In the midst of their battle against COVID-19, a medical team celebrates life

On a cold Tuesday evening in January, Blanca Lopez and her son Criztiaan Juarez drove from their home in Glendale to the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Traffic was light through the valley and over the Sepulveda Pass.

Lopez had been busy that day, going to a hair salon, getting her lashes done, preparing dinner for her family in her absence: chili colorado with nopales and Peruvian beans for her parents, spaghetti with smoked sausage for her children.

Five months earlier, she had nearly died of COVID-19, and an ambulance, following the same route she drove today, took her to UCLA.

As she pulled into a small parking lot outside the emergency room, she saw two tan, squat tents set up on either side of the entrance. She felt herself tense with the memory of having waited in one.

For the sickest of the COVID-19 sick, ECMO has become a final option.

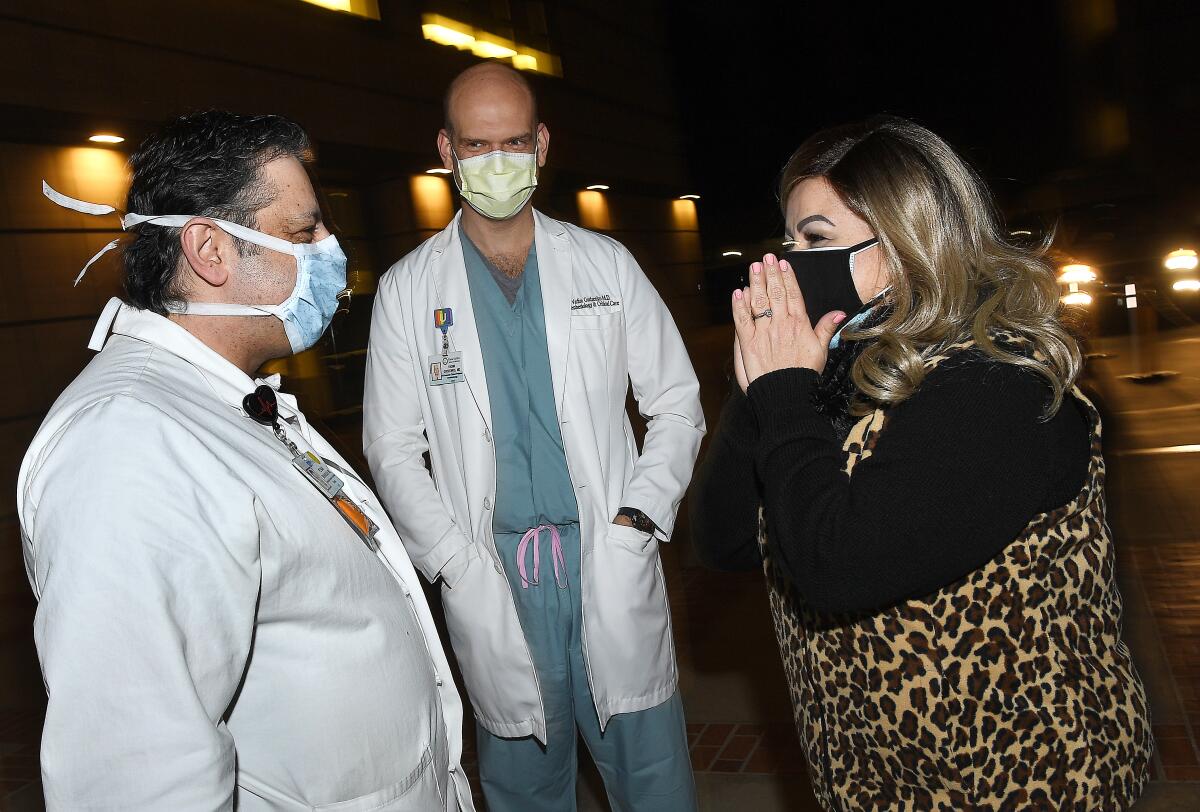

But that was long ago. Today a representative from UCLA escorted her through the hospital’s gleaming lobby of marble and glass. At the main entrance, in a courtyard by a fountain, stood a group of physicians, nurses, emergency medical technicians and other specialists. Some had driven in on their day off. Others were ending or beginning their shift.

They wanted to see their patient again, this woman who had spent 51 days in the intensive care unit on a medical device that offered no guarantee for a reunion like this. Lopez had almost died and yet, somehow, survived.

She didn’t quite know what to say, and they helped with applause and arms outreached in socially distanced air-hugs. Rarely do medical teams, especially in the intensive care unit, have an opportunity to meet patients once they leave the unit.

“It is so good to see you,” said Susan Valentine, a nurse practitioner.

A nurse, Lindsay Brant, stepped up and — impulse overcoming restraint — hugged her.

“Thank you,” Lopez said. “Thank you.”

Her recovery had depended on a machine known as ECMO that circulated and oxygenated her blood outside her body. It is reserved for the sickest of those infected with COVID-19, those who show no signs of improvement after being put on a ventilator.

“It is so nice to see the people who took care of me,” Lopez said, “to know there are people with such kind hearts. You do your job not just for the money like other people do. You do the stuff you do because you love to help people.”

The path to developing ECMO included stops at a Boston animal shelter and a Santa Barbara hospital.

She tried not to cry and spoil her eyeliner and cat-eye lashes as they all stood for photographs.

Dressed in blue scrubs and a white surgical coat, Dr. Peymon Benharash, a heart surgeon, stepped up. He wanted to make sure Lopez wasn’t chilled. Her immune system was still weak.

“Is there any way we could move inside?” he asked.

Since Lopez had left UCLA in late October for a rehabilitation closer to home, Benharash has fielded inquiries from doctors as far away as Fresno and Arizona, trying to get their most critical patients on ECMO.

“Last December,” he said, “I took 20 calls in one day.”

Dr. Vadim Gudenzko, an intensivist, listened as Lopez pieced together her memories: the terrible thirst, the first steps she took still hooked up to the machine. He was impressed that her mind was so clear.

Her recovery was rare validation that he and the medical team are making the right decisions for their patients. Lopez’s course of treatment wasn’t easy. Caring for anyone on life support for 51 days is harrowing, and even if they make it, Gudzenko worries about their quality of life. Will it be the same as before?

“It is hard on patient and staff to care for someone who is so ill,” he said. “It is emotionally draining, but if you can get someone like Blanca back to her family — and then have a photo session three months later — then it is worth it.”

Brant was especially thrilled to see Lopez. She re-created the shoulder-shimmy dance that she and Lopez had perfected during their time together.

“I want you to know how courageous you are,” she said. “This is something you need to carry for the rest of your life. People just don’t get better from COVID. It takes heart.”

In recent months, Lopez has lost three family members to COVID-19, and she wrestles with her fortune, wondering why her doctors decided to do whatever they could to save her life.

“I don’t know how to explain it,” she said. “I don’t know how or why God gave me so much.”

In this strange lottery, she won the prize, mindful that thousands of others — even those more financially secure than she is — haven’t. But as her mother reminds her, “money can’t buy life.”

As photographs were taken, Criztiaan, 18, stood apart. He stared up at the hospital’s lit windows, where so many sick patients were now fighting for their lives, just like she had.

He remembered the times he visited last summer.

“I felt hopeless,” he said, afraid that one day he would no longer have a reason to come back.

As the reunion ended, goodbyes were said, and everyone promised to meet once again as soon as all of this — the pandemic — was over.

Walking through the lobby to the car, Criztiaan had passed the yellow cushioned benches where he had waited along with all the other families. He sat down on one and prayed.

“For anyone who goes into the hospital, that they will make it out alive,” he recounted later, “and if they don’t, then for the people who are close to them, so that they won’t feel too much pain.”

Driving home that night, Lopez and her son talked, and she finally allowed herself to cry.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.