NOAA’s La Niña watch could signal a dry winter for Los Angeles

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a La Niña watch earlier this month, meaning that conditions are favorable for development of a La Niña in the next six months.

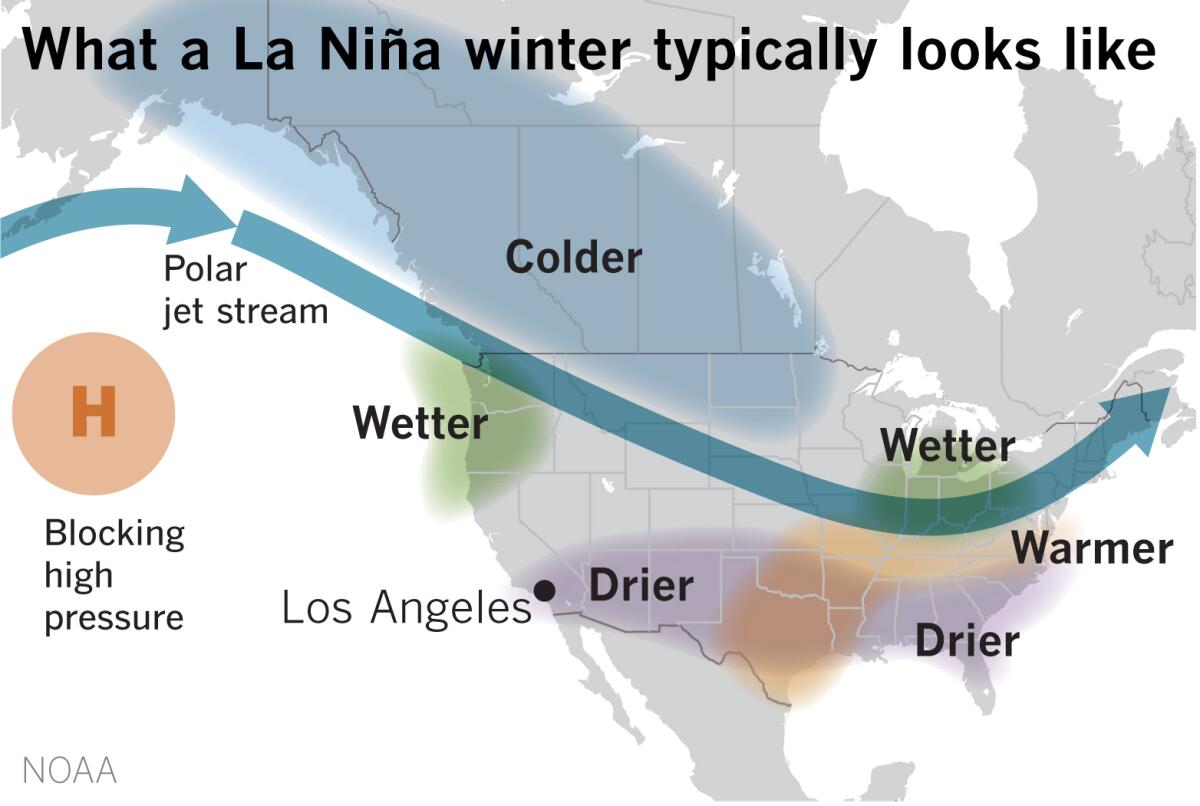

A La Niña typically means a dry winter across the southern United States, including Southern California.

La Niña is part of a climate phenomenon called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, often referred to as “ENSO.” It has nothing to do with the Ensos or their icy planet Ensolica in Star Wars, but La Niña is the cool phase of this climate phenomenon, and the opposite of its warm sibling, El Niño.

Between the two phases there is a neutral phase that’s neither El Niño nor La Niña — what climatologist Bill Patzert calls “La Nada.” That’s where we find ourselves at the moment — and where we expect to stay through the summer. But NOAA predicts that there’s a 50% to 55% chance of our current neutral phase shifting into a La Niña this fall and winter. Hence the watch. But there’s also a 40% to 45% chance, according to NOAA, that we will remain stuck in neutral for the fall and winter. In addition, there’s about a 5% to 10% chance of an El Niño developing.

While El Niño is usually associated with unrelentingly drenching winters in Southern California, La Niña is associated with drought. Patzert calls La Niña the “diva of drought,” and La Niña winters can be parched and fire-prone.

But California’s rainfall can be variable, as Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services points out. As an example, he cites the back-to-back winters of 2016-17 and 2017-18. “One was very wet, and one dry. Both weak La Niñas.”

The National Interagency Fire Center’s outlook for Southern California sees an expected transition to a La Niña episode adding drier-than-average conditions just as October arrives, bringing the start of the fall wind season.

The factors that favor the development of the warm, dry, down-sloping winds in the region — Santa Anas — may be more frequent, the NIFC outlook said, raising concern because of “the heavy loading of fine fuels” such as grasses and brush.

In California, rainfall can be enhanced by an El Niño and suppressed by a La Niña. While a wet El Niño season tends to reduce wildfires, it promotes the explosive growth of vegetation. Those weeds, grass and brush dry out in the summer, increasing fuel for wildfires. The potential for fire increases in subsequent dry or La Niña years. Some studies have suggested that this wet-dry cycle will be amplified in the future with climate change.

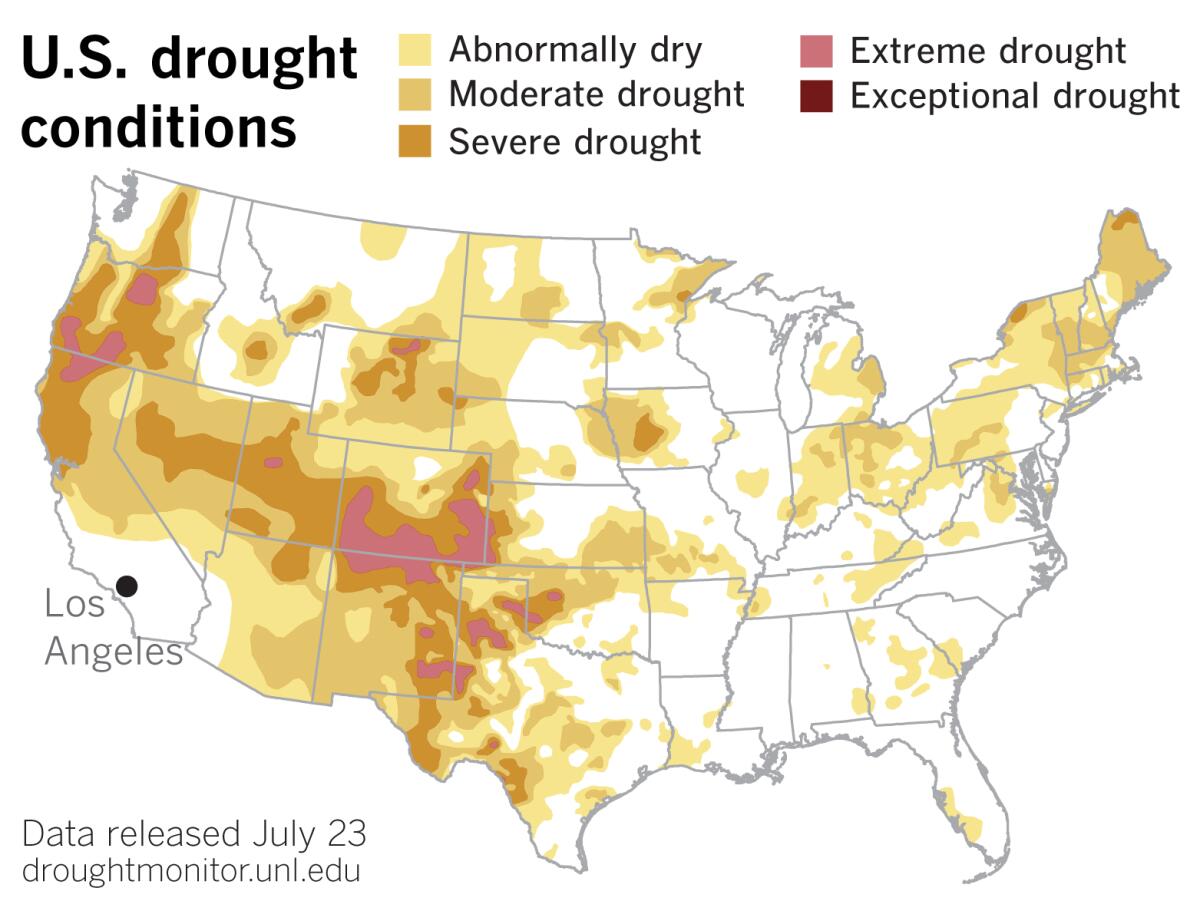

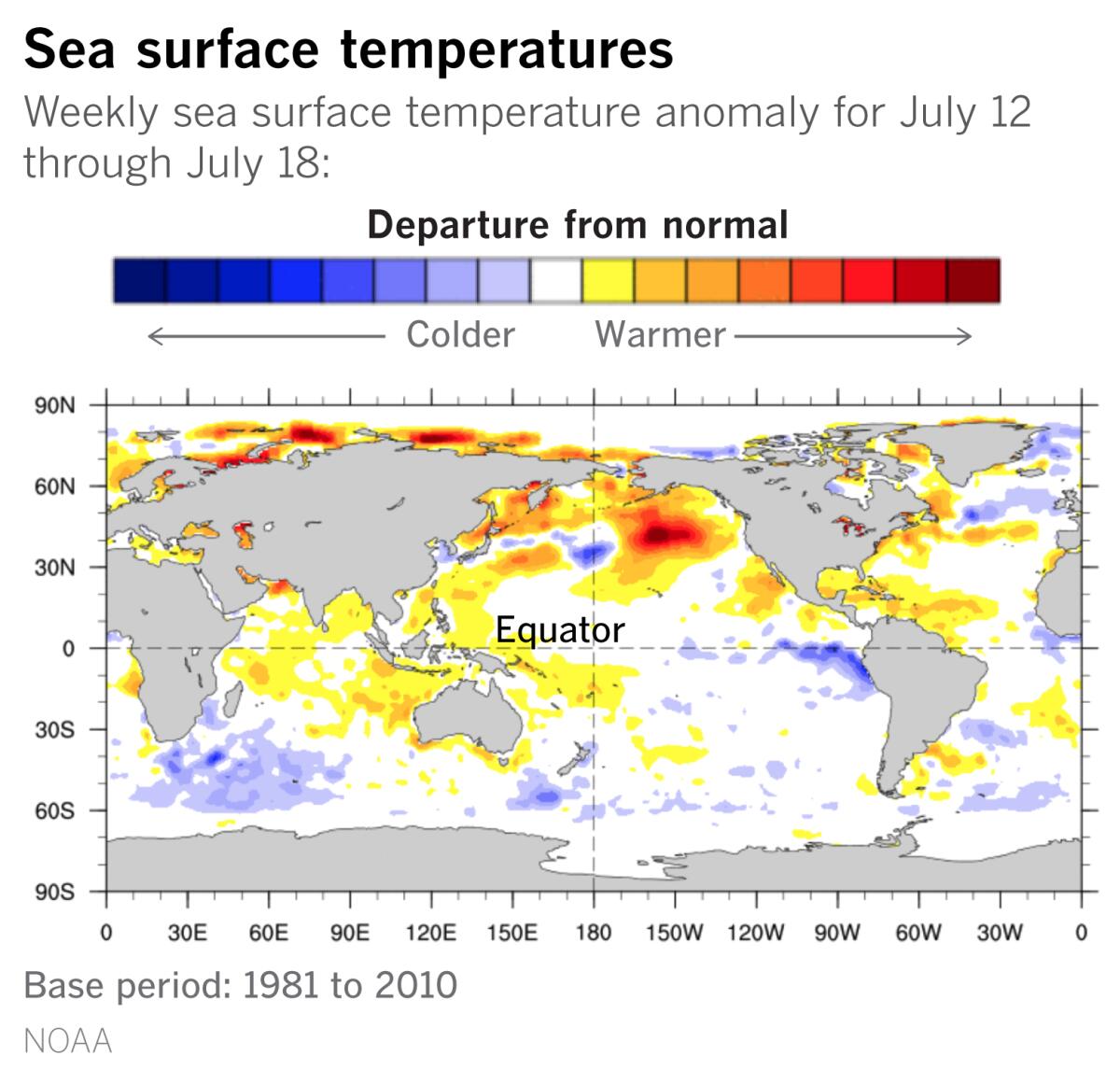

Even with ENSO neutral so far this summer, the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor data released Thursday show drought continuing to expand in the West. Most of California remained status quo, but the portion of the state considered to be in extreme drought expanded from about 2.5% to just over 3%.

In the Four Corners region, the Southwest Monsoon has been weak, so the region has remained dry. Drought conditions expanded in parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Oregon. Incipient La Niña conditions would suggest that hopes of relief may be evaporating.

Since the Pacific Ocean is the 800-pound gorilla of global climate, development of a La Niña can affect the weather for the whole world. “When the Pacific speaks, people all across the planet tune in,” says Patzert. “The impacts are felt globally: Drought in the American Southwest, deluges in Australia and Southeast Asia, and dramatic shifts in rainfall patterns over Africa.”

The pattern can cause the polar jet stream to shift to the north in the winter, not only causing the southern U.S. to be drier and warmer, but the Pacific Northwest, the Ohio Valley and southern Great Lakes regions can be wetter, and the northern Rockies and northern Plains can be stormier.

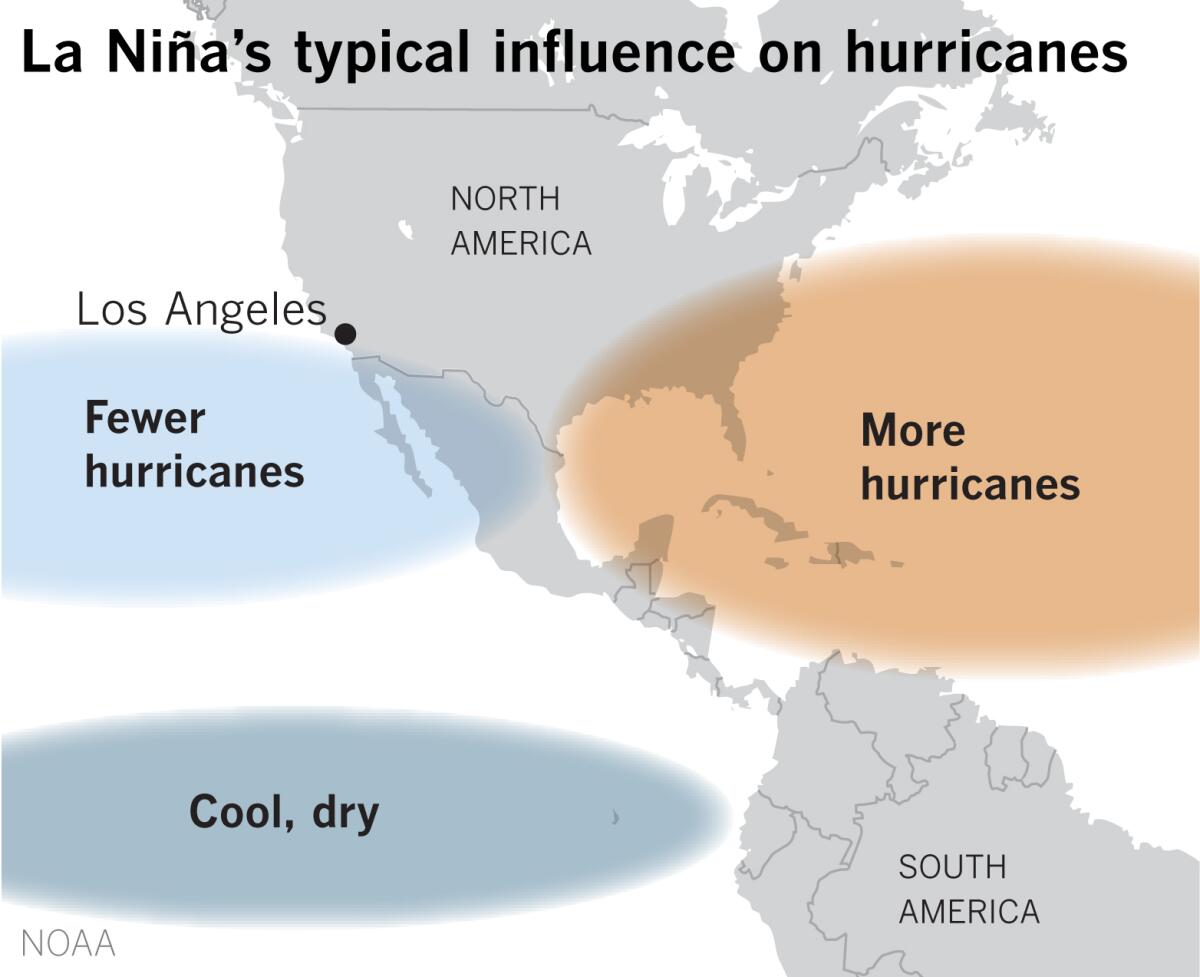

In the eastern Pacific, La Niña is associated with stronger vertical wind shear, which results in fewer hurricanes. But in the Caribbean, trade winds and vertical wind shear are weaker and there’s less atmospheric stability, leading to a more active hurricane season.

NOAA has predicted an active Atlantic hurricane season this year. The NOAA Climate Prediction Center in May predicted a 60% chance of an above-normal season, a 30% chance of a near-normal season and just a 10% chance of a below-normal season. The Atlantic hurricane season is from June 1 through Nov. 30, peaking in August and September.

The Atlantic has been in the warm or positive high-activity phase of the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO) since 1995. So continued ENSO-neutral conditions in the Pacific or a La Niña would mean either no suppression of, or reinforcement of, that high-activity inclination.

NOAA’s outlooks for the Central Pacific and Eastern Pacific call for near- or below-normal seasons for tropical cyclones and hurricanes.

Meanwhile, in the western Pacific, La Niña can cause heavy, flooding rains in places such as Indonesia and northern Australia.

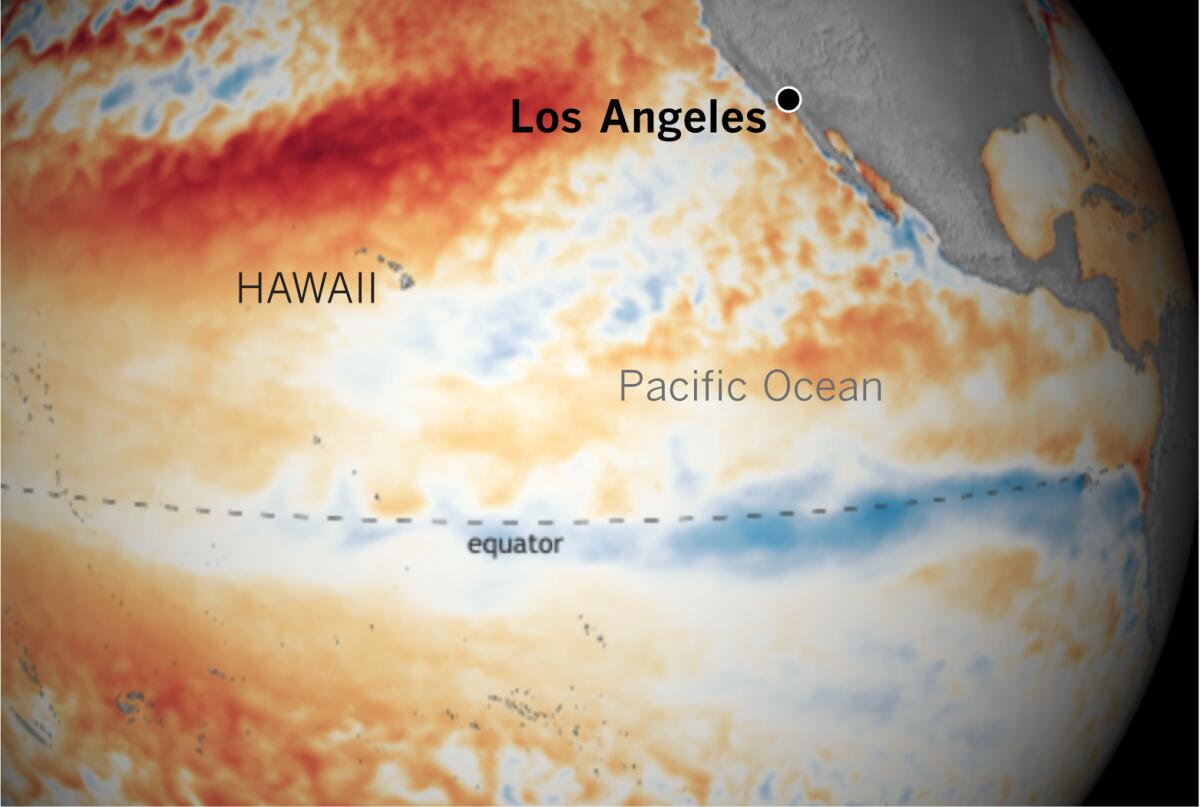

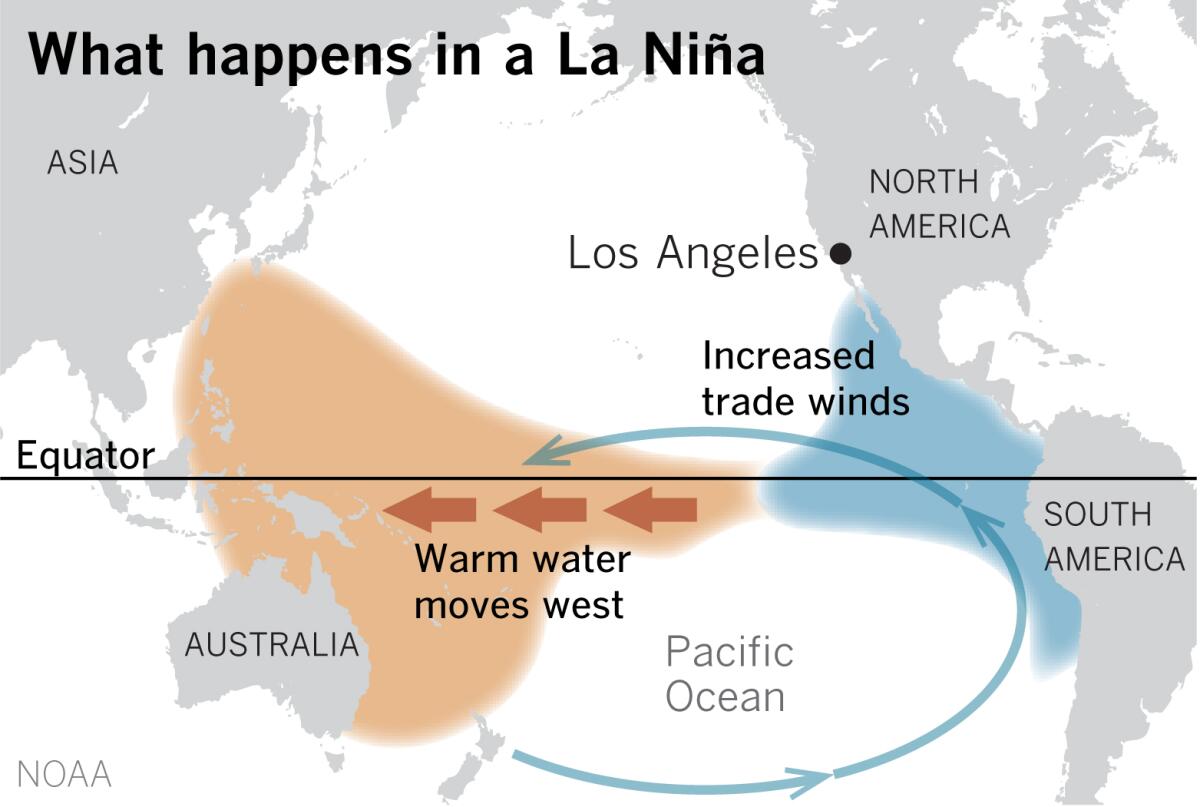

What causes La Niña? During a La Niña, the tropical trade winds are much stronger than under normal conditions, and they promote more upwelling of cold water from the deep off the west coast of South America and along the equator. The strong winds also push warm equatorial ocean surface water to the west. The warm ocean water causes more rain to fall in the western Pacific.

The ocean surface water in the eastern Pacific is only a few degrees colder than normal, but it can affect the weather around the planet. Because of this cooler water, less moisture evaporates and forms rain clouds, resulting in a much drier winter in places such as the U.S. Southwest. The changes in the atmosphere can lead to more lightning in the Gulf of Mexico and along the Gulf Coast.

Meanwhile, in Australia, the Bureau of Meteorology has also issued a La Niña watch, citing it as strengthening evidence that Australia may be headed out of drought. Australia’s last really wet winter was 2016, said Dr. Andrew King, a climatologist from the University of Melbourne. La Niña also increases the chances of flooding and cyclones in Australia.

“Even though NOAA hasn’t officially called this La Niña, climatologists around the world are anticipating its potential impacts,” Patzert notes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.