LAUSD’s slow, cautious reopening shows the influence of the teachers union, but it has critics

The Los Angeles school district is set to unfold a gradual and partial reopening plan on Tuesday, one that was heavily influenced by teachers union demands that led to a delayed start date and limited live instructional time — and also by strict safety imperatives shared by both the district and union.

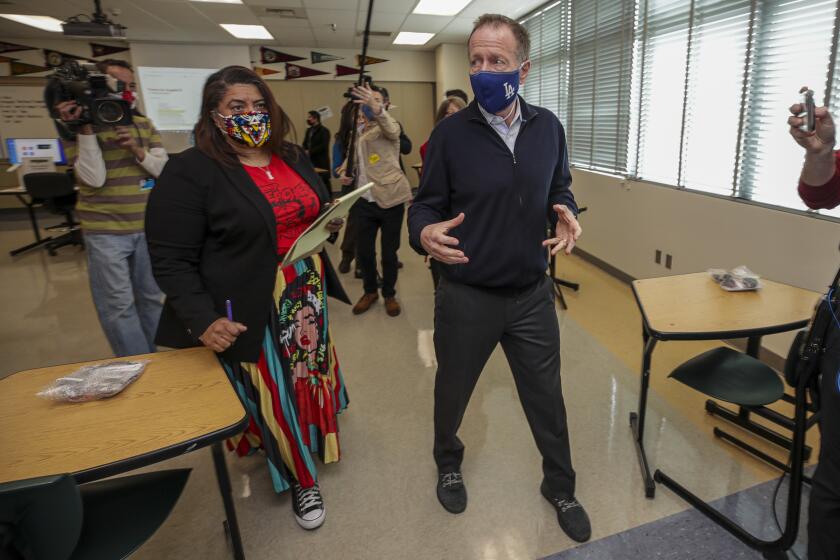

L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner has hailed the reopening as a nation-leading model for school safety that is sensitive to families in low-income communities hardest hit by illness and death during the pandemic. But the approach has also generated criticism from those who say the quantity and quality of instruction for 465,000 students have been sacrificed this year as a result of union concerns.

The key safety provisions — including mandatory coronavirus testing for students and staff as well as six-foot distancing between desks — go beyond what health authorities require. The distancing policy has resulted in a half-time on-campus classroom schedule. The timing of reopening — about two months after elementary campuses were eligible to reopen — was set to allow teachers and other district staff to achieve maximum vaccine immunity.

These decisions have defenders, including many parents who live in neighborhoods devastated by COVID-19 and who are still undecided about whether it is safe enough to send their children back to school. But the choices of Beutner and the school board have come with tradeoffs.

“LAUSD’s plans for reopening continue to limit access to in-person learning in ways that fall far short of what many other school districts across the state, including Long Beach, are providing,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of USC Rossier School of Education.

The format launching Tuesday provides two options for parents: a half-time learning schedule on campus that still includes remote instruction or a remote-only option. Based on survey results, about 39% of elementary school students will be returning, 25% for middle schools and 17% for high schools.

The deal is good news for working parents of elementary school children, who can remain on campus all day. Union members will vote next week.

It could turn out that the emphasis on safety will pay off in building confidence among wary parents and families who have endured deadly coronavirus surges — some favor a phased-in return while other are not yet ready to send their children back under any circumstances. Moreover, the union agreements have avoided the labor acrimony that has played out at times in other cities, including New York City and Chicago.

However, other parents have become impatient, blaming the district or union or both, for the education deficits and harms of isolation suffered by their children. This discontent has surfaced in three lawsuits against the district — two of them also name the union as a defendant. All target various aspects of the district’s pandemic learning plan and claim teachers union agreements are a root of the problem. In court documents, the union and district have defended their actions.

The court documents — connected to a September lawsuit over distance-learning — offer insights on how union negotiators, through an August agreement with the district, shaped instruction for the current school year. About 70% of students are likely to remain online as their campuses reopen.

The documents show that district negotiators wanted a distance-learning program that more closely resembled a traditional school-day schedule. The union pushed back: Too much screen time would be detrimental to students. Student and teachers would benefit more from a flexible schedule, which, to the union, meant a shorter school day and less required live online instruction.

A group of parents is seeking a court order to pressure the L.A. school district to reopen full time, five days a week for all students.

The final pact resulted in L.A. Unified requiring the fewest live instructional minutes among the five largest school systems in California, according to research released last month from the advocacy group Great Public Schools Now — although there is little question that many district teachers have far exceeded the minimums set in the agreement.

Under the agreement, the minimum live online instructional time for L.A. Unified elementary students was set at 114 minutes. For neighboring Long Beach Unified, the state’s fourth-largest school system, the figure is 255. For middle and high schools, it’s 138 minutes in L.A. Unified and 300 in Long Beach.

The back and forth of the negotiations are laid out in meeting minutes, emails and proposals filed with the court.

High school students recall their year at home as they prepare to return to campus for the first time since the pandemic began.

Entering into the negotiations, L.A. Unified had come under criticism, in the spring of 2020, for not requiring teachers to provide live online instruction amid the emergency response to close down campuses.

“Don’t want to lose our parents,” said Chief Academic Officer Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, according to meeting minutes for July 16, 2020, which are not word-for-word transcriptions. “They want to know we are committing to a full day. That their $ are going to really support kids.”

“We got beat up pretty good by parents,” said district Director of Labor Relations Tony DiGrazia on July 23. “Biggest concern, teachers getting full pay and not putting in full day; I am tryin[g] to address; if it appears it is same way it is going to be a problem.”

“We got so much heat in the spring, and continue to get heat now about 4 hours,” added Yoshimoto-Towery, referring to the required length of the teacher work day in the spring of 2020.

A traditional teacher workday would include six hours on campus with students plus about two additional hours for supplementary work on or off campus.

Union negotiators countered that the district should not give in to misguided public pressure — either from the media or from more privileged parents who, they said, did not represent the views of most families, court documents showed.

Los Angeles parents filed a class action lawsuit against Los Angeles Unified, saying the district is failing to provide students with their constitutional right to an education during distance learning.

The union team emphasized that their members had been talking to Spanish-speaking parents — who don’t “make over 100K,” said Grace Regullano, the union’s strategic research and analytics director in the minutes. “That needs to be taken into consideration; when talking about equity, who is being heard; we are hearing guardians in Spanish, [who] are in lower income said they are satisfied” with what teachers had been providing.

District officials asserted the importance of maintaining familiar schedules and providing adequate instructional time.

“We see a need for live video, need a defined school day, and would like to see the work day mirror or parallel a regular work day,” DiGrazia said on July 16. “Can’t shortchange the students.”

The union team countered that the district was taking too narrow a view of instruction, asserting that excessive screen time would be detrimental. “It’s hard for adults to be on Zoom for 3 hours a day,” said Julie Van Winkle, the union’s vice president for secondary schools. The union team also objected to any insinuation that teachers would not work beyond the required minimum.

“Our teachers have been making themselves available 18-20 hours a day” Gloria Martinez, the union’s elementary vice president said on July 31. “It’s a little bit insulting to assume we will not do what is best.”

The union gave some ground, but well short of what the district team said it wanted. The union also prevailed on reducing the school day: The revised schedule ran from 9 a.m. to 2:15 p.m. rather than from about 8 a.m. to about 3 p.m. Union negotiators insisted that students and families needed the flexibility as well as teachers.

“Some high school students are working to support their families, and won’t be able to make (class time),” said Van Winkle.

‘My parents’ worries became my own.’ L.A. students have taken on grueling work to support their families during the pandemic.

In a statement last week, the union said that the parent plaintiffs in the distance-learning suit have failed to acknowledge that an online day should not be compared directly to a traditional school day.

“The virtual day is necessarily different from one spent on campus, where there are longer breaks for lunch, recess, class changes, and time to answer individual questions while students complete assignments in the classroom,” the statement said. “The in-person school day has never been eight or even six hours of nonstop lecturing (and students generally do not spend eight hours a day on campus), but includes various modes of learning and that variety has been adapted into the remote models.”

When it comes to safety issues — such as distancing, improved air filtration and coronavirus testing — the court records show substantial agreement from the outset even though there were important details to work out, including how school safety committees would operate.

As the distance learning agreement took hold, negotiations continued — although details of those talks have not been made public. However, the terms of various union side agreements that gradually emerged played a role in L.A. Unified lagging behind many other school systems in providing in-person services to students with special needs, such as those with disabilities and students learning English. Tutoring and other help for students reached fewer than 1% of district enrollment before officials shut down all in-person contact during the deadly fall and winter coronavirus surge.

The district declined to respond for this article. In a public letter to the editor of The Times, responding to the latest lawsuit, a district official noted that elementary students will have five days on campus with the addition of child care to cover the span of 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. — more than some other districts are offering.

The union, in its statement, asserted that the labor pacts comply with state law and there is support for this.

The county education office confirmed that the state did not require any particular amount of live online instruction for this school year. The only “live” requirement is for a daily check-in.

“UTLA educators have unapologetically prioritized community, student, and staff safety during the uncertainty and dynamic environment of the worst pandemic of our lifetimes,” union President Cecily Myart-Cruz said in the statement. “Educators in L.A. have worked harder and longer hours than any other time in our careers.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.