Among the ‘climate monsters’ that afflict California, Megadrought is the most reliable

As is appropriate for the state that is home to Hollywood, the “climate monsters” that bedevil California have names that sound like they came from B-movies — the Blob, Godzilla El Niño, Megadrought.

One monster in particular, Drought, has more than overstayed its welcome, according to a new study in the journal Science. So much so, according to the study, that a climate-driven megadrought that is as bad or worse than anything known in prehistory may be developing.

Southern Californians, emerging into the sunshine after an unusually wet stretch of spring, are likely to say, “What drought?”

Rainfall in downtown Los Angeles, for example, was more than twice what is considered normal in November and December. But then we got “bageled,” as climatologist Bill Patzert puts it. January and February, normally the wettest months, formed a dry hole in the middle of the rainy season. When Los Angeles should have been getting 3.12 and 3.80 inches in January and February, it got 0.32 and 0.04 of an inch, respectively.

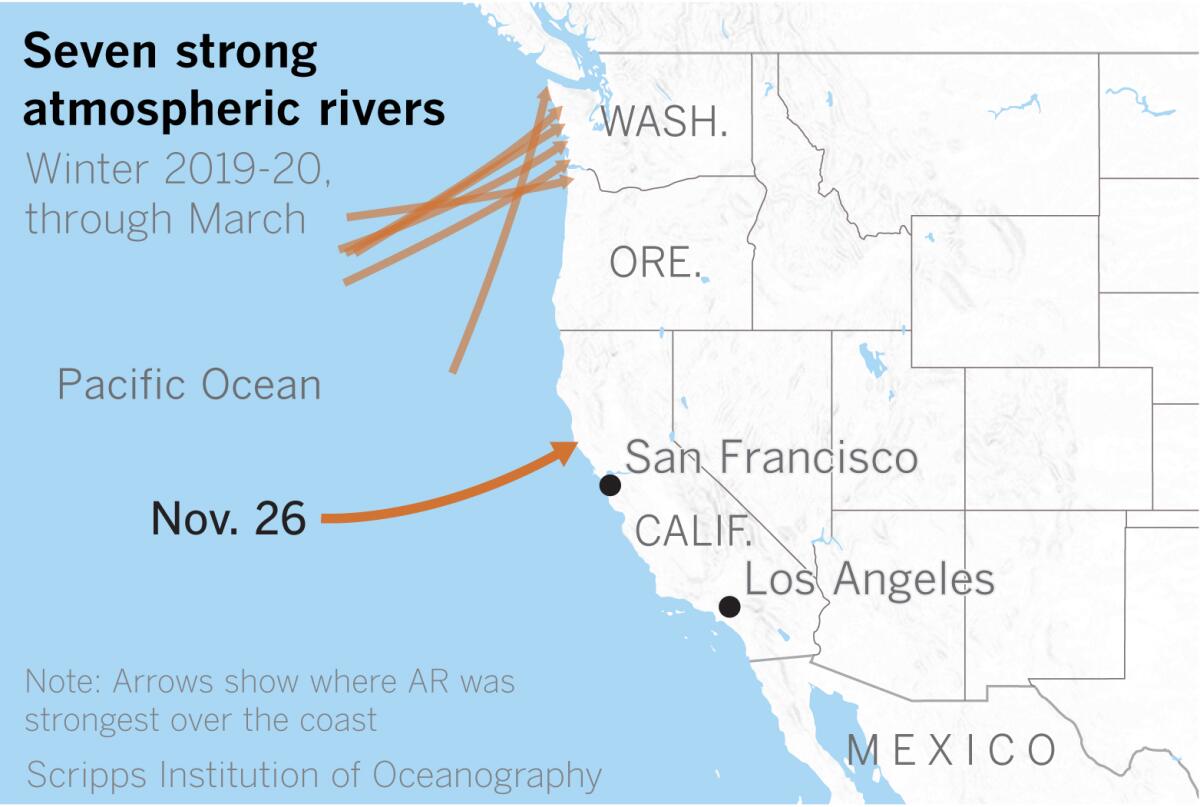

From October through March, 40 atmospheric rivers made landfall on the West Coast, according to the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Of those, seven were considered strong, and only one of those strong storms made landfall in Northern California — on Nov. 26. The rest hit Washington and Oregon, and no strong atmospheric rivers affected Central or Southern California.

During the previous year, 41 atmospheric rivers made landfall on the West Coast, but they were more spread out. More, stronger atmospheric rivers making landfall in California resulted in more precipitation in 2018-19.

“We are working on how best to count [atmospheric rivers], which is trickier than it might seem,” said Marty Ralph of Scripps. The period from October to March was especially low for atmospheric river counts in California and high in the Pacific Northwest, Ralph explained. The previous year was closer to normal overall but a bit above average for California.

Five moderate atmospheric rivers made landfall in California, all in December. Normally, four or five strong ARs can constitute a rain year, Patzert said.

In January and February, as a strong, stable polar vortex developed, high pressure in the eastern Pacific blocked storms aiming at California and sent them to the north, into the Pacific Northwest. The polar jet stream adjusted to the north, and the contiguous United States had its sixth-warmest winter on record.

Meanwhile, talk of “the Blob” returned as global ocean temperatures rose to the warmest on record, continuing a decadelong trend, and die-offs continued in marine ecosystems in the eastern Pacific.

After a record dry February, the blocking high shifted and hopes rose for a “March Miracle.” Some 4.35 inches of rain fell in downtown Los Angeles, nearly doubling the normal monthly rainfall. Then came April, a month when 0.91 of an inch would be expected in Los Angeles, but more than three times that much fell through April 10, as a cold low system more like a February storm meandered over Southern California.

This storm was a cutoff low that came down the coast and tapped into some subtropical moisture. When the polar jet steam adjusted to the north, the subtropical jet did as well. Although this wasn’t an El Niño year, the subtropical jet stream behaved more like an El Niño, feeding moisture into the U.S. Southeast, which experienced an unusually wet winter punctuated with severe weather and a caravan of tornadoes.

In the strong El Niño of 1997-98, the subtropical jet shifted north and downtown Los Angeles got slightly more than 31 inches of rain — more than twice normal. This would qualify as a “Godzilla El Niño,” to use a name coined by Patzert. The 2015-16 season also was setting up as a similarly strong El Niño, but the subtropical jet behaved more like the one during the El Niño-neutral 2019-20 season, keeping to the south and plowing rain into Texas. “It was the wettest winter and spring in Texas history,” Patzert said.

If you live in Southern California, where Los Angeles has received 14.69 inches of rain, or 106% of normal, you might indeed say, “What drought?” But as you move northward, it becomes clear that the bounteous moisture hasn’t been enjoyed by Northern California.

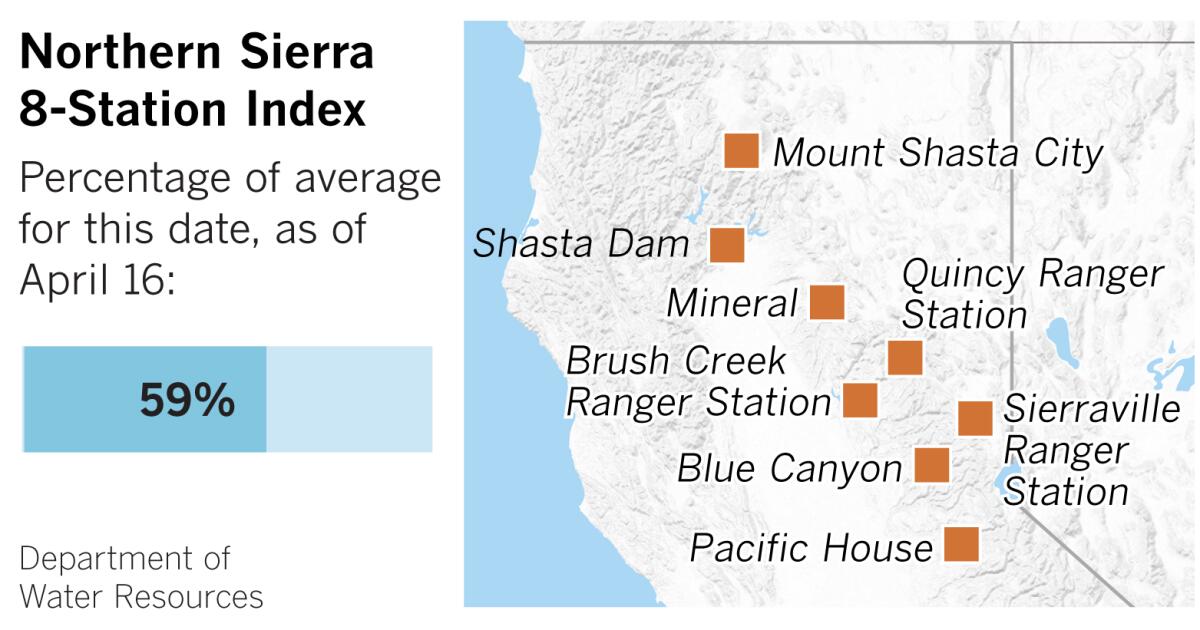

San Francisco, with 10.99 inches of rain to date, stands at 50% of normal. Sacramento is at 56% of normal, the city of Mount Shasta is at 46%, Ukiah is at 40%, and Montague in Siskiyou County is at 31%.

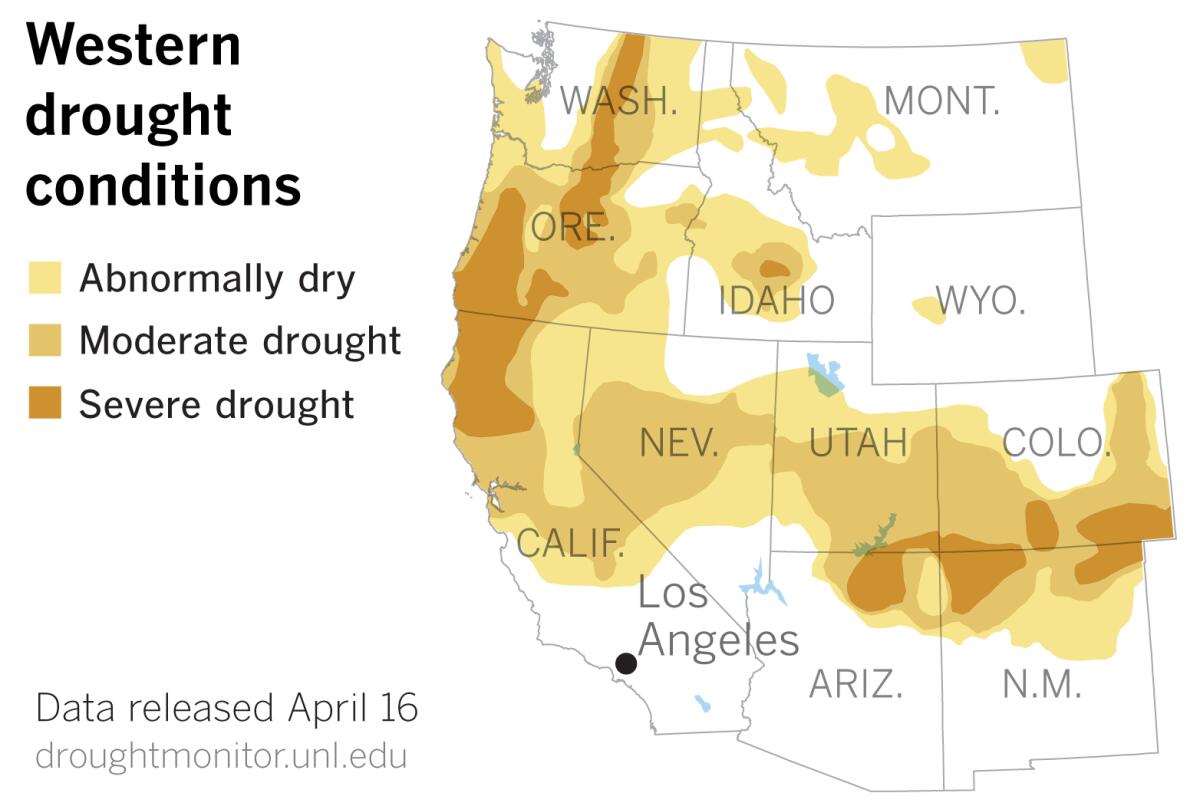

Though the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor data released Thursday show drought receding in Southern California, the northern part of the state is still beset by drought, as is much of the Western U.S.

Compared with drought data from a week ago, it is clear that an area of severe drought that had been hugging the California-Oregon border has expanded, plunging southward along the coast into Mendocino, Lake, Colusa and Butte counties.

The northern Sierra Nevada is mostly abnormally dry, and the Northern Sierra 8-Station Index is at 59% of seasonal normal, as of Thursday. The index is the average of eight precipitation measuring sites that provide a representative sample of the northern Sierra’s major watersheds. These watersheds include the Sacramento, Feather, Yuba and American rivers. These rivers flow into some of California’s biggest reservoirs, providing a large portion of the state’s water supply.

Based on this information, the idea of a looming drought becomes more plausible, even for Southern Californians tired of being cooped up at home while it pours outside.

The shift of the polar jet stream to the north this winter meant fewer Pacific storms slamming into Northern California and a skimpy snowpack in the Sierra. That has resulted in a drier year this year for much of the state than last year. That’s the picture in the short term, but the long-term pattern is also dry.

A new study from the Earth Institute at Columbia University calls the emerging long-term dry pattern in the Western U.S. a megadrought in which a warming climate is playing a key role. The megadrought is as bad as or worse than droughts known from prehistory, the study’s authors say, based on modern weather observations, 1,200 years of tree-ring data and dozens of climate models.

Based on tree rings, the researchers identified four megadroughts that lasted decades: in the late 800s, the mid-1100s, the 1200s and the late 1500s. The 19 years from 2000 to 2018 were compared with the worst 19-year segments of those historical droughts, and the current Western drought was judged to be outdoing the first three episodes. The fourth historical megadrought, from 1575 to 1603, was judged to be the worst. The difference between it and the current drought was slight and considered to be within the range of uncertainty. The current drought is more widespread and more consistent, which researchers attribute to global warming.

The megadrought in the 1200s lasted nearly a century. All of the ancient droughts lasted longer than 19 years, and they all began on a path similar to the modern drought.

According to the Columbia researchers, the 20th century emerges from the data as the wettest century in the 1,200 years of data. During that time, populations burgeoned along with overly optimistic assessments of the available water.

But Patzert, former climatologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says there have been many decades of punishing drought in the 20th century. He cites droughts such as the long one in the 1920s and ’30s known as the Dust Bowl, which affected the entire Western U.S.; a megadrought of 33 years from 1945 to 1978, which led to construction of the State Water Project in California; and the current drought, which he views as beginning in 1999 after a wet period in the 1980s and ’90s.

“If the 20th century is characterized as the wettest in the last 1,200 years, we’re living on some very dry, drought-prone real estate,” Patzert said.

Regardless, lengthy and stubborn droughts, even megadroughts, have clearly been looming over California and the West much more than many people realize. Reliable monsters such as these make you want to sleep with the lights on.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.