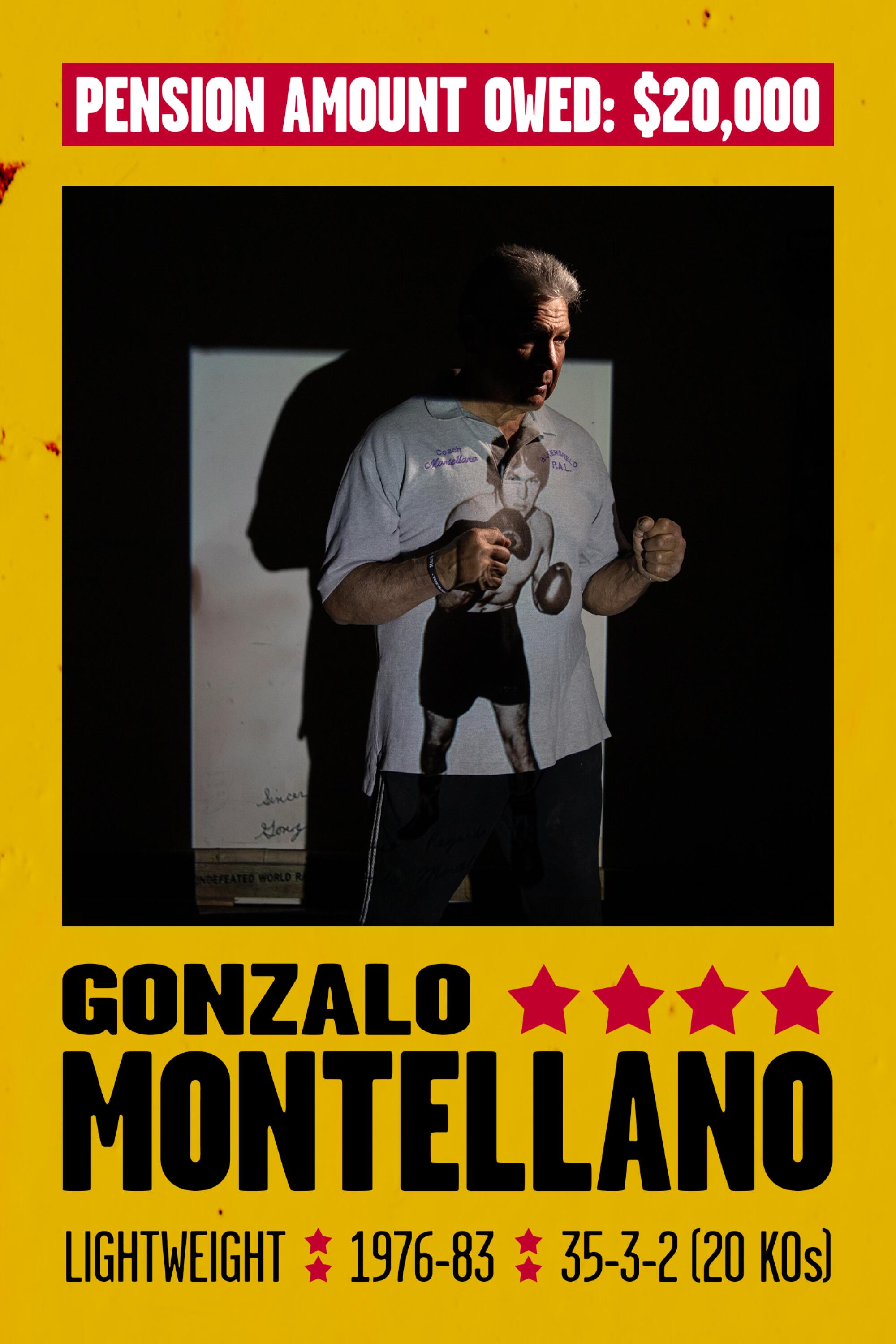

Bakersfield lightweight Gonzalo Montellano remembers the talk about a California pension for boxers, but thought it was started after his eight-year career ended, if at all. He assumed if he qualified, the state would have told him. He had always felt unlucky, despite finishing his pro career with a 35-3-2 record.

For him, missing out on the boxers’ pension was another bad break, one that fell somewhere between a draw in a fight he knew he won and his first manager ending up murdered in the trunk of a Rolls-Royce in 1979.

“I had an interesting, rough career,” Montellano said. “If I didn’t have bad luck, I would have no luck.”

He left boxing in 1983 with little more than anger at the sport that promised him the world when he was fighting at 135 pounds.

“It’s the would’ve, could’ve, should’ve that get you,” Montellano, 65, said. “I felt I got ripped off on a couple of fights that could have turned the entire tide of my career. I stopped fighting and started eating and drinking.”

He said his life got back on track the less he thought about boxing. He’ll help young fighters learn to box, but he won’t train them to compete, saying he’s “still bitter at the sport.” He worked laying asphalt for a while before a friend helped him into a career as a heavy equipment operator.

He logs 10-hour days working for a contractor on the high-speed rail project. The nearly $20,000 in newly discovered retirement money could allow him to cut back his hours, he said.

“I was going to work one more year; now I might not,” he said.

On a rainy March morning in Sacramento, state lawmakers put down their phones and glazed expressions to hear the final bill of the morning — AB 1136 by Assemblymember Matt Haney (D-San Francisco), which would allow the athletic commission to create a pension for mixed martial arts fighters. It’s modeled after the boxers’ plan. Lawmakers didn’t discuss that plan’s shortcomings.

Supporters of the pension for mixed martial artists included retired MMA featherweight champion Urijah Faber and athletic commission board member AnnMaria De Mars, the first American to win the world judo championships and the mother of well-known fighter Ronda Rousey.

“Licensed professional MMA fighters,” Haney told the committee, are “vulnerable to financial insecurity, especially as hospital bills for their injuries continue to affect them post-retirement.”

The vote in the business and professions committee was 17 to 0 in favor. In April, it unanimously sailed through two more committees. It’s now awaiting a vote in the full Assembly, which could come as early as Monday.

It was far different from the struggle supporters of the boxers’ pension faced decades ago in the Legislature. A bill in 1971 authorizing the commission to adopt regulations to create the pension prompted a warning from the state Department of Finance that it was of “questionable value and sets a dangerous precedent,” according to records in the California State Archives.

After the pension was established, the late Assemblymember Richard Floyd, a Democrat from Carson, called it a “rip-off” and introduced a bill that would have given boxers a choice in whether to participate. A 1991 audit requested by Floyd cited poor financial accounting at the commission, which contributed to the agency’s failure to notice when a Department of Consumer Affairs employee embezzled $14,000 in pension funds.

State audits in 2005 and 2013 cited haphazard record keeping and the commission’s failure to locate boxers.

Bob Fellmeth, the architect of the boxers’ pension when he was chair of the athletic commission in 1981, said it has been difficult to see the pension, which has been overhauled over the years, fall short of its mission.

He’s pushed the agency for more accountability of administrative costs paid with pension funds and assailed legislative efforts he said would undermine the program. The commission is failing boxers by not increasing revenue so pensions don’t depreciate over time, said Fellmeth, who is now executive director of the University of San Diego’s Center for Public Interest Law.

Fellmeth said if the boxers’ pension was working as originally intended, retired fighters would be receiving a modest retirement amount that could help pay rent for a few years or other expenses.

“This is one of the things in my life — and I have a 46-page resume — that I am most proud of because no one was doing it,” Fellmeth said. “And if they are screwing it up ... then that’s shameful.”

It’s been decades since Kemp, the “Ballet Boxer,” stepped into the ring. He feels the ache of old injuries and can pinpoint whose fist is responsible.

Kemp had little money when he retired from boxing — his biggest purse for a fight was $2,500. Promising ventures in fashion and art sputtered. For a while, he became a local attraction in Montreal as a Jimi Hendrix street performer. It too never yielded much money.

He’s excited about the prospect that he has $8,800 in the California boxers’ pension, and said if he ever sees the money he may use it for a warm vacation away from his government-subsidized apartment in Edmonton.

In his living room, rickety tables hoist the ornate art he’s built from dollar-store crafting supplies. He’d like to put on an art exhibition to showcase his colorful creations — which incorporate geometric principles that infuse ballet and boxing. He used to paint, but he said his vision was never the same after leaving the ring.

“My eyes now are terrible,” said Kemp, who still has his lean and muscular boxer’s build at 69. “I paid the price. I don’t resent it or anything like that. I don’t feel bitter about it.”

But, he doesn’t watch boxing anymore. Years ago, when he caught a match on TV, he said he found himself sobbing with each punch. He knows what those blows feel like long after the bruises and cuts heal.

And that’s what makes his newly discovered boxers’ pension special, Kemp said. All these years later, the sport that took so much has something left to give him.

Times staff writer Dylan Hernandez contributed to this story

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.