Beds filling halls. Agonizing ER waits. Burned-out staff. Inside overloaded California hospitals

When Erick Fernandez’s alarm goes off at 4:30 a.m., the stress begins.

As an emergency room nurse at Antelope Valley Hospital in Lancaster, Fernandez said his 6 a.m. shift marks the start of a long day. The hospital is home to one of the busiest ERs in the state, and like many, it has been overrun by COVID-19.

“The surge is definitely in full force,” Fernandez said. “Sometimes we come in in the morning, and a lot of the areas are just full of COVID patients already.”

In the last week, California has averaged more than 32,000 coronavirus cases each day, according to The Times tracker. That’s a 129% increase from two weeks ago. What’s more, those figures are also contributing to higher hospitalization rates than at any other point during the pandemic.

To the outside world, the numbers may be little more than statistics, but inside Southern California’s hospitals, conditions are rapidly deteriorating as beds fill up and workers burn out.

Annel Meza, an emergency room nurse at Riverside University Health Systems, said hospitalizations are increasing so quickly that staff has resorted to putting patients’ beds in the hallway.

“Sometimes there’s no beds at all,” she said.

One patient, who was admitted Dec. 1, was in the hall for four days. Wait times in the emergency room have grown so long that some have given up and left, thinking if they had to wait that long, they must not be that sick, Meza said.

At least three counties in the San Joaquin Valley were among the first in the state to run out of ICU beds.

The number of patients has increased so steadily that the Riverside hospital has had to apply for a waiver to bypass state-mandated staff-patient ratios, spokeswoman Heather Jackson said.

More than 180 hospitals across the state have applied for staffing waivers, according to the California Department of Public Health — a testament to how radically the latest COVID-19 surge has upended operations.

Adding even one extra patient not only contributes to staff burnout, it also sets a dangerous precedent: The more patients a doctor or nurse has, the less care each gets. One widely cited study found that each additional patient a nurse has is associated with a 7% increase in mortality.

“It’s definitely moving into that all-hands-on-deck period,” said Dr. Joanne Spetz, director of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at UC San Francisco, who studies nurse staffing. “Especially because, looking at these hospitalization numbers, the burnout and the stress for the workforce is probably not going to get better that rapidly.”

The COVID-19 vaccine continues to roll out throughout Southern California.

Staffing shortages are exacerbated by workforce dropout, Spetz said. After gruelingly long shifts, healthcare workers’ daily rituals include showers, laundry and disinfectant at home in an attempt to protect their loved ones. Spetz said many have left their jobs because they or family members have contracted COVID-19 or because they’re worried about the ongoing health risk.

Meza, who is 6 months pregnant, said she has had to weigh the need for work with concerns about her safety, as well as the safety of her husband and 11-year-old daughter.

“Every day I see at least 10 people that have COVID, so I get a little bit more scared,” she said.

But while the vaccine offers promise, it comes as the U.S. is facing the darkest moment of the coronavirus crisis. On Monday, the U.S. death toll topped 300,000, and California, like much of the nation, is in the throes of the worst wave of the disease.

Similar scenes are playing out in hospitals across the state, where climbing caseloads have become such a cause for concern that all but two regions of California are under stay-at-home orders triggered by ICU capacity.

The Southern California region, which includes Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, has just 0.5% of its ICU beds available, according to state data, down from 7% just days ago. As of Tuesday, Los Angeles County had fewer than 100 ICU beds, while Riverside County was at 0% capacity.

At Dignity Health California Hospital Medical Center in downtown Los Angeles, so many patients have arrived in the last two weeks that doctors’ mid-morning rounds have been substantially shortened, said Dr. Simon Mates, the ICU’s co-director. Instead of the usual five or 10 minutes spent with each patient, they’re down to two or three minutes apiece, he said.

In San Bernardino, the surge came so rapidly that county officials have limited ambulance calls, a decision prompted by skyrocketing ICU and hospital numbers.

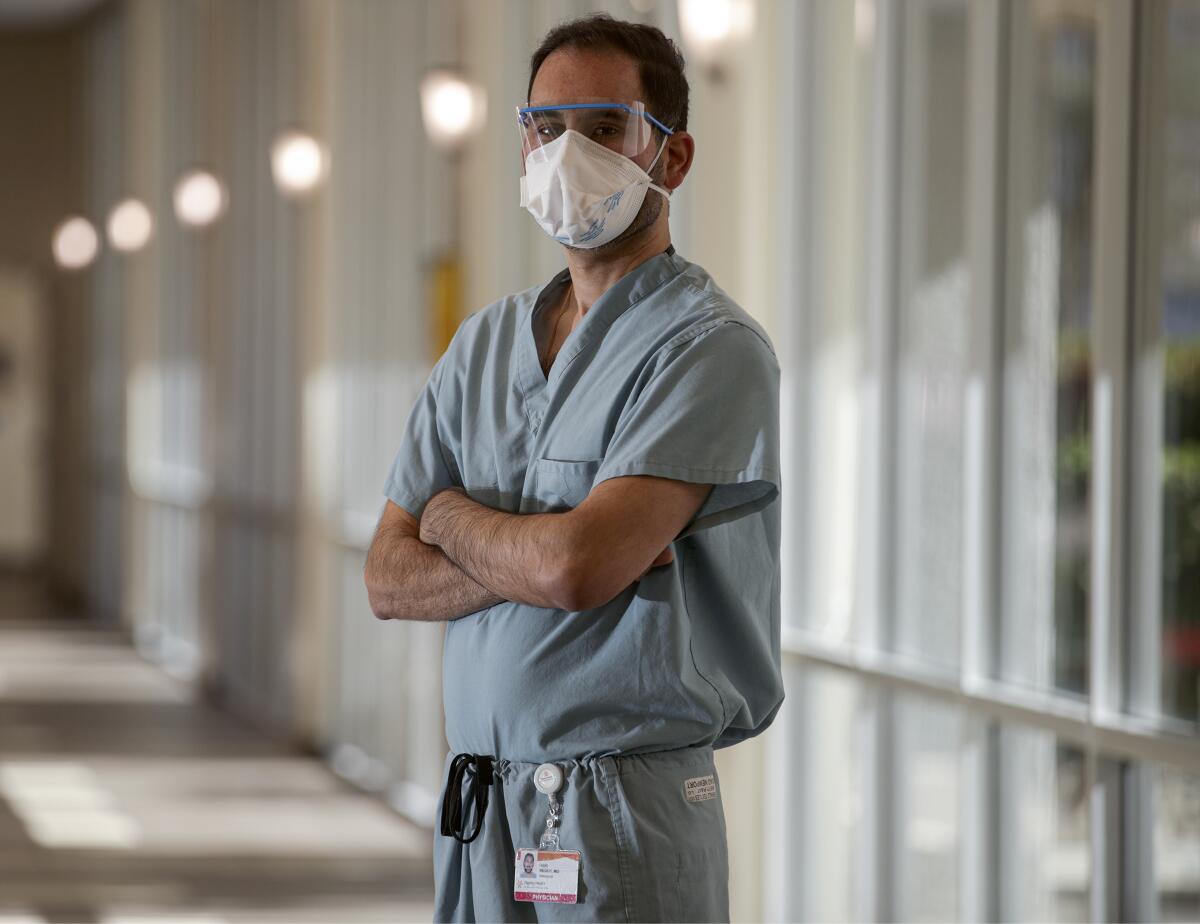

At least one hospital in the county is already feeling the strain: Dr. Hari Reddy said that St. Bernardine Medical Center’s 47-bed ICU has been steadily filling in recent weeks and that the flood of COVID-19 patients is forcing some doctors to make difficult decisions.

“There’s been times when we’ve had multiple patients having cardiac arrest at the same time, and we’ve had to really triage to figure out which patient to resuscitate first,” said Reddy, the hospital’s intensivist medical director. “If there’s multiple emergencies, I try to gauge which patient I can make the most difference in.”

As medical providers plead with their communities to help them control the coronavirus, some workers and business owners say they can’t afford to listen.

What’s happening now — the so-called third wave of the pandemic — is far worse than what most hospitals experienced earlier this year, Reddy said. COVID-19 patient volume is nearly double what St. Bernardine saw earlier this year.

And while most doctors and nurses say their understanding of the illness has improved and treatments are more effective, the virus still finds ways to shock and surprise. The first wave was characterized by clusters, such as nursing home patients who became sick during outbreaks, Reddy said. Now he’s seeing the virus in young people in their 20s and 30s, and quite often infecting entire families.

“A universal factor in a lot of these patients is they typically had somebody in their family that had the disease as well,” he said. “It’s spreading through the households.”

The family factor has been increasingly documented, with many experts pointing to Thanksgiving gatherings as a flashpoint for the most recent surge.

Reddy is now hoping that people will heed health warnings come Christmas.

“Everybody has their own beliefs, but I would love for any one of them to come live life in the day of a nurse or a respiratory therapist who has to go into a COVID room multiple times every hour, or just walk through the ICU to see how sick patients are,” he said. “I think it would really change people’s opinions.”

Health experts also emphasize how the virus’ spread can be prevented by social distancing and wearing masks.

Public resistance to such practices, said Cedars-Sinai Medical Center ICU director Dr. Isabel Pedraza, can be disheartening.

“You can spend the majority of your day really fighting to keep some of these patients alive,” Pedraza said. “Seeing their suffering and their family’s suffering, and then walking out the door and listening to news about how this isn’t a big deal, and how wearing a mask is infringing on constitutional rights, and how this is a hoax … it takes its toll.”

Patient numbers in her unit have increased steadily. A month ago, the Cedars-Sinai ICU was at half-capacity, Pedraza said. Now it’s closer to two-thirds.

Lately, much of her afternoons have been spent calling families to update them on the condition of their loved ones, whom they cannot visit in person. It’s a process that drives home how cruel the virus can be.

“To see the fear in their faces, the isolation — I don’t think people understand what they’re in for if they develop severe COVID,” she said.

Like many Americans, hospital workers are looking forward to the widespread distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine and see it as a potential sea change. Mates, the ICU co-director at Dignity Health California Hospital Medical Center, even participated in the Pfizer trial, noting that he is eager to see the vaccine take some of the pressure off frontline workers.

But vaccinating all Californians will take time — the state’s initial allocation is only about 327,000 doses — and experts say the general public likely won’t receive their shots until the spring or summer.

It feels like a distant finish line for a hospital system hanging by a thread and healthcare workers struggling to adapt to a rapidly worsening situation.

“We saw what happened in New York when hospitals were overwhelmed because they didn’t have enough people or equipment,” Pedraza said. “The limiting factor is really, are you reaching the maximum of your resources that are available?”

With daily death tolls repeatedly breaking records, many are bracing for the uncertainty of what comes next.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.