Monkeypox: Why L.A. is watching out for this rare but potentially serious illness

An increase in the number of cases of monkeypox, a rare but potentially serious viral illness, in Europe and a single case in Massachusetts is attracting increased attention from health officials.

While monkeypox is in the same family of viruses as smallpox, it has been nowhere nearly as contagious as its better known cousin, nor is it anywhere nearly as contagious as the virus that causes COVID-19.

Monkeypox is garnering increased attention because outbreaks and cases are showing up in areas where they don’t usually occur, raising questions about whether there’s an increased chance for human-to-human transmission.

There are no known cases of monkeypox in Los Angeles County, Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said. “We do want to reassure people, it’s really, really rare,” Ferrer said.

But the county is monitoring for monkeypox cases, and will be issuing guidance to healthcare providers so they can report suspected monkeypox cases to the county. People should contact their healthcare providers if they notice an unusual rash or skin lesions that “generally start in one area, but pretty quickly spread over the body,” Ferrer said.

New York City is investigating a possible case of monkeypox, city health officials said.

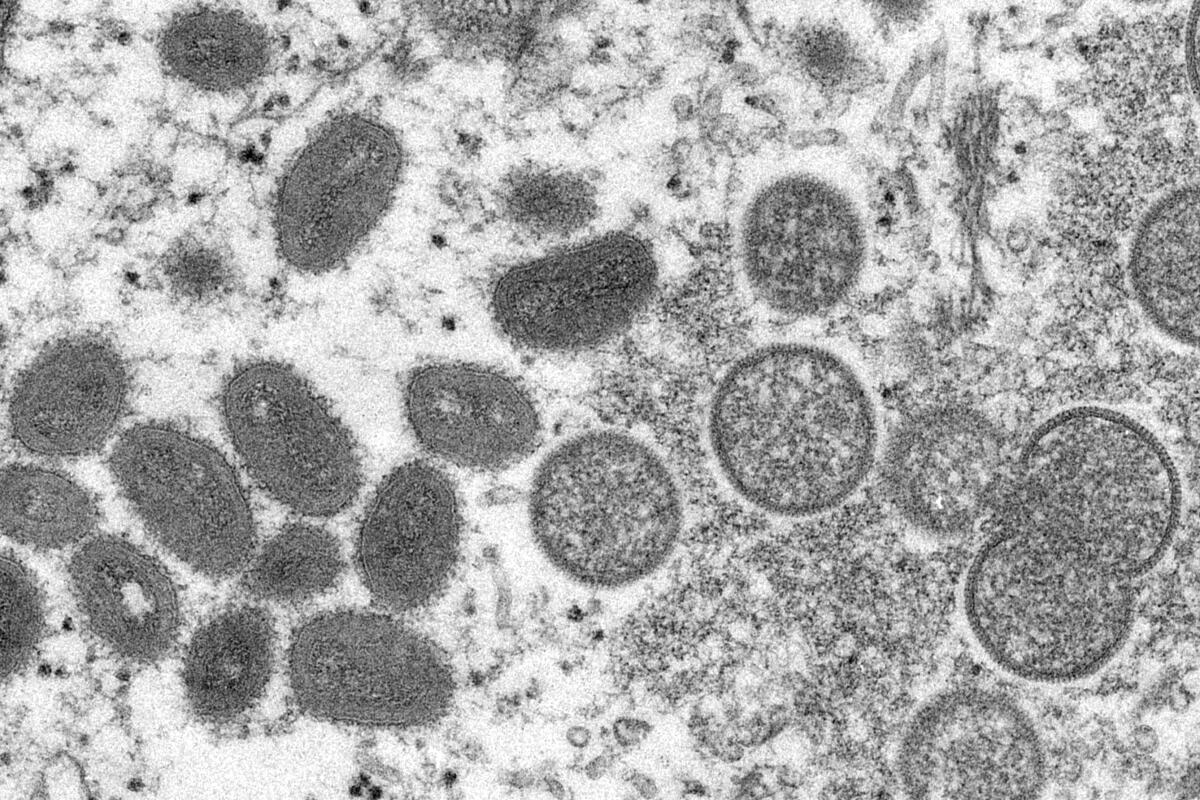

Monkeypox causes symptoms similar to smallpox, but they are generally milder. The illness begins with fever, aches, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion, and then later develops into a rash, usually starting on the face and then spreading to other parts of the bodies, turning into pus-filled sores before they fall off.

The illness can last two to four weeks. According to the World Health Organization, historically, between 0% and 11% of those with monkeypox infections have died from the disease, with the fatality rate higher among younger children.

The last major monkeypox outbreak in the U.S. occurred in 2003, leading to 71 confirmed or suspected cases — mostly in Wisconsin, Indiana and Illinois. The confirmed cases had contact with pet prairie dogs obtained from an animal distributor in suburban Chicago that had been housed near Gambian giant rats and dormice that came from Ghana.

No one died in this U.S. outbreak. Only two patients — both children — had serious illness; both recovered.

The 2003 outbreak was the first time monkeypox had been detected in the U.S.

It usually takes seven to 14 days after exposure for the onset of symptoms, but it can take as long as 21 days before symptoms appear.

There are tools available to control monkeypox outbreaks, the CDC said, including use of the smallpox vaccine, which is not available to the general public. One vaccine has been licensed for use in the U.S. to prevent monkeypox and smallpox. “Past data from Africa suggests that smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox,” the CDC said.

“In the event of another outbreak of monkeypox in the U.S., CDC will establish guidelines explaining who should be vaccinated,” the CDC said. Smallpox is the only infectious disease that targets humans that has been declared eradicated.

People are usually exposed to the monkeypox virus through bites or scratches from infected animals, Ferrer said.

“But while it doesn’t spread easily between people, it can spread through contact with bodily fluids,” Ferrer said. The virus can spread through contact with the monkeypox sores, through items — like clothing and bedding — contaminated with fluids or with the sores, or through respiratory droplets following prolonged face-to-face contact.

Common household disinfectants can kill the monkeypox virus, Ferrer said.

Monkeypox, first discovered in 1958 in colonies of monkeys kept for scientific research, is typically found in rodents and primates in central and western Africa, the CDC said.

The first human case of monkeypox was found in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970.

The European outbreaks have attracted enough attention that the CDC is assisting with the investigations of the European monkeypox cases.

Recent cases of monkeypox in humans have been reported in Portugal, Spain, Britain, Italy and Sweden, according to the Associated Press. A single case this week was reported in Massachusetts, in which the infected man recently traveled from Canada. The person took private transportation between Canada and Massachusetts, the CDC said. Officials in Montreal are investigating suspected infections, the AP said.

“It’s not clear how people in those clusters were exposed to monkeypox, but cases include people who self-identify as men who have sex with men,” the CDC said on its website. “CDC is urging healthcare providers in the U.S. to be alert for patients who have rash illnesses consistent with monkeypox, regardless of whether they have travel or specific risk factors for monkeypox and regardless of gender or sexual orientation.”

“Many of these global reports of monkeypox cases are occurring within sexual networks. However, healthcare providers should be alert to any rash that has features typical of monkeypox. We’re asking the public to contact their healthcare provider if they have a new rash and are concerned about monkeypox,” Dr. Inger Damon, a poxvirus expert and director of the CDC’s Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, said in a statement.

There were a couple of monkeypox cases recorded in the U.S. in 2021.

In November, CDC and Maryland officials confirmed a monkeypox case in a U.S. resident who had traveled to Nigeria.

And last July, a case was confirmed by CDC and Texas health officials in a U.S. citizen who had traveled to Nigeria; officials identified more than 200 people who had possible contact with the person. No additional cases were found tied to the traveler.

The CDC said monkeypox reemerged in Nigeria in 2017, following more than 40 years with no reported cases in Africa’s most populous nation. There have been more than 450 reported cases in Nigeria; at least eight cases have been exported globally, the CDC said.

Studies on monkeypox were limited starting in the mid-1980s, and data collection efforts faded for a couple of decades. Data collected between 1981 and 1986 suggested that “monkeypox virus was highly unlikely to sustain itself in human populations and, therefore, did not constitute a major public health problem,” according to a research article on the subject. Smallpox vaccination efforts ended in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1980, around the time smallpox had been declared to be eradicated.

Then, in 2010, a study was published showing the results of more recent disease surveillance in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The study suggested a twentyfold increase in the incidence of human monkeypox between the early 1980s and between November 2005 and November 2007.

“Thirty years after mass smallpox vaccination campaigns ceased, human monkeypox incidence has dramatically increased in rural [Democratic Republic of Congo],” said the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and authored by 19 scientists. The lead author of the report is Anne Rimoin, professor of epidemiology at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

A driver in monkeypox virus infection in Africa is contact with animals that are infected, the study said.

“Monkeypox continues to occur almost exclusively in rural villages located in or near the tropical rainforest. Degraded secondary forests and semi-deciduous forests with many oil-palm trees, two habitats associated with monkeypox risk, are often found near these villages,” the report said. “Continued clearing of forest from logging or to open new land for agriculture may favor an increase in human exposure to squirrels and other suspected reservoir species, providing increased opportunities for zoonotic transmission of monkeypox.”

“Additionally, recurrent civil war and collateral increase of poverty has forced residents to rely more extensively on locally available sources of protein, such as monkeys, squirrels, and other rodents for sustenance—all of which are potential sources of human infection,” the report said.

There are reasons to think human-to-human transmission of monkeypox has increased, the report said.

“Declining vaccine coverage has the potential to cause additional nonlinear increases in human-human transmission. Entire households are now mostly or completely vaccine naïve, as compared with the 1980s, when only small children were susceptible,” the report said.

The scientists warned that human monkeypox could someday become a “global health concern,” such as if monkeypox became established in a wildlife reservoir outside of Africa, like among American ground squirrels, who are susceptible to the monkeypox virus.

“If monkeypox were to become established in a wildlife reservoir outside Africa, the public health setback would be difficult to reverse,” the report said.

“The possibility that rising incidence may reflect increased human-to-human transmission raises further health concerns and should be studied because greater circulation among humans opens the possibility of geographic spread by travelers, prompting analogies to the international spread of SARS or the pandemic influenza of 2009.”

One trait of monkeypox — its distinctive symptoms — would, however, help officials contain its spread.

The scientists urged that more be done to reduce human monkeypox infection.

“Failure to pursue a more comprehensive assessment of epidemiology, risk, and possible control measures could have serious implications,” the scientists wrote. “Inaction ignores the preventable morbidity suffered by indigenous populations, in the worst case risking increased adaptation of monkeypox to humans and potentially resulting in a lost opportunity to combat this infection while its geographic range is still limited.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.