California’s LGBTQ community feeling ignored, angry, confused as monkeypox cases rise

Antonio Palacios recovered from COVID-19 in early June, just in time for back-to-back weekends at Southern California’s largest Pride celebrations — in West Hollywood and Los Angeles — where he immersed himself in a community that, at times over the last two years, felt distant.

“We needed to be together. We needed to have that release,” said Palacios, who is gay.

But soon after, Palacios got a call from a man he recently started dating, informing him that he had likely been exposed to monkeypox, the rare virus recently confirmed in California and spreading almost exclusively among gay and bisexual men and transgender and nonbinary people.

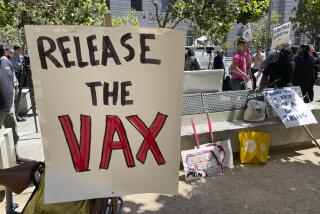

LGBTQ activists and health leaders have been sounding the alarm about monkeypox for weeks, saying they were inadequately prepared and overlooked by public health officials. Now, many state and local officials are joining the call for a better response to the outbreak — especially, efforts to get more vaccines.

“Had federal officials shown a strong will to action, more could have been done to stop the spread just using basic public health,” California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) said Wednesday, calling on federal officials to declare monkeypox a national public health emergency. “During recent Pride Month activities, thousands of those vaccine doses could have been administered at celebratory events, clinics, LGBTQ bars and gathering places throughout the state. That did not happen, and it enabled the spread.”

Although the monkeypox virus can affect anyone, some gay and bisexual men are worried about being once again branded as carriers of an exotic disease.

Monkeypox cases in Los Angeles and San Francisco counties have continued to rise since late June — increases that coincided with Pride weekends. Advocates say efforts to provide preventative and post-exposure protection to those most at risk are hampered by severely limited availability of vaccines.

When cases began appearing last month in Los Angeles County, only about 1,000 vaccine doses from the federal government had arrived, a shortage Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer called “distressing.” Many of those infected had been linked to two large parties.

About 24,000 doses have now made their way to L.A. County. The additions are welcome improvements but far short of what is needed to adequately respond to the virus, experts say. Dr. Mark Ghaly, the California Health and Human Services secretary, wrote to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Wednesday requesting an additional 600,000 doses — more than 15 times what the state has already received. Ghaly’s agency, which distributes vaccines to all California counties besides Los Angeles, had received fewer than 38,000 doses as of Thursday.

Officials say they don’t expect the shortage to be resolved for months.

Monkeypox, which is rarely fatal but can cause severe pain and uncomfortable symptoms for as long as a month, had been confirmed or considered probable in 223 people in Los Angeles County as of Monday, more than double the number from a week prior, according to the Department of Public Health. The rise has been similarly fast in San Francisco, reaching 215 cases Monday, up 50% from the week before. The two metro areas account for two-thirds of California’s confirmed or probable cases.

“This should be a preventable public health crisis,” San Francisco City Supervisor Rafael Mandelman said this month. “Unlike COVID-19, we did not have to wait for a vaccine to be developed. And unlike COVID-19, monkeypox does not seem to spread effectively through respiratory droplets. Yet here we are with cases rising, vaccines sparse and urgent action by our federal public health institutions absent.

“Would monkeypox have received a stronger response if it were not primarily affecting queer folks?” he asked.

Gay, bisexual and transgender communities fear a repeat of the AIDS-era indifference that left too many without care.

Palacios lamented the lack of available treatment, cumbersome protocols and slow response from public health officials in combating the virus, which spreads primarily through intimate skin-to-skin contact.

“After a million COVID deaths in the U.S. … how could we be caught flat-footed again?” Palacios asked. “Rather than rolling out treatments, they’ve just put gay men on house arrest. ... If we’re the only people that seem to be suffering from something, then the powers that be don’t seem very inclined to reach a positive solution.”

Palacios — who was among the first 30 confirmed monkeypox cases in L.A. County — has recovered from a relatively mild bout. But the Public Health Department did little to help, he said. During the first few days he experienced symptoms, he repeatedly called for assistance, he said; at one point, he was directed to speak with a veterinarian, who gave him advice for protecting his dog from the virus.

“Every day that was ticking by felt critical,” the 41-year-old West Hollywood resident said.

He asked county health officials about getting the monkeypox vaccine when he was within the 14-day exposure window, as recommended by the CDC, as well as an antiviral treatment approved in Europe. The Jynneos vaccine, the primary option in the U.S., is a two-shot series given four weeks apart; full protection is considered to be reached two weeks after the second dose, according to the CDC.

But the L.A. County Department of Public Health does do not administer vaccines to anyone who is already infectious, because the vaccine “will no longer provide benefit,” officials said.

“We appreciate and share the frustrations of the community,” the agency said in a statement. The county is working to provide vaccines to the “highest-risk population,” as well as treatment for those “where it is clinically indicated.”

The San Francisco AIDS Foundation said its vaccine wait list — comprising people with a known exposure to monkeypox — is up to 6,500. The organization’s health clinic has received about 1,000 doses.

“We would need something like 6,000 doses to treat our sexual health clinic folks who may be at risk for monkeypox,” Tyler TerMeer, chief executive of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, said last week.

That’s close to the number of doses the entire city has received since the outbreak began. San Francisco’s Department of Public Health last week requested 35,000 doses; days later, just 4,000 were provided.

“Are we in another moment when the lives of gay and bi men are not being prioritized?” TerMeer asked, alluding to the HIV and AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s. “There needs to be more urgency.”

Federal officials have ordered millions more doses, but manufacturing challenges make it unlikely that the vaccines will be available soon. The World Health Organization this weekend declared monkeypox a global health emergency, a designation that will ensure it is taken seriously, medical leaders hope.

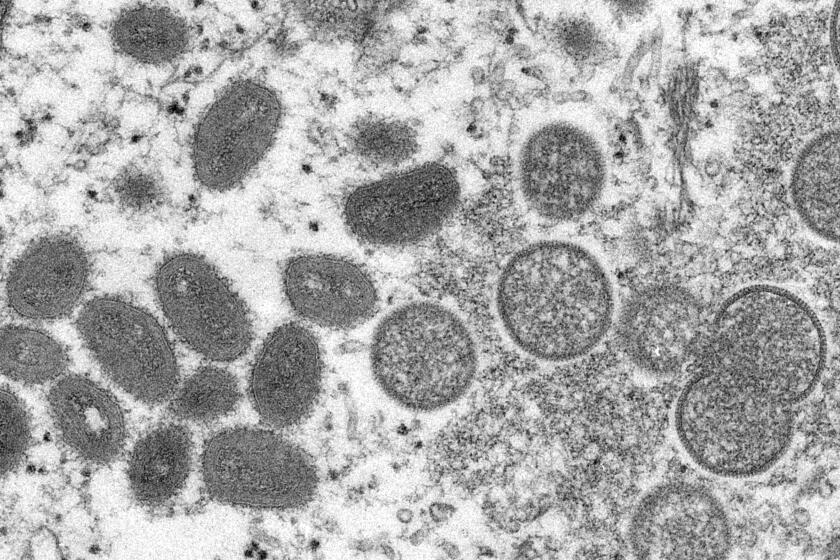

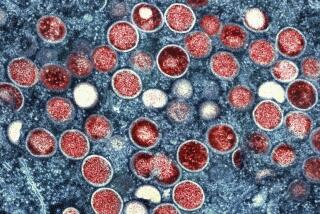

Monkeypox is garnering increased attention because outbreaks and cases are showing up in areas where they don’t usually occur.

Scott, who asked to be identified only by his first name because he’s a sex worker, said he tried to protect himself before traveling in late June to New York City’s Pride celebrations but was told by multiple health providers that he wasn’t eligible for the monkeypox vaccine.

The government has “known about this since May, and they knew it was primarily [affecting] men having sex with men — and there was no coordinated response going into Pride Month,” said Scott, who later tested positive.

“The government isn’t going to take it seriously until straight people start getting it,” he said. “Thankfully, it’s nothing like AIDS, but it feels like the government response has failed in the same way with AIDS, or with COVID.”

Everything you need to know about monkeypox.

Although the LGBTQ community has been disproportionately hit by monkeypox, officials warn that anyone can become infected. While primarily transmitted skin-to-skin, it also can be spread through materials that come into contact with the virus, such as bedding and towels, or through close contact with respiratory droplets, such as can occur while kissing.

Health centers that provide care to predominately queer clients say they are bracing for many more months of an all-hands-on-deck response as the virus continues to spread.

TerMeer said that after San Francisco Pride, the AIDS Foundation began receiving an influx of “concerned and fearful” callers. The organization set up a monkeypox hotline, which has been getting more than 500 callers a day since early July.

Ward Carpenter, director of health services for the L.A. LGBT Center, said the spreading virus is “definitely starting to strain our resources.”

“We’re sending more and more [tests]. We’re increasing staffing to be able to serve as many as we can,” he said. “From everything we’re seeing, we’re on the uphill curve here.”

Scott, who lives in West Hollywood, said it was almost a week after he tested positive before he heard from L.A. County, but a health official offered no treatment options and inquired only about contact tracing, while insisting that he stay at home.

“They were not interested in my health. They were not interested in providing options for treatment,” Scott said, noting that contact tracing almost 11 days after his symptoms began seemed “laughable.”

He was particularly upset knowing that much of Europe has access to an antiviral treatment known as Tpoxx — the same one Palacios wanted — but it’s allowed in the U.S. only under limited “investigational” circumstances, according to the CDC, for people with “severe disease” from monkeypox.

“We understand it can feel like a long time to patients after they first hear they may have been exposed, and we have been working to improve the situation as fast as we can,” the L.A. County Public Health Department said in a statement. The agency said it has been working to speed up the testing process, with help from commercial facilities, and is working to streamline the process for providers to prescribe Tpoxx — though federal guidelines limit its use for patients with complications or those at high risk.

“Most patients will get better without treatment,” health officials said. “Our records indicate we have reached out to persons with positive results within 24 hours of hearing about a positive result. We understand this might have felt differently ... because ... patient anxiety starts as soon as they hear about an exposure. But we cannot ... begin case interviews until we receive the result.”

Rick Chavez Zbur, an LGBTQ civil rights leader and former executive director of Equality California, said there needs to be enough Jynneos doses to vaccinate all at-risk gay and bisexual men, as well as transgender and nonbinary people.

“It is not an acceptable public health strategy to have members of the LGBTQ+ community put our lives on hold while we wait for insufficient supplies of vaccines to dribble out,” Zbur said. “Every day that vaccines are widely unavailable relegates gay and bi men and transgender people to living lives of fear and isolation, reminiscent to the early period of both the HIV and COVID epidemics.”

Some in the LGBTQ community are worried that the vaccine shortage will allow for spread of monkeypox.

At one of Long Beach’s final Pride events, on July 10, monkeypox seemed a far-off concern for most. Attendees donned rainbow clothing, waved LGBTQ flags and packed the city’s gay bars.

“People are so excited to be together again. You can feel the energy,” parade emcee Cory Allen said. “There’s a level of consciousness” about monkeypox, he said, but his social and professional circles were not alarmed.

Raul Victoriano, 42, who was sporting not much more than a rainbow Speedo, admitted that “people are letting their guard down” but said it was equally important to come out to support the queer community.

“I thought about [monkeypox] coming out here,” said Victoriano, who is gay. But he said he wasn’t too worried because he wouldn’t be going into crowded clubs. He did, however, plan to contact his doctor to try to get the vaccine.

“The future is scary, but we’re out here celebrating love. We’re here, and we’re loud,” said Fabián Bon, who was at the Pride parade with his fiance. Monkeypox “is another thing ... to be mindful of.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.