Column: With the COVID-19 pandemic and a battered economy, California voters said no to more taxes

SACRAMENTO — California voters rejected an ambitious state ballot initiative to substantially raise business property taxes. But they approved many local tax and bond measures. Why the distinction?

One reason is that voters are suspicious of Sacramento politicians. The public may not especially trust local officials either, but they’re closer and can be better watched and held accountable.

Another reason is that voters this year are very anxious about the economy as the pandemic takes a toll on businesses, jobs and retirement savings. They didn’t want to unleash a major new property tax hike that might further cripple the California economy.

This is a deep-blue state with strong Democratic leanings. But on the landmark property tax proposal, Proposition 15, many Democrats voted like Republicans.

Democratic leaders and strategists apparently underestimated national surveys that showed there was one issue on which President Trump usually outpolled Joe Biden. It was on the question of which candidate would be best at handling the economy.

“People were incredibly nervous about their personal economic situations,” Democratic consultant Gale Kaufman says. “It’s really difficult to get people to spend money when they’re nervous about their own economic lot…. They didn’t want to screw up their 401(k)s.”

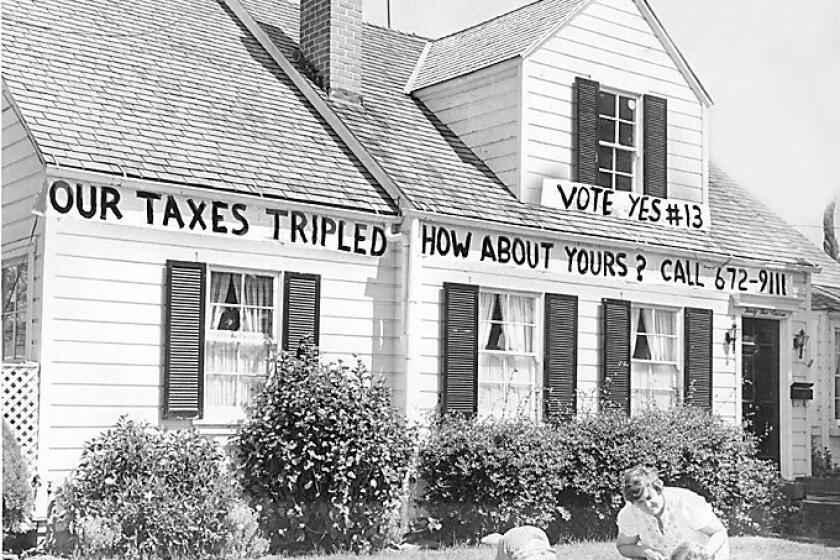

Another steep hurdle for Proposition 15 was that it asked voters to dramatically change Proposition 13, the historic 1978 property tax cut that’s viewed by many as sacrosanct.

Residential property would not have been affected, but many voters feared a camel’s nose under their tent. They suspected the tax-and-spenders would be coming after their homeowner tax breaks next.

Column: California’s tax system needs to be overhauled. Making changes to Proposition 13 won’t do it

With Proposition 15, voters are being asked on Nov. 3 to partially repeal a historic 1978 property tax cut that triggered a nationwide antitax revolt.

Under Proposition 15, commercial property would have been reassessed at market value every three years. Currently, that reassessment comes only when the property changes hands. And that’s almost never for big corporations using Proposition 13 loopholes.

Socking it to corporations is one thing. But a problem for 15 was that many small businesses lease their store sites and offices, and they would have been smacked. Under standard leases, the business owner is liable for the tax hikes.

“It’s time for the proponents [of 15] to accept the premise that Californians know the importance of Proposition 13,” says Robert Gutierrez, president and chief executive of the California Taxpayers Assn.

But consultant Larry Grisolano, the chief strategist for Proposition 15, says the measure’s close vote sends the opposite message.

“It’s indisputable that there’s an underlying demand in the California electorate for big corporations to pay their fair share,” he says.

OK, but the next time anti-13 forces launch an assault on the iconic law, they should focus narrowly on big corporations and be extra careful to exclude small businesses, even if the total tax take is smaller.

Proposition 15, sponsored by the California Teachers Assn. and the Service Employees International Union, would have raised up to $11.5 billion annually. The money would have been split 60% to local governments and 40% to K-12 schools and community colleges.

Business interests spent roughly $72 million to defeat the initiative. At this writing, voters had rejected it by roughly 52% to 48%.

But voters signed off on lots of local tax increases and bond issues. And under California’s stringent supermajority rules, most local tax increases require a two-thirds vote because of Proposition 13. School bonds need 55%.

Among proposed local sales tax increases, 53 were approved and 9 rejected, according to an early report by the California Taxpayers Assn. Several other measures were too close to call.

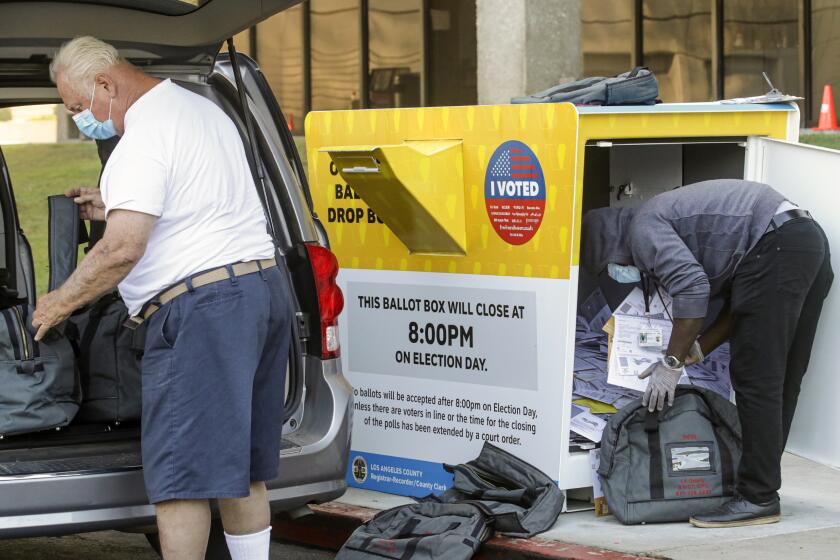

COVID-19 pandemic or not, California should continue to send every active registered voter a mail ballot in future elections. It makes voting much easier. And there are plenty of protections against fraud.

Of parcel tax proposals, 23 won and 13 lost. Forty school bond measures were approved, requiring property tax hikes. Only four were rejected, based on CalTax’s early look.

So why did these local measures pass — but Proposition 15 fail? There was an early warning sign.

In the March primary, a hefty $15-billion school construction bond measure proposed by Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature was rejected by voters. It was the first defeat of a state school bond measure since 1994, a very Republican year.

“In local school districts, voters know what’s going on,” Gutierrez says. “They understand what the money may or may not be used for. There’s a local connection to the community.”

That’s not the case with voters and Sacramento.

Proposition 15 was not placed on the ballot by the Legislature and governor. It was labor’s doing. And the billions raised would not have flowed into the state treasury. The money would have gone to local governments and schools. But it was strongly supported by Democratic leaders and the governor. The state’s brand was on the measure.

“People are not willing to give Sacramento a blank check,” says Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable, a leading opponent of Proposition 15. “They are willing to support taxes on the local level. We were glad to see some of these local things pass because the communities needed funds, whether they were from parcel taxes or bonds.”

“Local governments are more trusted,” says former Democratic consultant Darry Sragow, who publishes the California Target Book, which chronicles legislative and congressional races. “They feel that local officials are less likely to betray them.”

Grisolano says the pandemic both helped and hurt Proposition 15. Voters saw the need for raising more money to improve local public healthcare and education, he says.

“But it’s a hard time for people to contemplate major reforms when they’re right in the middle of something as profound as the pandemic,” he says. “The economic considerations that weighed on people’s minds certainly helped drive a ‘no’ vote.”

Yes. And voters also sent Sacramento Democrats a message: Forget huge tax increases.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.