California ghost town with a bloody past suffers a new calamity

KEELER, Calif. — The smell of scorched wood and melted wiring lingered in the air Thursday as Brent Underwood surveyed the damage to this 19th century mining town perched 8,500 feet above the Owens Valley floor.

The marketer and his partners bought the Cerro Gordo ghost town for $1.4 million in 2018 with the goal of transforming it into a remote tourist attraction. Visitors would enjoy gourmet meals, hikes to scowling mine shafts and overnight stays in a rickety bunkhouse and hotel.

But that dream suffered a fiery setback last week. Underwood said he was awakened at 3 a.m. June 15 by the stuff of nightmares: furious winds driving flames that were leaping like demons and scorching unpredictable paths up slopes dotted with historic mining structures. Then came the explosions of propane tanks as flames engulfed the hotel.

In a cruel irony, Underwood said, “The American Hotel opened on June 15, 1871, and it burned to the ground 149 years to the day later on June 15, 2020.”

Asked Friday about the cause of the blaze, the Lone Pine Fire Department said only that it was still under investigation.

There is no running water in Cerro Gordo’s weathered collection of old mining equipment, junked cars and 22 structures, some of them with walls insulated with newspapers. “All I could do was call 911,” Underwood said. “And then, with help from a caretaker, I used buckets to desperately fling water from storage tanks onto the flames.”

After firefighters put out the last embers, three historic treasures had been reduced to ashes: an icehouse, a residence and the hotel.

“We may never know exactly what started this fire,” Underwood said from a balcony overlooking the charred ruins. “Fire officials told me that it could have been a thousand different things in these old buildings.”

Then, the lanky 32-year-old suggested the cause might be paranormal. “The caretaker here told me that he and another person saw a shadowy apparition moving in the hotel kitchen at 4 p.m. the previous day.”

Strange occurrences and ghostly apparitions are part of the myth and allure that Underwood and his partners are banking on, in part, to create a wilderness hideaway like no other for urbanites aching to escape the clatter and routine of city life.

Should Inyo County rename a campground that has a derogatory name? A lawyer has made that his mission, angering many longtime residents of Lone Pine.

Their supporters include Terri Geissinger, a historian of the West. “Cerro Gordo is a nugget in time that needs to be preserved,” she said. “But maintaining a ghost town is only for the roughest and toughest of people. That’s because you’re going to get frustrated, beat up and kicked in the gut.

“You can’t do it with just money,” she added. “It’s takes a heart of steel.”

Located on roughly 400 acres in the Inyo Mountains, Cerro Gordo was not designed for comfort.

In its heyday, there was a murder a week in Cerro Gordo, an extraordinarily violent community of about 500 people. Silver miners slept on cots surrounded by sandbags stacked 4 feet high to protect themselves from stray bullets. In the late 1800s, an estimated 30 miners who had emigrated from China were buried in a mine shaft.

The house that was destroyed by fire on Monday once belonged to a man named William Crapo, who gunned down a postmaster as he walked along the dirt road skirting the American Hotel.

A fundraiser organized by the nonprofit Friends of Cerro Gordo has already collected more than $17,000 that will be used to rebuild the hotel to current construction and safety codes.

“The loss of the American Hotel is incalculable,” said Roger Vargo, president of Friends of Cerro Gordo, “due to its historic value to the growth of Los Angeles and much of the Old West.”

“Only a week ago,” he added, “it commanded the center of town on a mountain with views of Owens Valley and the eastern Sierra Nevada to the west and Death Valley to the east.”

A year ago, the hotel and other Cerro Gordo structures were explored in an episode of the TV show “Ghost Adventures” that focused on two children who died after being trapped in a steamer trunk.

Underwood’s commitment to the Cerro Gordo restoration project has been tested mightily in recent months.

The mean comments on social media platforms started the moment Cerro Gordo was sold. Underwood was vilified as a trust-funder who took over the mining town as some sort of hobby.

“That hurt a little bit,” said Underwood, the son of schoolteachers who was born and raised in Tampa, Fla.

Shortly after he decided to wait out the coronavirus lockdown in Cerro Gordo, the area was buried in 5 feet of snow.

“There was no way in or out for several weeks,” he said. (The only way to get to the mining town is via a 7½-mile steep, gravel road.) “After the snow melted, I was hospitalized with a bad case of appendicitis.”

Judging from historical records, the original residents of Cerro Gordo may not have been sympathetic.

The town’s name translates from Spanish into “Fat Hill,” and 150 years ago it was the home of silver miners who shipped their diggings off to the small pueblo of Los Angeles by 20-mule team or by steamboats that navigated the once-full Owens Lake.

Life was short and hard in the area, which produced 4.5 million ounces of silver before declining precious-metal prices sank the local economy, save for a zinc revival from 1911 to 1919.

Today, only a small fraction of the town’s original 500 structures still stand. They include a general store, an assayer’s office, the well-preserved mining operation up on a hill and the remains of a brothel once known as Lola’s Palace of Pleasure.

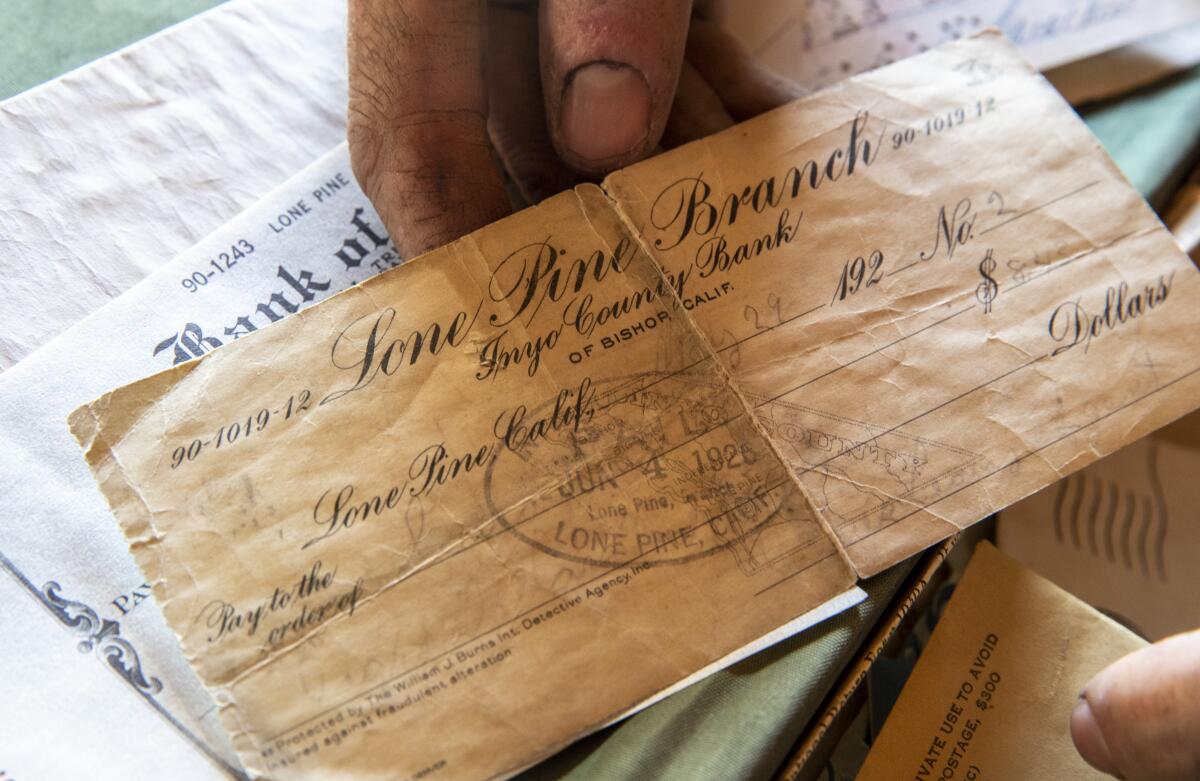

The outdoor plumbing consists of unheated and unlighted Old West outhouses. The ground bristles with artifacts: rusty pocket watches, iron tools, shattered window glass and whiskey bottles.

“The fire was heartbreaking, because I have a deep emotional attachment to this place,” Underwood said. “But we’re not giving up.”

“Truth be told,” he added, “we’ve got big plans for little Cerro Gordo.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.