FRESNO — The last time Dr. Eyad Almasri had a day off was in November, when he was infected with the novel coronavirus. His symptoms were not life-threatening, but it crushed him, he said, that he couldn’t be with his patients for 10 days.

A pulmonologist with the Fresno campus of UC San Francisco, Almasri works in the intensive care unit at Community Regional Medical Center in downtown Fresno — so packed with COVID-19 patients that the hospital has had to create makeshift isolation wards, including one in a hallway. Exhausted staff, working long hours seven days a week, rarely take off their protective gear because the entire area is the “dirty zone” — a phrase Almasri detests. With so many patients, there is no time for breaks anyway.

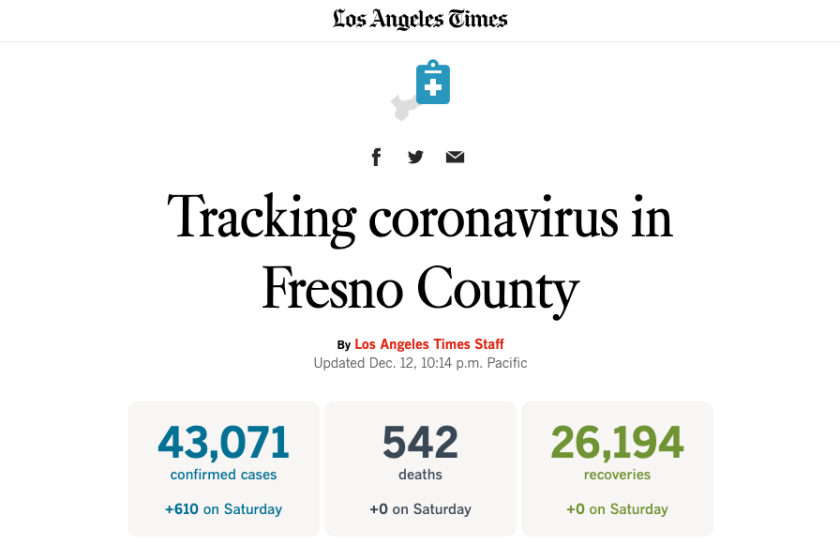

The story was similar this week in much of the San Joaquin Valley, where hospitals were crowded with COVID-19 patients. As of noon Saturday, availability of ICU beds in the region was zero. Fresno, a metro area with more than 1 million people, hit that dubious marker two days earlier.

“There is no help on the way,” Almasri said Thursday. “I can’t tell you how scared people are, and I can’t even sit there and hold their hands. There are so many others waiting.”

Across California, medical professionals such as Almasri live a world apart from average citizens, who have no clear window into the conditions of hospital wards. But the San Joaquin Valley is different. Nowhere else in California do intensive care doctors and nurses work in such a fragile system.

It’s an agricultural valley with high rates of poverty and a staggering shortage of doctors. Yet during the pandemic, many local leaders have been openly defiant of public health directives.

The Fresno City Council on Thursday approved an order intended to clamp down on backyard parties, for what it was worth. But the city police chief quickly issued a statement saying his officers would not enforce it. Meanwhile, coronavirus cases continue to soar in the county, in part because of outbreaks at a Foster Farms poultry plant and a state prison.

In Stockton, in the northern part of the San Joaquin Valley, some small-business owners are demanding a reprieve from closures, arguing that this third round is arbitrary and unfair. They say there is little sense in having large chains such as Target and Walmart, where workers come into contact with hundreds of customers a day, remain open while shutting down outdoor dining for neighborhood eateries and services such as salons. Closing again, they contend, may mean that they go under permanently — a financial catastrophe for them and their employees.

Photos look back at 2020’s wild ride in the Golden State.

“The hospitals are not overflowing because of restaurants,” said Johnny Hernandez, co-owner of the Black Rabbit gastropub in Stockton, who joined a protest with other small-business owners Thursday on the steps of Stockton City Hall. Hernandez said he has let go seven of his 10 employees and doesn’t have the funds to make it past this month. For him, the threat of financial ruin is more real than the specter of illness.

“I don’t see Republican; I don’t see Democrat,” said the former union organizer. “I see people hurting.”

The valley is a diverse place, with complex opinions on the pandemic. Farmworkers and other essential Latino workers have been hit hard and are scared that the coming months will be even tougher. But with many lacking legal immigration status and unable to receive state aid, they must work to put food on the table. Many business owners also recognize the seriousness of the pandemic and are taking precautions to protect themselves, their families and employees.

But as elsewhere, conspiracy theories are rife — in particular the belief that public health orders are the first step to full government tyranny.

Some resisters — aided by the same groups that have staged anti-vaccine rallies and protested coronavirus restrictions, including religious leaders opposed to curtailing church services and the far-right Proud Boys — have banded together to demand the declaration of “sanctuary cities” for businesses, where they would be exempt from state lockdowns.

Almasri, the doctor in Fresno, is well aware of the misinformation campaigns and politicization around the pandemic. He sees it when he returns to his neighborhood.

“My own neighbor told me they thought COVID wasn’t real — a scam for hospitals to get money from the government,” he said. “I said, ‘What are you talking about? I’m there every day. I’ve seen people die.’”

In Fresno County, more than half of coronavirus cases have been in the Latino community, and more people younger than 75 have died than those older, according to data from the county. Cases in San Joaquin County have also skewed young, with most of those who have contracted the virus between the ages of 20 and 60, the county says.

But now the wards are filled with people of every description.

Because of the crowding, Almasri said, doctors and nurses are getting ill, when resources are already stretched.

“I don’t think it’s from patients. It’s because there is no room for social distancing. We don’t have time to leave the hospital, so we crowd into a break room to grab a quick bite to eat,” he said.

To protect himself, Almasri has six N95 masks that he keeps in rotation. They have to be worn very tightly, with a plastic shield over them.

“It changes the sound of my voice. I look like an alien, and I’m having life-and-death conversations with people: ‘Do you want to be put on life support if you get worse?’”

When he goes home, he sleeps in the mother-in-law house in his backyard to protect his wife, who is also a physician, and their three children.

In the field for 25 years, he has never been more proud to be a doctor, he said. Despite the odds, Almasri and his team have been able to help the same percentage of patients overcome COVID-19 as those in better-served areas.

“We’re saving lives,” he said. “We just can’t save everyone at once.”

He said if he could tell people anything about what is happening at the hospital, it would be, “Help us. Wear a mask.”

One hundred miles north of Almasri’s hospital, the parking lot at the upscale Lincoln Center shopping center in Stockton was packed Thursday. Shoe stores, jewelers, juice bars and bakeries were legally serving patrons — some masked, some not.

In defiance of the shutdown orders, servers at Midgley’s Public House delivered burgers and beers to tables indoors while the owner and a handful of regulars drank at the bar. Nearby, stylists at Pomp Salon were busy folding highlighting foils and brushing hair dye onto the heads of about a dozen clients, all distanced and wearing masks.

Pomp stylist Paula Turner said she needs to be working and was grateful that the salon’s owner said he would stay open no matter what the state ordered. When the salon closed in March during the first shutdown, she fought for months for unemployment payments, eventually receiving them. But recently, the troubled Employment Development Department demanded the entire amount back, she said, claiming she does not qualify. She believes the virus is real and deadly, but she also believes she can see her clients safely.

“I’ve got to work. I’ve got to eat,” she said. “If you could tell me one single person who got it at a hair salon, I would be nervous.”

Her client Marsha Mahnke said she is a widower whose children are grown and gone. The pandemic has been isolating.

“I don’t want to be home alone and looking at my gray hair,” she said.

State Sen. Andreas Borgeas (R-Modesto) called the blanket restrictions an “unsustainable path” with immediate consequences. He said the state needs to find a way to handle its economic and health crises at once.

The coronavirus is “absolutely devastating our ICU bed availability, and we also know the valley’s economy is in tatters,” he said.

Friday, he introduced a bill with state Sen. Anna Caballero (D-Salinas) that would invest $2.6 billion in grants to help struggling businesses and their employees.

Borgeas’ assertion of immediate need can be seen at Stockton’s Emergency Food Bank, where California National Guard troops on Thursday helped load apples, chocolate milk and other groceries into the trunks of a long line of cars. The food bank has seen a 15% increase in customers since the latest lockdown, on top of a 50% increase already this year, said its chief executive, Leonard Hansen.

But the need goes beyond food.

Elvira Ramirez, executive director of Catholic Charities in Stockton, has been helping to distribute cash aid to migrant workers and others. Though the organization is down to the last of its funds, the requests have not stopped, she said. Every day, her desk is filled with pleas, often written in Spanish, for help to pay rent and utility bills that have stacked up as agricultural work declined this year and the virus closed or curtailed operations at meatpacking plants and other processing facilities.

“It’s about work and how are they going to make ends meet,” she said of the requests.

At the same time, Ramirez said, many of these Latino workers have experienced the virus in their families, with loved ones who have died.

“The way they frame it is very different,” she said. “Not a single one of the 500-plus families we’ve helped in recent times is going to say we shouldn’t shut it down because of their personal rights.”

But some witnessing the pandemic’s toll on the lowest economic rungs share the concerns of the business owners.

Around the corner from the food bank, at Stockton’s Gospel Center Rescue Mission, which runs the county’s only shelter for homeless COVID-19 patients, the Rev. Wayne Richardson, who serves as CEO, said he expected the facility’s 36 beds to be filled in coming days, based on county information. Eleven were already filled with people recovering from the virus, and 17 of his staff members were in quarantine, he said, after a recent outbreak.

The facility’s chief operations officer, Britton Kimball, was one of those who caught the virus from community exposure; his wife and daughter also had mild cases. Like many here, he believes Thanksgiving gatherings and other family events are to blame for the spread. But he thinks shutdowns are not the answer.

“It’s like stopping a tidal wave with a toothpick,” said Kimball. “All we are doing is putting people in poverty.”

Though conditions in the San Joaquin region are dire, other counties are experiencing similar surges — and concerns over closures.

San Benito County Supervisor Mark Medina said he is wrestling with how to keep businesses afloat while protecting people’s health.

“We have to find a happy medium and look at the businesses that are currently being asked to shut down,” he said. “Is it really coming from hairdressers? Gyms? Restaurants?”

He said he is constantly gathering new information, hoping to provide the best guidance he can.

“You don’t know,” he said. “You’re making decisions based on info that is in front of you, and you are praying to god that the info you receive is vetted. The good and bad and everything in between. And you have to ask, is this truly right? Or is it one-sided?”

State Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), the only medical doctor in the legislative body, said he understands the rising anger among business owners but believes their position is flawed and ultimately will lead to worse economic devastation. He points out that unless the virus is contained, more people will become seriously ill, leaving fewer willing to go to those businesses that remain open.

“It’s not the government that is shutting down the businesses in the end. … What’s really shutting down the businesses is the virus,” Pan said. “Unfortunately, painfully, people will realize that they were wrong, and the ones who don’t, some of them will die. We can’t save people from themselves after a certain point.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.